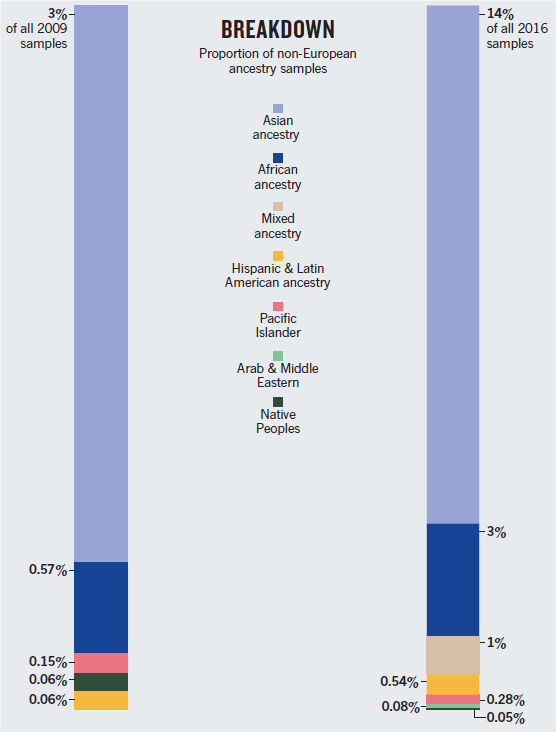

People of African, Latino or indigenous ancestry are underrepresented in many major genome studies, according to a new analysis by researchers from the University of Washington School of Public Health.

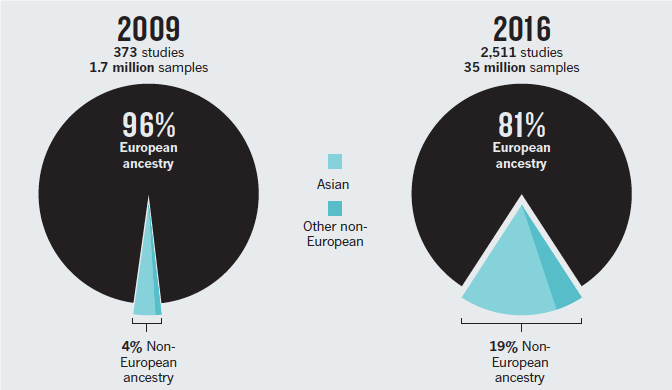

The analysis, published in a recent edition of Nature, notes that these minority groups make up less than 4 percent of the 35 million samples from 2,511 studies in the Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Catalog. Researchers suggest that the lack of inclusion in genomics research could have repercussions in clinical medicine.

"Studying the genomes of diverse populations is critical to achieve just distribution of the benefits of genomic medicine,” says Alice Popejoy, who conducted the analysis as part of her doctoral dissertation in the Institute for Public Health Genetics at the UW School of Public Health. “It’s not only the right thing to do, but it’s also crucial to the advancement of our understanding of disease biology and accurate estimation of disease risk in different ancestral populations."

Genome-wide association studies, which look for links between genetic variants and biological traits, are starting to reveal what underlies many disorders. However, the researchers caution, without a broader representation of human populations, insights into common traits and diseases could be missed or misinterpreted.

What’s more, because the interpretation of genetic test results for personalized medicine depends on previous population studies, insufficient diversity among research participants could affect clinical care. Emerging data, the researchers note, suggest that patients of African and Asian ancestry are more likely to receive ambiguous results from DNA testing or be told that they have genetic variants of unknown or uncertain significance.

Popejoy believes that the bias toward European populations is not always the result of researchers’ conscious decisions. Instead, she says, it comes from historical, systemic, racial and cultural inequities.

To correct the bias, Popejoy suggests investing more in community participation models of genomics research. She also proposes a concerted effort to improve the diversity of genome scientists by empowering those from underserved backgrounds to join the biomedical workforce and become leaders of research programs.

“I wanted to elucidate the issue of underrepresentation of underserved populations in genomics by using hard numbers,” Popejoy says of her published analysis. “The data speak for themselves.”

Popejoy collaborated with Stephanie Fullerton on the article. Fullerton is an adjunct associate professor of epidemiology at the UW School of Public Health and professor of bioethics and humanities at the School of Medicine.