Why? Why? Why?

Hundreds of University of Washington Health Sciences students were encouraged to keep asking the "why" question last week during the fourth and final session of a year-long Interprofessional Education Initiative (IPE) program.

The topic was pediatric dental caries, or tooth decay, a major public health problem. The exercise was part of an effort to get professional students to consider the root causes of a larger health issue rather than focusing solely on the individual patient.

The lesson plan for the final session was inspired by two lessons from a health equity curriculum designed by Linn Gould, Executive Director of the non-profit Just Health Action and a clinical instructor in the Department of Health Services in the UW School of Public Health.

About 75 faculty members -- in teams of two -- led small discussion groups of 12 to 16 students, which in turn were broken up into smaller groups.

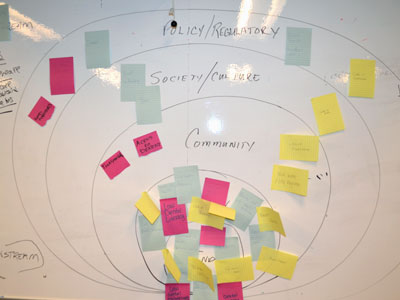

The point of the discussions, Gould said, was that many people, including doctors, "blame the victim" for not changing his or her behavior around smoking, drinking or eating unhealthy food, when often their behavior is outside of their control due to social, political, economic or environmental factors.

"For example, with dental caries, it's very easy to blame someone for having lots of dental caries without acknowledging that they might not be able to afford a tooth brush or have access to affordable, healthy food," Gould said.

"We then encourage students to think about 'upstream' solutions beyond just providing people with tooth brushes. For example, in my session, one student group said 'stop vending machines at schools with candy and soda' and another group said 'provide transportation for people to get to dentists in rural areas or have mobile dentists vans.'"

In another group, students suggested a range of reasons for dental caries, from low dental literacy to lack of fluoridation. Subsidies to farmers to grow corn were also cited. High-fructose corn syrup makes its way into thousands of processed foods as a substitute for sugar, but is just as bad for teeth, researchers say.

Earlier, Dental students made the case in their respective discussion groups why dental caries is a public health problem, while Nursing students shared key points from their recent community health rotations.

Stephen Bezruchka, senior lecturer of Health Services and Global Health, said students were engaged and collaborative in the group he helped facilitate. "They all seemed to learn from each other," he said, adding it was a good opportunity to highlight health disparities in society.

About 650 students from the six Health Sciences Schools – including 12 from the Nutritional Sciences program within the School of Public Health, physician assistants, and students from Medicine, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Nursing and Social Work – are taking part in the IPE.

Previous sessions included a case study about a patient who suffered heart failure who didn't want medical treatment; a session on veterans and health care; and discussion on error disclosure.

"It really helps students understand what other professions are capable of doing and what their skillsets are," said Michelle Averill, acting assistant professor of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences and coordinator of the IPE program for the School of Public Health. Averill and the IPE planning team developed Gould's ideas into an 11-page guide for the training session.

"A long standing interest of mine is understanding the true barriers that patients have to optimal disease prevention and management, and acknowledging what barriers exist outside of the scope of primary care practice that require public health/policy intervention," Averill said. "I was very excited to combine my interests with the IPE mission to promote interdisciplinary communication."

Katherine Getts, a graduate student in Public Health Nutrition, said the IPE program was one of the highlights of her clinical training.

"It was wonderful to collaborate with other allied health students and learn about the different knowledge base and perspectives that each profession brings to the table," Getts said. "It elucidated for me both the unique role my own profession has in health care and how Registered Dietitians can work closely with other providers to provide patient-centered care."

Elizabeth Hulbrock, another Public Health Nutrition student, said the IPE strengthened her ability to apply individual skills in a team care setting that emphasized the unique contributions of each member. "I was able to explore my own role in the healthcare team while improving interprofessional communication skills," she said.