Leading gun violence researchers presented cutting-edge methods for illuminating firearm violence in the U.S. at the Society for Epidemiologic Research’s 50th annual meeting last week in downtown Seattle.

The panelists explored new research that maps the shifting patterns of gun deaths and injuries across the U.S., uses space-time analysis to identify neighborhood features associated with gun assaults, and models the impact of denying guns to people with a history of alcohol abuse.

"Epidemiologists have done remarkable work” on gun violence in recent years, said Ali Rowhani-Rahbar, asssistant professor of epidemiology and adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, “despite really, really scarce resources.”

Rowhani-Rahbar, whose recent work in Seattle showed that gun violence spreads much like an infectious disease, organized the panel to advance the conversation around "this incredibly important public health, public policy and public safety threat in our country.”

Firearms are now the fifth leading cause of potential years of life lost in the U.S., said Bindu Kalesan, assistant professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. Both deaths and injuries from guns have increased in recent years, with more than 36,000 Americans killed by firearms in 2015, and another 85,000 sustaining non-fatal gun injuries, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But national and even state-level statistics conceal wide variations in firearm violence across the U.S., Kalesan said.

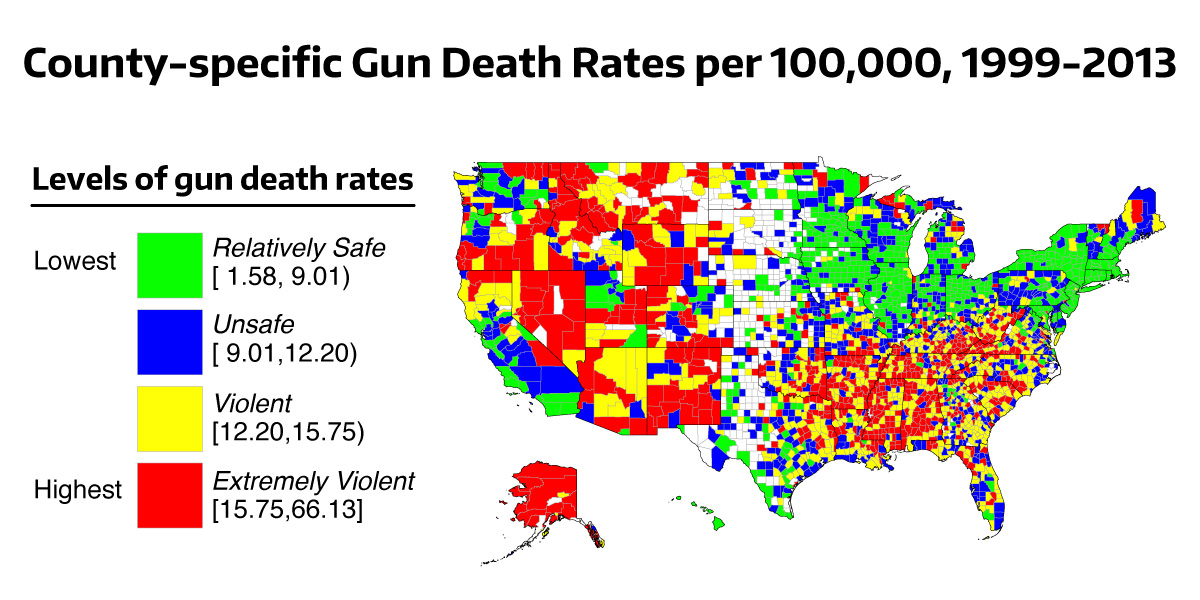

Kalesan’s recent analysis of county-level gun deaths between 1999 and 2013 found clusters of counties with very high death rates (see map above). The most violent counties, with gun death rates of more than 15.75 per 100,000, tended to be more rural and have higher rates of poverty and unemployment. A forthcoming paper by Kalesan and Rowhani examines changes in death rates in recent years, and finds that 11 states experienced significant increases between 2014 and 2015, including Maryland, Wisconsin and Rhode Island.

