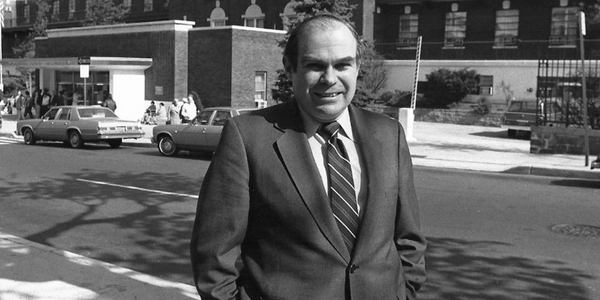

The public health community is mourning the loss of Victor Sidel, former president of the American Public Health Association and a founding member of Physicians for Social Responsibility. Dr. Sidel taught social medicine and inspired students to see health problems in a socioeconomic context. Stephen Bezruchka, senior lecturer of health services and global health, was one of the many public health scientists inspired by his former mentor.

“Victor Sidel had a profound impact on social epidemiology and social medicine not only in the U.S. but far afield,” Bezruchka recalled. “I first encountered him as a student at Stanford Junior Medical School in 1971 after he and his wife, Ruth, had returned from China. This was back in the days when there was a huge blackout on the country.

“Along with Joshua Horn, a British surgeon who worked there, and who also visited around the same time, I learned of Chinese barefoot doctors. I had a chance to emulate this concept in Nepal a few years later.

“Then I would hear Vic’s talks, which always had props to draw attention to critical issues. For example, to depict bomb deaths, he would have a can of BBs and drop them one at a time into another metal container making a clashing sound. The rate would increase as he talked and by the time he got to the actual rates, they would fall fast.

“I’ve never found anyone else who could use such props to make a point the way Victor Sidel did. I later invited him to speak at various events, where he made great impacts in critical thinking.”

Bezruchka shared the following eulogy given by Barry Levy.

Vic Sidel: A Remembrance

Less than two years after the death of Ruth, we are again gathered together, this time to mourn the passing of Vic; to acknowledge his contributions to health, peace, and social justice; and to honor him - not only for what he did, but also for the person he was.

Vic made enormous contributions to public health and social medicine. For 5 years, he directed the Community Health Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, and for 16 years, he directed the Department of Social Medicine at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine. To Vic, social medicine promoted health and prevented disease in the community. And it also increased social well-being by improving housing, nutrition, education, and employment opportunities and by combating racism, discriminatory practices, and inequities in health care.

Vic taught social medicine, in part, by placing students in the community and enabling them to witness patients' health problems in a socioeconomic context, to recognize what we now call the social determinants of health, and to identify community resources to address patients' health problems.

Vic recognized that community-based problems require community-based solutions. So he trained community health workers to promote health and prevent disease in the neighborhoods where they lived. These workers were very proud of their role; one of them, in fact, was so proud that she wanted to be buried in her uniform.

Vic saw health as a basic human right. He lamented that much medical care in the United States was becoming corporatized and monetized, that medical care was increasingly seen as a commodity and an opportunity for profit. Vic recognized that government is responsible for both equitable financing and equitable provision of health care, and so he strongly supported a national health program and served on the board of Physicians for a National Health Program.

Vic advocated for peace. He resisted militarism and he resisted the diversion of resources for military purposes. He opposed easy access to guns and assault weapons that ultimately lead to domestic and community violence, and he opposed international arms sales that ultimately lead to war.

In 1961, Vic co-founded Physicians for Social Responsibility to raise awareness of the threat of nuclear weapons - what he called "the final epidemic." And he inspired physicians and medical students across the country to establish local PSR chapters. In the early 1980s, he helped establish the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Vic served as president of PSR and co-president of IPPNW. He was in Oslo in 1985 to help celebrate IPPNW's receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize. And Vic actively supported many other activities to promote peace, including those of the APHA Peace Caucus.

As a Princeton-trained physicist, Vic appreciated the importance of statistics, and he used statistics to document the impacts of militarism and war. But he reminded us that statistics are actually people with the tears washed off. Vic envisioned a culture of peace, where conflicts are settled without violence and where the dignity of every person is respected.

Vic promoted social justice. He recognized that the denial of human rights adversely affects health. He strongly supported a woman's right to choose. He supported a person's right to die with dignity. And he enlightened us on the linkages among health, human rights, and civil liberties, and among social justice, environmental justice, and justice in the workplace. As president of the American Public Health Association and the Public Health Association of New York City, Vic addressed the growing gaps between the rich and the poor people in the United States and between rich and poor countries.

