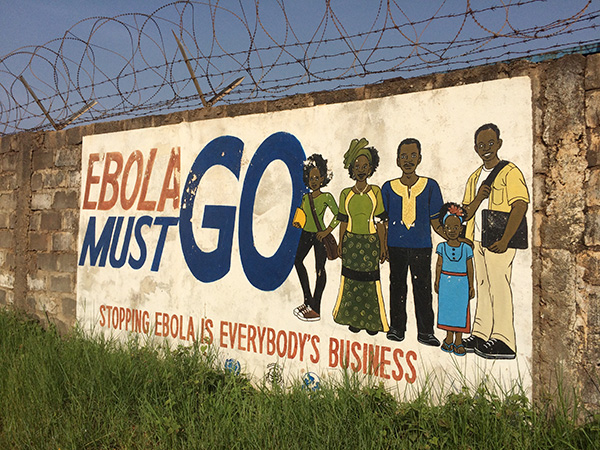

The 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa rapidly became the deadliest occurrence of the disease — claiming 4,809 lives in Liberia alone. Now new research from the University of Washington suggests Ebola's collateral effects on that nation's health system likely caused more deaths than Ebola did directly.

The study, published Feb. 20 in PLOS Medicine, found that it only took four months for Liberia to lose between 35 percent and 67 percent of primary health care services after the Ebola outbreak began.

“People were unable to receive essential primary care during and immediately after the epidemic,” said Bradley Wagenaar, the study’s lead author. “Pregnant women weren’t getting essential antenatal care. Those in labor weren’t going to the clinic to give birth but were instead birthing at home.”

Also, people infected with malaria weren’t receiving essential drugs and children weren’t being vaccinated against preventable diseases, he added. Wagenaar is an acting assistant professor in the UW’s Department of Global Health, which bridges the schools of Public Health and Medicine.

Using data from 379 health clinics across Liberia, a country severely affected by the Ebola outbreak, researchers measured the delivery of primary healthcare during and immediately after the outbreak. They also assessed output as health systems recovered in the following two years.

Wagenaar and research colleagues estimate that Ebola in Liberia led to a loss of about 776,000 primary healthcare visits, based on typical patient-visit volumes. Additionally, they estimated nearly 25,000 fewer tuberculosis vaccinations for kids, 5,000-fewer attended births, and more than 100,000 fewer treatments for malaria.

Liberia's malaria cases have increased by 50 percent since the outbreak, compared with pre-Ebola levels. The investigators hypothesize that this increase might stem from the disruption of malaria treatments and other preventive measures such as bed net distribution. They also found that it look 19 months after the last case of Ebola was discharged for 10 primary healthcare indicators to recover to pre-Ebola levels.

“Once the Ebola outbreak ended, the sad truth is that most of the money earmarked for health systems improvement in Liberia disappeared,” Wagenaar said. The researchers suggest that significant funding must be allocated to maintain public-sector primary healthcare delivery during future public-health emergencies.

“We know that the Ebola outbreak wasn’t a random occurrence in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia,” Wagenaar said. These countries suffer from underfunded health systems due to decades of structural adjustment, unfair debt repayments and continued austerity in funding public-sector health and education systems.

“It’s high time that the international community invests in Ministries of Health to build resilient public-sector primary healthcare systems capable of mitigating collateral effects of the next emerging epidemic – and ideally preventing the spread of the next international pandemic.”