Students learn by doing at UW School of Public Health

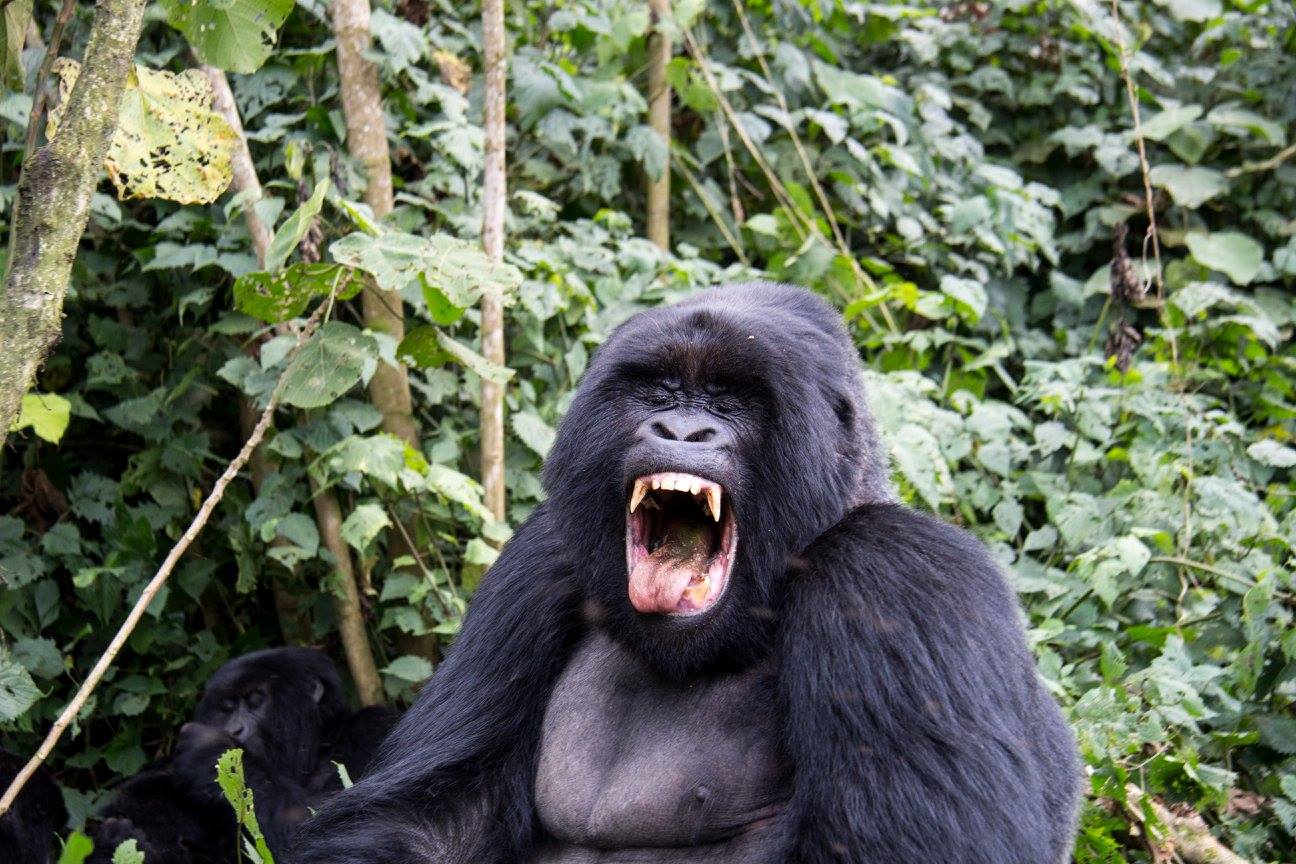

Erica Grant climbed the steep lava slopes of Rwanda’s volcanic park and trekked through its dense rain forest to see some of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas. What surprised her most wasn’t so much the great apes themselves, but how difficult it was for tourists to keep a safe distance away.

Ecotourism, while important for local economies and conservation efforts, is making it hard to protect gorillas from dangerous zoonotic diseases that spread between animals and humans. One deadly downside for gorillas: respiratory infections from human viruses.

This was an ideal setting for Grant when she was an MPH student in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health. She studied One Health, an approach that recognizes the multi-directional health linkages of humans, animals and the environment.

Grant is among thousands of SPH students who have gained valuable skills through life-changing experiences in the field. In Rwanda, she built a system for tracking data on the health of hundreds of guides, trackers and porters, so researchers could better understand how to prevent the spread of pathogens between humans and gorillas.

The idea that the most transferable and marketable skills are forged in real-world settings is at the core of the School’s strategy for experiential learning. In its simplest form, it means learning by doing. Research has shown that participation in activities outside of the classroom enriches the student experience – helping them connect their education to the larger world.

