In Nigeria, anti-gay laws can lead to punishments including 14 years in prison or even death by stoning. Gay men and women are banned from holding meetings or organizing in groups, and anyone who supports the union of a gay couple could spend a decade behind bars.

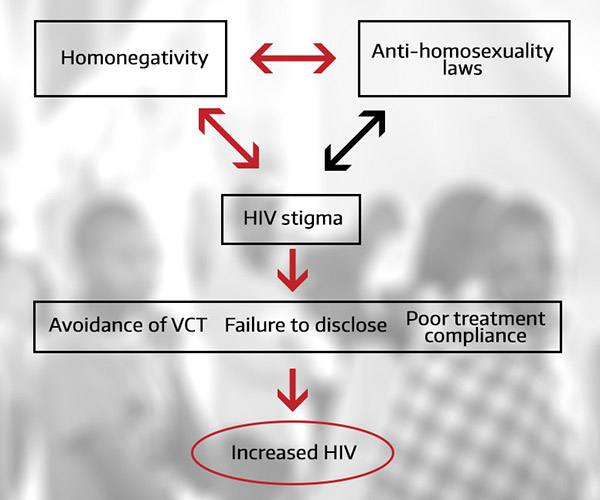

A new study from the University of Washington School of Public Health suggests laws criminalizing homosexuality, like those in Nigeria, reinforce stigma in ways that harm efforts to stop the HIV epidemic. In African countries, anti-gay laws precipitate fear and discrimination, and they block access to vital HIV prevention, care and treatment.

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, recognizes the negative role of stigma in the fight against HIV. However, researchers say the program has done little to address anti-gay legislation as the primary driver of stigma in Africa.

“The U.S. government is financially supporting efforts in PEPFAR partner countries, in most cases with lots of money,” says Aaron Katz, co-author of the study and principal lecturer of health services at the School. “Its interest is in helping those countries effectively contain the HIV epidemic, and so it has an obligation to help those countries use the best practices to do so.”

One approach highlighted in the study is through PEPFAR Partnership Framework agreements, country-to-country agreements meant “to foster a policy environment that would help reduce the pace of the [HIV] epidemic.” While most (14 out of 16) policy agreements between PEPFAR-funded African governments and the U.S. State Department call for stigma reduction, none even mention anti-gay legislation. SPH researchers say this is a missed opportunity.

Katz, also an adjunct principal lecturer in global health and in law, notes, while he thinks it is appropriate for the U.S. to step in, there needs to be a balance. “The partnership should respect the autonomy of the partner country and its right to make decisions it believes are in the best interest of its citizens,” he says. “I would say the U.S. has an obligation to support national decision-making, but not try to supplant it.”

According to Katz, a whole variety of national policies can influence the effectiveness of a country’s response to HIV/AIDS. For example, they can influence the availability of anti-retroviral medications; the affordability of care, especially to lower-income individuals; what health professionals are legally able to prescribe medications; protection of patient information; and the age at which young people can consent themselves to testing, counseling and treatment.

PEPFAR negotiated policy agreements with partner national governments between 2009 and 2012. The agreements were voluntary and they outlined PEPFAR’s financial and technical plans to support HIV prevention, care and treatment programs, as well as partner country plans for programming, policy reform and financing. PEPFAR has since abandoned this approach, according to Amy Hagopian, lead author of the study and associate professor of health services and global health at the School. Though it is not clear why.

In the study, published online June 5 in Global Health Action, researchers used a 2014 analysis produced by the U.S. Law Library of Congress to assess anti-homosexuality laws in 21 African countries receiving PEPFAR funding. They then examined PEPFAR policy agreements associated with those countries for evidence of attempts to reduce stigma by decriminalizing homosexuality.

Sixteen of Africa’s 21 PEPFAR-funded countries had laws characterized as harsh against homosexuality. Seven of these countries are among PEPFAR’s eight most-funded in Africa, including Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda. These countries are all former British colonies, which — compared to countries with other colonial legacies — have been found to have the harshest laws criminalizing homosexual conduct.

“Most of Africa’s anti-homosexuality laws were first motivated by Christian colonialists and the doubling down on the harshness of these laws has been fueled by modern-day missionaries of various ilk,” Hagopian says.

She explains that PEPFAR once promoted legislation in Africa attempting to criminalize the transmission of HIV, but “under subsequent administrations, the U.S. acknowledged evidence that criminalization promoted stigma and probably made HIV epidemics worse.”

Since the creation of PEPFAR in 2003 under George W. Bush, the U.S. has been a global leader in responding to the urgent need for the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS. Barack Obama renewed the program and tripled the investment in 2008. To date, the U.S. has dedicated about $60 billion to HIV/AIDS efforts around the world, but the future of the program is in doubt due to an 18 percent budget cut proposed by the new administration. This looming reduction would put millions of lives at risk and raise the possibility that the pandemic will reignite, according to an article from the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

SPH researchers say that decriminalization of homosexuality is a “midterm goal in the public health agenda.” Focus will need to turn to eliminating discrimination for gay people in employment, housing and other social determinants of health.

Researchers also say there is evidence of LGBT human rights movements across Africa pre-dating conservative U.S. influence. “In this sense, it’s similar to other historical struggles for equality, such as in apartheid South Africa, where we found the U.S. on the wrong side at first,” Hagopian says. “In retrospect, it’s not hard to know which side of social movements were right. The trick is developing an instinct to know in advance.”

Study co-authors also include Katz, Deepa Rao, associate professor of global health and of phsychiatry and behavioral sciences; Sallie Sanford, associate professor of law and adjunct associate professor of health services; and Scott Barnhart, professor of global health and of general internal medicine.

(By Ashlie Chandler)