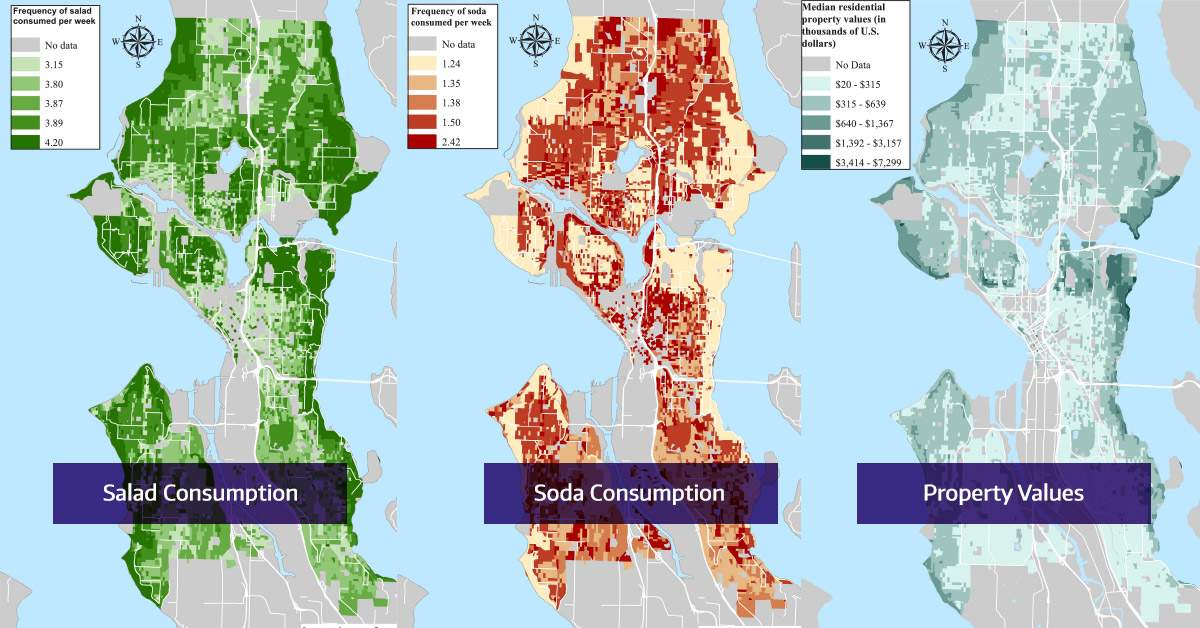

Seattle residents who live in waterfront neighborhoods tend to have healthier diets compared to those who live along Interstate-5 and Aurora Avenue, according to new research on social disparities from the University of Washington School of Public Health. The study used local data to model food consumption patterns by city block. Weekly servings of salad and soda served as proxies for diet quality.

The dramatic geographic disparities between salad eaters and soda drinkers were driven by house prices, according to the study. The lowest property values were associated with less salad and more soda; the opposite was true of the highest property values, after adjusting for demographics.

This is the first study to model eating patterns and diet quality at the census-block level, the smallest geographic unit used by the U.S. Census Bureau. The paper, published Jan. 9 in the journal Social Science and Medicine – Population Health, provides a new area-based tool to identify communities most in need of interventions to increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

Adam Drewnowski

“Our dietary choices and health are determined to a very large extent by where we live,” said the study’s lead author, Adam Drewnowski, professor of epidemiology and director of the Nutritional Sciences Program and Center for Public Health Nutrition at the School. “In turn, where we live can be determined by education, incomes and access to both material and social resources. We need a closer look at the socioeconomic determinants of health.”

Researchers geo-localized dietary data of nearly 1,100 adult participants of the Seattle Obesity Study based on their home addresses, and linked them to residential property values obtained from the King County tax assessor. Information on age, gender and race/ethnicity as well as education and annual household income were gathered via telephone surveys. Participants were also asked how often they ate salad and/or drank soda. Healthy Eating Index scores, a measure of diet quality, were calculated for each participant. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better diet quality.

People who ate more salad tended to have higher Healthy Eating Index scores associated with more healthy eating behaviors. People who drank more soda tended to have lower scores.

While the disparities of soda consumption by neighborhood were clear, there was no significant difference by age, income or education. However, researchers did find that Black and Hispanic residents reported more frequent soda consumption than White residents. Women tended to eat more salad than men, as did adults age 55 and older. Adults with some college education or more consumed salad more often every week than those with only a high school education or less. Also, people earning $50,000 or more ate more salad per week than those earning less than $50,000 annually. There was no significant difference in salad consumption by race or ethnicity.

“Salad and soda are the two hallmarks of a healthy versus an unhealthy diet,” Drewnowski said. “We now show that they tend to be consumed by different people with different education and incomes, living in different neighborhoods in Seattle.”

Researchers selected salad and soda because they were used as the proxy of diet quality in the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Study. They are also frequent targets for obesity prevention policy intervention. A good example of this is Seattle’s so-called soda tax, which took effect in January 2018.

“Interventions towards promoting healthier diets tend to focus on taxing soda, which is perceived as too cheap, and reducing the price of fresh produce, which is perceived as too expensive,” Drewnowski said. “Initiatives to replace soda with salad come across the issue of socioeconomic status and income purchasing power, and those are very complex issues.”

As more states and municipalities seek to develop targeted interventions for better health, they will need place-based tools to identify high-risk or high-need communities, according to the study.

The Seattle Obesity Study was a population based study of 2,001 male and female residents of King County, Washington. The aim was to examine the role of access to foods in influencing dietary choices and, thereby, contributing to disparities in obesity. The study recently expanded to include Pierce and Yakima counties. Drewnowski and his team plan to conduct similar research in those regions.

“We look forward to seeing those results,” Drewnowski said. “Yakima has a large population of Hispanics and the closest supermarket is 20 miles away; not to mention obesity looks very different in Yakima than it does in Seattle.”

Study co-authors are James Buszkiewicz, a graduate student in the Department of Epidemiology, and Anju Aggarwal, acting assistant professor of epidemiology, both from the School of Public Health. Drewnowski and Aggarwal are key investigators on the Seattle Obesity Study.