SPH researchers seek to reduce deaths and injuries

When he moved to the U.S. from Iran in 2003, Ali Rowhani-Rahbar was peppered with questions from his new acquaintances about culture shock.

A young medical doctor pursuing his master’s in public health, Rowhani-Rahbar would tell them the U.S. was a wonderful place for personal and professional growth, with an exciting multicultural environment and new freedoms. But he was shocked by the extent of gun violence.

“Every day in this country, 90 people die due to firearm injuries and more than 200 people get shot,” said Rowhani-Rahbar (PhD Epidemiology 2009), now an assistant professor of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health.

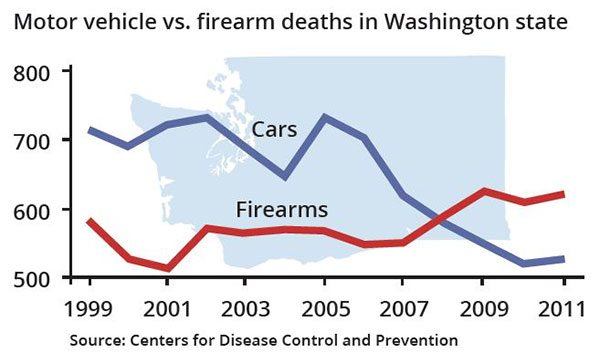

The more he looked at the numbers, the more incredulous he became. Total deaths by guns in the U.S. are about 33,000 a year—rivaling the number of Americans killed by automobiles.

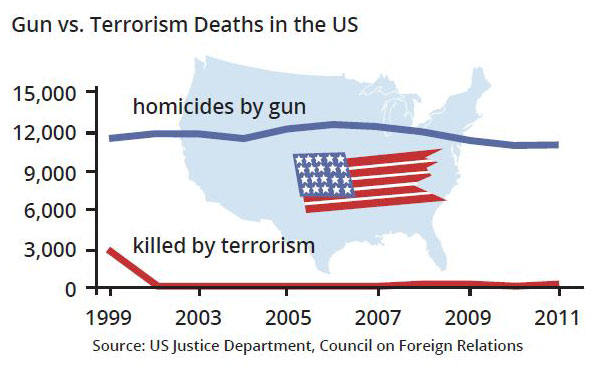

“More Americans have died due to a firearm injury since 1968 than on the battlefields of all the wars in American history,” he notes. “The frequency of these shootings has made us a little numb.”

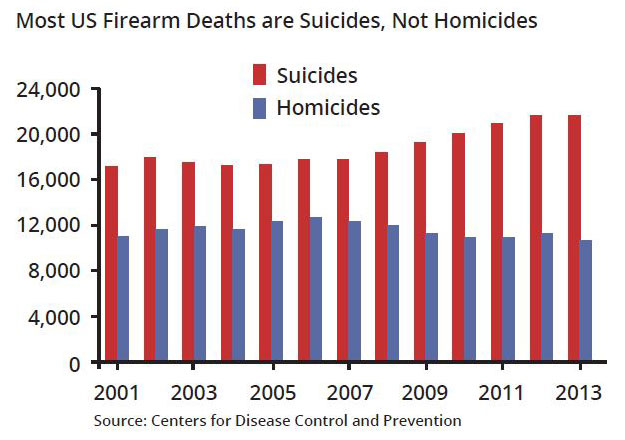

These days, Rowhani-Rahbar is one of the small but growing number of researchers examining the nature of gun violence—or, as he prefers to describe it, firearm injuries. (Gun violence connotes mass shootings and gang violence, which are major problems, he says, but doesn’t bring to mind suicides, which account for about two-thirds of all gun-related deaths.)

“It was really Sandy Hook that connected me to these research efforts,” he says. The massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newton, CT, in 2012 claimed 27 lives, most of them young children.

After that shooting, Frederick Rivara (MPH 1980), professor of Pediatrics and adjunct professor of Epidemiology, asked Rowhani-Rahbar if he would take part in a research project on gun violence funded by the Seattle City Council. Rivara was a pioneering gun violence researcher, along with SPH alumnus Arthur Kellerman (MPH Health Services 1985), until the mid-1990s, when Congress essentially eliminated federal funding for gun research.

