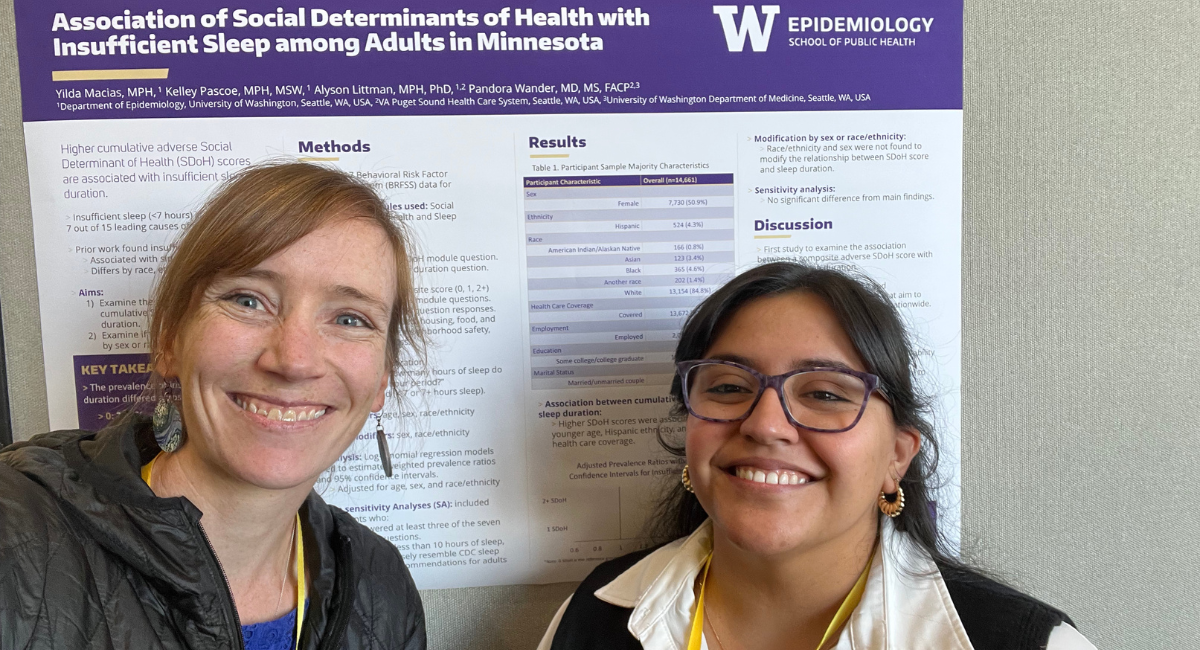

Yilda Macias was named a 2025-26 Magnuson Scholar, which will support her research of PCOS and chronic health conditions (Photo courtesy Yilda Macias).

When Yilda Macias was growing up in Texas, she noticed certain health problems affected some communities more than others. Diseases like diabetes or cancer often impacted family and friends in her Hispanic community, and many of them would travel to Mexico for healthcare because treatment was more affordable than in the U.S.

It wasn’t until she was earning a Master of Public Health in New Mexico that she started to understand why these disparities existed. At New Mexico State University, she worked with a team studying cancer health disparities between people living in border towns in Texas and those living in larger cities. She saw that circumstances like where people lived, what food they ate, and what health care they had access to impacted health conditions throughout their lives.

This was Macias’s introduction to public health, and she has been studying health disparities since. Now an Epidemiology doctoral candidate at the University of Washington School of Public Health, she leads research on the connection between PCOS – Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – and other health conditions like diabetes and cancer. She was recently named a 2025-26 Magnuson Scholar, which awards funding to academically excellent students in the UW health sciences schools who demonstrate an outstanding potential for health sciences research. The scholarship honors the late Senator Warren G. Magnuson’s commitment to improving the nation’s health through biomedical discoveries.

“I hope to use my PhD to lead research that I feel genuinely makes a difference in how we detect PCOS, how we understand it, and especially how we address it in communities that haven't always been included in research,” Macias said.

Macias first became interested in studying PCOS after learning that many close friends and family members were living with the condition. PCOS is a common hormone disorder that affects 5 to 6 million people in the U.S., yet it has not been the focus of much epidemiological research, Macias said. PCOS is often associated with infertility due to irregular ovulation, but symptoms vary widely, including acne, hair growth, hair loss, weight gain, insulin resistance, or growths on ovaries.

Because the symptoms are so different, PCOS often goes undiagnosed. This is a problem because PCOS has been linked to serious conditions like heart disease, sleep apnea, and type two diabetes. More than half of individuals with PCOS develop type 2 diabetes by the age of 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the connection between PCOS and other diseases like diabetes can help people address their risk for and potentially prevent serious health conditions.

Health disparities can lead to delays in treatment, which in turn can then exacerbate the impacts of PCOS, Macias said. People with PCOS who don’t have access to health care – whether they are uninsured or geographically far from health providers – may be less likely to receive a diagnosis, and therefore, care. Many insurance companies also require patients to obtain a referral before pursuing treatment, which can add additional costs and further delay care.

“Tackling PCOS becomes an issue of reproductive justice and chronic disease prevention at the population level,” Macias said.

Macias’s dissertation explores the connection between PCOS and other diseases like diabetes and pancreatic cancer, which is highly fatal; only about 10% of those who are diagnosed survive more than 5 years. Right now, it is unknown exactly how these conditions may be connected, but they do share common hallmarks, including obesity, chronic inflammation, and insulin resistance. Macias is also researching the factors that contribute to the underdiagnosis and underrepresentation of PCOS in large population-based studies. She hopes this research will lead to better access to diagnosis, treatment, and long-term care.

“It’s very common for people with PCOS to have feelings of being dismissed or not heard by their doctors,” Macias said. “Looking at the impacts of those feelings is very important, because it's not just frustrating for the person, it can actually have real negative consequences down the line for their health.”

Her research also looks at the role hormones, genetics, and metabolic factors play in PCOS and chronic disease. Her dissertation will incorporate observational and genetic data from large cohorts and biobanks around the world to better understand how PCOS is linked to the development of pancreatic cancer later in life. Macias also plans to simulate potential outcomes under different exposure scenarios, closely mimicking a randomized-controlled trial, to get a better understanding of the individual and joint impacts of PCOS and obesity on the development of type 2 diabetes.

Macias wants to use the rigorous research methods she is learning from her training as an epidemiology doctoral candidate to answer questions about how PCOS impacts an individual’s long-term health outcomes. In the future, she hopes the research she publishes will impact interventions and policy that can improve health for people with PCOS and chronic diseases. Macias said she chose to study at the UW School of Public Health because of the rigor of the epidemiology and biostatistics courses, the ability to collaborate with faculty and research partners — like the Fred Hutch Cancer Center — and the School’s commitment to addressing health inequities.

“I was confident that if I came to the UW School of Public Health, I was going to receive training and mentorship to provide that strong foundation that I would need,” she said.

Macias’s long-term goal is to lead research with a large interdisciplinary team of researchers, medical practitioners, and patients from diverse groups to study these gaps in understanding PCOS across the life course and in diverse populations. Including patients from a wide range of racial, ethnic, and gender backgrounds in research can help uncover how health disparities — including the ones she first noticed growing up in Texas — play a role in someone’s diagnosis of PCOS, their quality of life, and their long-term health outcomes, Macias said.

“Historical underfunding of reproductive health research and women's health has created significant gaps in our knowledge of PCOS,” Macias said. “One of the most rewarding things is hearing about people with PCOS feeling like research is finally starting to take them seriously.”