The Hanford Nuclear Site, built in Southeastern Washington in 1943 to manufacture plutonium for atomic bombs, remains one of the most contaminated worksites in the world. In a new report, students from the University of Washington School of Public Health found that workers injured and exposed to contaminants at the site face many barriers to receiving compensation despite the benefits of a recent state law.

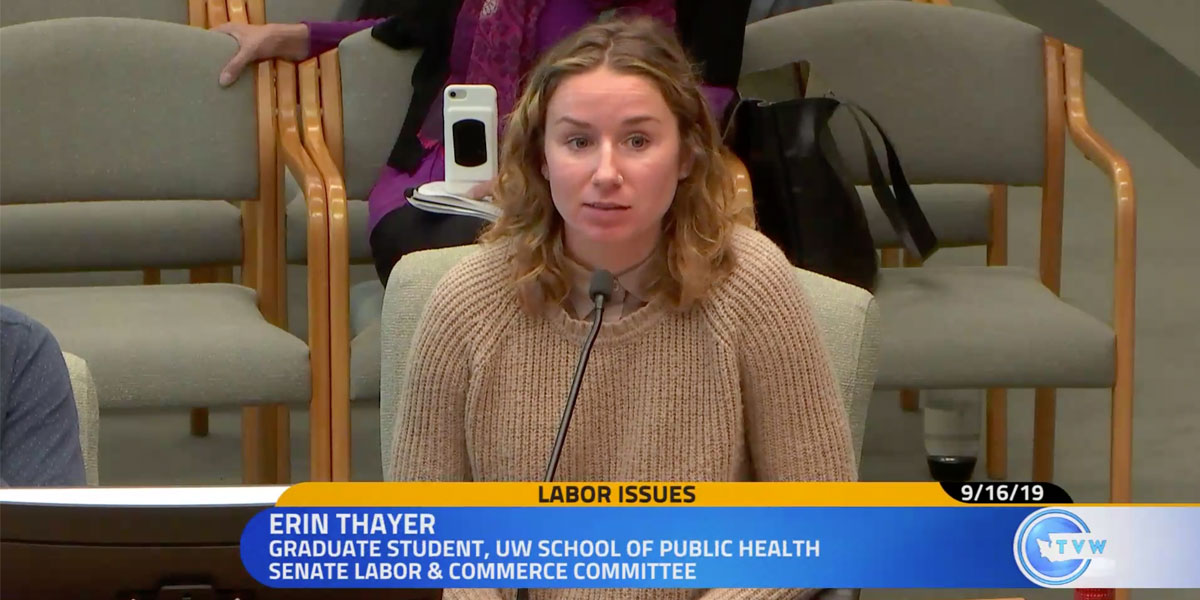

They presented their results Sept. 16 in Olympia to the Washington Senate Labor and Commerce Committee at the invitation of Senate Chair Karen Keiser (D-Des Moines).

Hanford workers, the report notes, commonly suffer from respiratory diseases, cancers and neurodegenerative disorders. The Hanford Presumption Law of 2018 – so named because it presumes these illnesses in Hanford workers were caused by exposure to workplace toxins – entitles them to workers’ compensation. However, Erin Thayer and Nick Locke of the Department of Health Services and Michael Cork of Global Health found that the Department of Energy (DOE) is denying workers and their families what the law promises.

![Entry sign at Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington [(CC BY-SA 3.0) TobinFricke]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Hanford_sign.jpg)

Despite the new law, Penser North America, the DOE's third party administrator, denies Hanford workers’ claims at five times the rate of other self-insured employers and has failed to meet the mandatory 60-day deadline in 98 percent of claims, Thayer and Locke, both MPH students, reported in Olympia.

“Meeting the workers suffering from diseases caused by toxic exposures brought our quantitative data to life,” says Locke, recalling a man whose 10-year-old claim was finally approved under the 2018 law but who has not yet received significant compensation. Because many of the workers suffered neurodegenerative disorders, Locke told the committee, they depend on spouses and the assistance of an understaffed local center to file and fight for claims. The center, their research revealed, is funded by the DOE. Locke says he hopes “our presentation reminded senators that there are many workers in this state who need their ongoing support.”

The students reached out to a Penser North America representative before publishing their report but received no response. As a for-profit company not directly regulated by the state, Penser was not represented at the committee meeting, but spokespeople for the Washington Department of Labor and Industries, which oversees compliance with the Hanford Presumption Law, presented to the committee that they have stepped in to allow claims when Penser has failed to rule by the deadline.

The students began their research, including public records evaluations and extensive interviews of workers, their spouses and union representatives, in a public health skills class (HSERV 572) taught by Professor Amy Hagopian, director of the Community Oriented Public Health Practice program. They completed the work as summer practicums in partnership with the Hanford Challenge, a nonprofit that promotes Hanford cleanup and worker safety. They were supervised by Executive Director Tom Carpenter.

Thayer says the presumption law and the positive legislative response to their report represent “important steps to simplify the process for workers and their families to get the compensation they deserve for their service.”