The city, seeking a new kind of partnership, approached the UW’s Harborview Injury and Prevention Research Center, where Rivara and Rowhani-Rahbar are core faculty members.

Using epidemiologic methods, the researchers began to track gun violence as if it were a disease. They looked at hospital and arrest records from across Washington state, identifying nearly 700 trauma patients who had sustained a firearm injury over a two-year period. They found that people who had been shot by a gun and survived were dramatically more likely to be re-injured or killed by a gun—and to commit a future crime.

The study also found that those with a criminal history of arrest were much more likely to commit violent crime than those who were diagnosed with a mental illness.

Now researchers want to know how to protect those who have been shot from harming themselves or others in the future. “The next obvious step would be to do an intervention,” Rowhani-Rahbar says.

With a new, $275,000 grant from the City of Seattle, researchers plan to conduct a three-year randomized trial for gunshot victims at Harborview Medical Center. Half of the patients would receive usual care, which includes social-work support and a list of community services.

The other half would get a three-part intervention:

- “Motivational interviewing,” a technique involving conversations with patients to understand the intentions behind their actions. The idea is to motivate them to change their behavior.

- “Extended community outreach,” linking patients with services such as substance abuse or mental health treatment, education and employment opportunities, and housing. A menu of options is tailored to the person’s needs. For six months, patients will be assigned a case manager who will stay in frequent contact.

- A multidisciplinary team of “stakeholders”—those in charge of various community services—who will meet to discuss each case to see if they can provide further support.

“When they get out of the hospital, it might be very hard for them to navigate life after a traumatic event such as getting shot,” Rowhani-Rahbar says. “We understand things like retaliation. It’s a critical transition time.”

Patients would be followed for a year to see if they get injured again, die, or commit a crime. Mental health status, employment, and other outcomes would be recorded. Researchers hope to enroll about 200 patients over a two-year period.

Similar programs are run by the National Network of Hospital-based Violence Intervention programs in certain hospitals. “What we need is evidence that it works,” Rowhani-Rahbar says.

Because of the lack of funding, many questions about gun violence have gone unanswered.

“From the public health perspective, we need to collect data,” Rowhani-Rahbar says. “Data can tell us the magnitude or size or the problem, as well as the pattern of the problem, and that’s how you make policy decisions, with informed choice. That’s exactly what we’ve done for car collisions. We’ve made great progress. Same for smoking and tobacco. These are examples of success and triumph for public health. Here, we can do the same.”

Two graduate students in Epidemiology—Vivian Lyons and Anton Quist—have been researching the kinds of data sets available about firearm injuries. Another student, Brianna Mills, took part in the study tracking Washington state gun victims and is conducting her dissertation on this topic.

“We need the ability to conduct gun research but Congress still refuses to fund the CDC’s efforts to conduct such research,” Frederick Rivara said.

In addition to research, Rowhani-Rahbar, Rivara, and Mary D. Fan, a professor of law who’s pursuing a PhD in epidemiology, are writing a book tentatively titled, “Guns in the Family.”

“The book challenges the romanticized ideal of having guns in the home in defense of family,” Fan says. “It’s about the safety regulations that communities seeking to reduce firearms-related injuries and death can adopt without running afoul of the increasingly muscular Second Amendment.”

Rivara says research shows that keeping a gun in the home increases the risk of violent death from homicide or suicide.

SPH researchers are also focusing on the effectiveness of interventions designed to provide safe firearms storage.

“For those who do own guns, what can we do to make sure that we are adhering to the highest level of safety?” Rowhani-Rahbar asks. “How can we promote safe gun storage? We do have evidence that loaded and unlocked guns increase the risk for suicide among teens.”

He stresses research is not about taking guns away from people, but about saving lives.

Rowhani-Rahbar cites the legendary epidemiologist William Foege, who helped devise the strategy to wipe out smallpox. Foege always tells people to “work on important things,” Rowhani-Rahbar notes. “Firearm injuries are a really important public health problem in our country. And we need money to research it. To me, if it could save one life, that’s a huge accomplishment.”

A new Gun Responsibility and Injury Prevention Research Fund has been established by a generous donor to support Rowhani-Rahbar’s research. To contribute, contact sphadv@uw.edu.