“I value classroom learning, but there’s only so much you can learn in an artificial environment,” says Grant, who graduated in 2018. “At some point, you have to get your boots dirty to really grow.”

She worked with the Gorilla Doctors, a team that cares for gorillas in the cloud forests of East Africa and whose efforts helped bring the critically endangered species back from the brink of extinction. One such initiative, an employee health program, provides annual health screenings and vaccinations for diseases like tuberculosis and measles, which can spread between humans and gorillas. Grant’s project, her practicum, was to develop an electronic database to store employee health data collected from park workers throughout the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Rwanda. She also integrated human and gorilla health databases to more effectively detect health trends.

“This could have been done over Skype, but my understanding of the project and how best to meet the needs would have been severely impaired,” Grant says. “This practicum was a powerful experience that opened my eyes to the challenges of implementing a One Health approach.”

Required by all MPH students at the School, the practicum integrates classroom learning with professional experience – cultivating skills such as grant writing, data analysis, program evaluation and policy development. It also matches students’ interests with the MPH core competencies. Students complete at least 120 hours of fieldwork with a health-related organization, and reflect on the practice experience and their greater contribution to the public health profession.

“Nothing beats getting your boots on the ground, working side by side with field experts to solve public health problems in unfamiliar environments,” says Janice North, experiential learning manager at SPH.

Students have worked with the Urban Indian Health Institute to study the availability of fruits and vegetables in Native American communities; partnered with the Washington State Department of Health to help cities and counties influence tobacco policy; designed videos and brochures explaining the signs of stroke for culturally diverse groups; and assessed gaps in health care for transgender youth.

Priyanka Gautom (BA ‘15) recently traveled to Washington, D.C., with watchdog group Hanford Challenge to influence legislation that affects the Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington state, one of the most contaminated sites in the U.S. Another student is working to build a health justice movement in Palestinian refugee camps.

About 200 students complete their practica every year. Orientations are now split up into small, interdisciplinary cohorts. Students present final projects during a symposium in the spring.

Another form of experiential learning is through capstone projects, a culminating experience for students nearing the end of their studies. A capstone course is part of the core curriculum for the recently renamed Public Health– Global Health major. Over two quarters, seniors draw upon knowledge they gain through coursework as they serve populations in a community-based, public health setting – a concept called service learning.

About 250 students in the major take part in the capstone every year, performing at least 12,000 collective hours of service at more than 26 organizations across Seattle. Organizations have included ROOTS Young Adult Shelter, Ballard Senior Center, Cherry Street Food Bank, Recovery Café and El Centro de la Raza.

“Students are fulfilling the needs, while also being thoughtful about the structures that create inequities they see and thinking critically about ways to change them,” says Sara Mackenzie (MPH ’05), director of the liberal education major. “This has been shown to increase civic engagement.”

The UW’s Carlson Center matches students to local organizations, where they are often exposed to new circumstances and communities. The goal is that students’ experiences will put context to the public health issues they are learning about in the classroom.

“They can read the literature, but it’s being there and hearing people’s stories that will help students to think differently about issues and ask different questions,” said Senior Lecturer Anjulie Ganti. She guides students as they reflect upon their service experience and studies to assess community needs and to gain a deeper understanding of public health.

Senior Ivanna de Anda served at the Elizabeth Gregory Home, a day center for homeless women in the University District. She washed dishes, distributed clothing, cooked and cleaned showers. She also built relationships with visitors, including women who identify as transgender, a vulnerable group that experiences some of the worst rates of homelessness, drug use and domestic violence.

“I have many friends who are trans, so this is very close to my heart,” says de Anda, originally from El Paso, and raised in Seattle. “Without having those one-on-one interactions, hearing their stories and discussing their specific needs, it’s hard to address the issues they face.”

Team-based capstones are also part of the new Food Systems, Nutrition and Health major, housed in the Nutritional Sciences Program, which enrolled its first 29 students in January, and the Health Informatics and Health Information Management program. The Environmental Health major has an internship requirement. All undergraduates are invited to present their final projects at a symposium in the spring.

Other forms of experiential learning include First- Year Interest Groups, undergraduate research, study abroad, independent studies and clinical rotations. These experiences reshape the landscape of learning and help students like Grant and de Anda to launch their careers. Grant applied her training as a One Health researcher in Uganda, studying microbial transmission among humans, animals and environmental reservoirs. She is now pursuing a PhD in Luxembourg. Today de Anda is a paid employee at the Elizabeth Gregory Home.

Says Dean Hilary Godwin: “We’re continuing to explore how to create high-impact learning experiences inside and outside of the classroom – both in the School and across the UW. Nothing beats tackling challenges in field and practicum settings to create transformative experiences. This is especially true for public health students who want to change the world.”