Vic taught us that health, peace, and social justice were not isolated concepts, but tightly woven together. I can still hear him saying there cannot be health without peace and social justice, and there cannot be peace and social justice without health.

Vic – and Ruth – were leaders and innovators in many ways. In 1971, they were among the first Americans to visit the People's Republic of China in 22 years. Their subsequent books and lectures enlightened us about health and social services in China. They wrote and spoke about its key principles, including: Put prevention first. Train community members as "barefoot doctors" to provide health services in underserved areas. And base the health system on the concept "Serve the people," in which the gratification of health workers comes from the opportunity to serve – not from status or financial reward.

Vic served the people as an educator at Einstein, at Weill Cornell Medical College, and elsewhere. He not only instructed and mentored students, but he also inspired them. Vic trained thousands of physicians and other health workers, many of whom have become leaders in government, academia, civil society, and elsewhere. And each of them have now trained many more.

Vic had a profound influence on the career of many students. One student, for example, almost left medicine, which she considered misogynist and racist. But after hearing Vic speak, she discovered opportunities to make her career in medicine meaningful and consistent with her beliefs. She went on to become a local health officer and national public health leader, and she made significant contributions in reducing teen pregnancy, decreasing health disparities, and supporting health care reform.

Vic served the people as a scholar. For six decades, he wrote scholarly papers and gave numerous lectures with insight and vision, clarity and passion. In the early 1960s, he co-authored with Jack Geiger and Bernard Lown landmark papers in the New England Journal of Medicine and elsewhere on the health impacts of thermonuclear war. And he wrote many other papers about preventing war, reducing poverty, addressing racism, improving access to health care, and other issues related to health, peace, and social justice.

As a scholar, he recognized that research had to be conducted ethically. For years, he chaired the Institutional Review Board at Montefiore to ensure that research subjects were protected and respected.

Vic served the people as an organizational leader. He not only did things right, but he chose to do the right things. Where he saw suffering, he worked to heal it. Where he saw the threat of violence, he worked to prevent it. Where he saw social injustice, he worked to stop it. When the Allende government in Chile was overthrown in 1973 and many health workers there were fired, imprisoned, or killed, Vic led the response by Montefiore and APHA to publicize their plight, and to save and resettle Chilean health workers.

Now, let us recall some specific memories of Vic. Close your eyes and picture of one of your memories of him. Maybe Vic leading a demonstration against nuclear weapons or protesting Apartheid. Maybe Vic proposing a policy or a new initiative. Maybe Vic holding his beating metronome as he pointed out that every other beat represented a child's death that could have been prevented. Or, maybe Vic dropping hundreds of steel balls into a container, the pinging sound of each one representing an atomic bomb and the loud clanging noise of all of them together representing the global stockpile of nuclear weapons. Get a clear picture of your memory of Vic. And then think about the difference that Vic made in your life and the lives of so many others. Now open your eyes. These memories will always be with us, and so will Vic's influence on what we do and who we are.

I have more than 25 years of memories of working closely with Vic. We spoke almost weekly by phone and met several times a year. I remember his wisdom as we developed and co-edited books and wrote articles on war, terrorism, and social injustice. I remember his creativity as we presented lectures together. I remember his inclusiveness as we organized Peace Caucus sessions and Health Activist Dinners at APHA meetings. And I remember his vision as we established the annual APHA Award for Peace.

From Vic, I learned how to use science to support advocacy. From Vic, I learned how to communicate passionately. From Vic, I learned how to fully acknowledge everyone who contributed to a project. And I learned from Vic - and from Ruth - the essential components of the work we do: commitment, moral courage, and solidarity - solidarity as reflected in the words of the Chilean anthem that they loved: "The people united will never be defeated. The people united will never be defeated."

Nancy and I enjoyed our longstanding friendship with Vic and Ruth - getting together during APHA meetings, during their visits to Boston, and over lox-and-bagel brunches at their dining room table. We enjoyed conversations with them about politics and the arts. And we witnessed their mutual support, their deep love and affection for one another, and their pride in their families.

Now, both Vic and Ruth are gone.

Now, it is up to each of us and many others whom they inspired to carry on the work for health, for peace, and for social justice – to carry on the work with commitment, with moral courage, and with solidarity.

We miss their presence.

We mourn their passing.

And we carry them with us in what we do and who we are.

Barry Levy

February 4, 2018

Read the New York Times’ obituary: Dr. Victor Sidel, Public Health Champion, Is Dead at 86.