New book outlines problem-based learning techniques

As a master’s student in the Community-Oriented Public Health Practice (COPHP) program at the University of Washington School of Public Health, Genya Shimkin had an idea for a pocket-sized card that could help LGBTQ youth feel safer in health care settings.

Shimkin developed and tested a version of what was dubbed the Q Card for a final capstone project, which COPHP students complete in collaboration with client organizations. The folding cards have space for youth to fill in their name, gender identity, sexual orientation and pronoun, plus a tear-off panel for health care providers with tips on providing sensitive care to queer and trans youth. Since graduating in 2013, Shimkin has continued to build the Q Card Project, distributing 125,000 little pink cards in three languages to youth, schools, libraries, community organizations and others who interact with LGBTQ young people.

Shimkin attributes much of the Q Card’s success to the skills and contacts gained through the COPHP program.

"The greatest gift that COPHP gave a lot of us was a sort of a fearlessness,” Shimkin said. “COPHP said, ‘Hop in and learn how to do it.’”

Learning by doing is a central tenant of COPHP. More formally, the program’s teaching approach is called “problem-based learning.” Rooted in adult learning theory, problem-based learning requires students to actively engage in solving real problems.

Now COPHP faculty have published a book to help other schools of public health incorporate the problem-based learning model that COPHP has refined over 16 years.

“Experiential Teaching for Public Health Practice: Using Cases in Problem-Based Learning,” edited by Bud Nicola and Amy Hagopian, details the elements of a successful problem-based learning program and shows how the techniques can be used to teach core curricular content. The book, available for free download from Bentham eBooks, also includes extensive appendices to help implement this unique way of teaching.

“It's very difficult to move from a lecture-based model into something that's very active like problem-based learning,” said Nicola, an affiliate professor in the Department of Health Services who helped design the COPHP program. “It takes a lot of courage, and it takes some guidance. This book provides the guidance."

COPHP was originally coached by faculty at Drexel University’s School of Public Health, who were pioneers of problem-based learning in U.S. public health education for graduate students. Some medical and business schools and K–12 institutions also use the approach.

"We’d really like other schools to try this, and not just in public health,” said Amy Hagopian, associate professor of Health Services and Global Health, and director of the COPHP program. “We think higher education should be moving in this direction."

What sets COPHP apart from other public health programs is that students work on “real projects that have real deliverables for real clients,” Hagopian said. “So they learn all the weirdness of working with clients who might be unclear about what they really want or vague on various aspects of their project.”

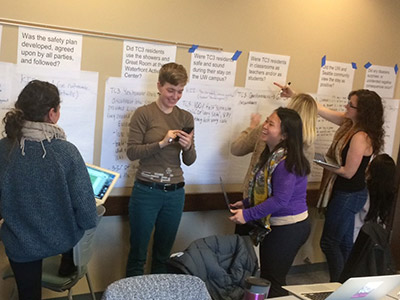

Students work together in small groups to design the steps needed to navigate the problems posed in the cases, which include both hypothetical examples drawn from actual public health situations and real projects for agencies and community groups. Students take turns facilitating the groups, so that they build essential skills working in and leading groups, and in interpersonal communications. Faculty mainly provide coaching and feedback, and strive to “keep their mouth shut while the students struggle,” Nicola said.

Such team-based problem-solving mimics how workplaces operate, said COPHP alumna Hilary Heishman (MPH, 07). Faculty “don’t give you that much information — you have to figure it out and draw in expertise from various sources,” said Heishman, now a senior program officer with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “And that completely matches my life in all my roles since then."

"COPHP really prepared me for real-world work in public health,” Heishman said, “and not only public health, because what it taught us was skills and a way of thinking that are widely applicable."

For second-year COPHP student Francesca Collins, completing projects for client organizations helped her develop skills she didn’t know she was capable of — and with them, new confidence in her abilities. "I've done so many things I never imagined I would do," she said.

For her capstone, Collins researched and developed an intrauterine device self-removal guide with the UW’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Family Planning. "I never thought of myself as a strong math and science person until I was able to accomplish some challenging projects in this program that were beyond my experience level and comfort zone,” Collins said. “It opened doors that I wasn't expecting."

COPHP faculty members Nicola and Hagopian realize that most schools of public health are unlikely to make a wholesale switch to problem-based learning, but their book offers ideas for incorporating cases, problems and projects into existing programs. The payoff, they say, is highly prepared and in-demand graduates. Of recent COPHP graduates, 94 percent are working full-time in public health jobs.

“If other schools want graduates who are fully confident in their ability to do a new job, who feel great about the training they’ve had and are willing to do anything to support the program afterwards,” they should consider adopting problem-based learning, Nicola said.

“Experiential Teaching for Public Health Practice” can be downloaded for free, and printed copies can also be purchased from publisher Bentham eBooks.

Book contributors include faculty from COPHP, the University of Washington Medical Center and Evans School of Public Policy and Governance, and the Washington State Health Care Authority.

(By Allegra Abramo for the School of Public Health)