Gun deaths in the U.S. are “multidimensional, and there is wide variation within states,” Kalesan said. “State-specific programs and policies may not be adequate, but we might require community-specific interventions to address and prevent gun deaths and injuries," she said.

Even finer-grained mapping — down to a community’s street-level features — can also reveal patterns that set the stage for increased risk of gun violence, new research by Douglas Wiebe, associate professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perleman School of Medicine, has found.

In a novel space-time analysis, Wiebe reconstructed the moment-by-moment paths of more than 600 youth ages 10 to 24 as they moved about their Philadelphia neighborhoods, comparing the movements of those who were assaulted with a gun or other weapon with members of a control group who were not assaulted. The researchers also asked study participants who they were with at each point, how safe they felt, whether drugs or weapons were present, and other details of their day. In that way, the researchers were able to capture where the victims were “when things in things in their micro-environment changed,” Wiebe said.

Wiebe’s team then overlaid the youths’ paths onto 27 maps with features of the built and social environment, including risk factors such as alcohol outlets and vacant lots, and potential protective factors such as police stations and neighborhood cohesion. That allowed them to track the youths’ exposure to these factors as they moved around their neighborhood.

Being alone and in areas with more vacancy and vandalism increased the risk of being shot, the researchers found, while gunshot risk fell in areas with higher neighbor connectedness. “We do see people climbing this mountain of exposure on the time to getting assaulted,” Wiebe said.

One of the symposium’s three discussants, Sandro Galea, professor and dean at Boston University School of Public Health, praised Wiebe’s “elegant analysis” isolating features of the micro-neighborhood that contribute to the gun assault risk. But the full picture is more complex, Galea added. Gun violence results from the interaction of many factors, he said. Epidemiology has a “tough job” in trying to figure out where “the greatest impact is going to be when we look at things together and look at the emergent picture of cumulative risk," he said.

One known risk factor for both gun homicide and suicide is alcohol use, with about 34 percent of homicide perpetrators acutely intoxicated at the time of the event. Given that link, Magdalena Cerdá, associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, Davis, tested whether preventing gun purchases by people with a history of alcohol abuse would reduce gun-related deaths.

Using nearly a dozen data sources, Cerdá’s team constructed models to simulate “agents” representing 3 percent of New York City’s population. The researchers tested the effect on gun homicide and suicide of three firearm denial criteria: a driving-while-intoxicated (DUI) conviction in the past year, a DUI arrest, and alcohol abuse.

Projected homicide rates did not change under any of these denial criteria. Suicide rates fell only if the broadest criteria — any alcohol abuse — was applied. Even if such a broad prohibition could prevent some people from harming themselves, it would very difficult to implement, Cerdá said, and “concerns arise around legal and constitutional issues.”

While denying gun sales on the basis of alcohol abuse is not politically feasible, other measures can counter the widespread problem of alcohol abuse and related gun violence, Frederick Rivara, University of Washington professor of pediatrics and adjunct professor of epidemiology, said in response to Cerdá’s presentation.

In addition to expanding cost-effective alcohol screening programs and raising alcohol taxes, “we can try to address violence when we see it,” Rivara said. He and Rowhani-Rahbar, for example, are collaborating on a randomized trial of interventions with gunshot victims to break the cycle of violence.

More research on gun violence — and more funding — is still needed, the panelists agreed.

While gun violence research has seen an uptick in recent years, it still lags behind what Rowhani called the “golden years of gun violence research” in the 1990s, in large part due to restrictions on federal funding for firearms-related research.

Firearm violence research “lags far behind many other epidemiologic pursuits,” said panel discussant Charles Branas, professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “And if we could get even a fraction of the investment — intellectual investment and resource investment — to be able to look at this more closely, I think we could have a real impact on it as a nation.”

Galea urged fellow researchers not to forget the “core fundamental problem, which is the availability of guns.” There’s still much work that must be done to “show us how the danger is modified and what puts all at risk,” he said, “but doing the work ... does not exonerate us from dealing with the foundational problem.”

(By Allegra Abramo for the UW School of Public Health)