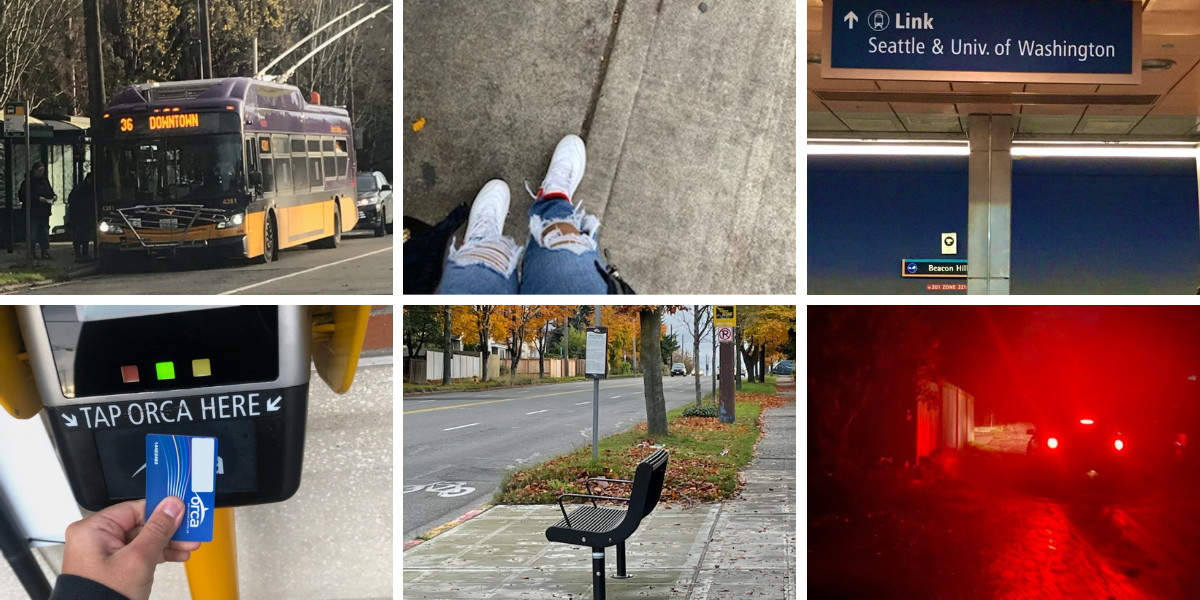

Images captured by youth for the study, which show their experiences transiting around the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Seattle.

Public transit is one of the few ways youth have to independently navigate to school or work, but they don’t always feel safe doing so. Youth of color in particular experience physical or verbal harassment on trains or feel unwelcome if they speak a language other than English in a public space. They pick their routes to avoid poorly-lit roads and are told by family members to be on guard and cautious in public.

Policies created around transportation and infrastructure don’t always include young people’s perspectives, but new research has been trying to change that. A study published Aug. 4 in the journal Family and Community Health shares the voices of youth of color from south Seattle on navigating transportation, as well as their recommendations on how to make mobility safe and accessible, such as free public transit for all. Researchers connected these youth with city and transit leaders, to share their recommendations.

“This whole study is about how our different identities affect our feelings of safety in public spaces,” said Evalynn Romano, who led the research as part of her Master of Public Health thesis at the University of Washington School of Public Health. “I think it’s underestimated how important access to transportation is for a young person’s wellbeing. That’s one of many reasons why youth should be involved in mobility justice conversations.”

The youth’s recommendation to make public transportation free for all has already seen great momentum. This summer, the Metro King County Council approved free public transportation for all youth 18 and under starting September 1. It’s one of many public transportation agencies in Washington state that have announced similar measures after the state legislature approved $1.45 billion in new transit support grants for agencies who provide free youth transit.

“So many factors were involved in that decision, but it’s so neat to have been advocating for this for a couple years now, and for something like that to happen is really special,” Romano said. “That's what I love about community-based research, is you can use it as a tool for advocacy.”

The research shows how mobility is a social determinant of health. The ability of a person to move safely through their neighborhood influences whether they can get an education or employment, whether they can exercise or access grocery stores. Factors like sidewalks, accessible public transportation, street lighting, and perceptions of safety all influence a person’s mobility.

Access to mobility is often inequitably distributed, with residents in wealthier, predominantly white neighborhoods having access to better city infrastructure and transportation than those in poorer neighborhoods, which are often the home to communities of color.

Inequities also exist when it comes to accessing safe mobility options. Bike helmet laws, transit fare enforcement, and police traffic stops disproportionately affect people of color. Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to die while walking and cycling than white Americans, according to research from Boston University School of Public Health and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. In Seattle in 2014, 23-year-old Oscar Perez-Giron was killed by a King County Sheriff after being removed from the light rail for not paying fare.

Geyciel C., a 16-year-old and one of the youth participants of the study, said her identity and those of her peers all impacted the way they felt on transportation or walking through neighborhoods.

“There’s a lot more caution, especially as a girl and as a POC,” Geyciel C. said, who takes the bus and light rail every day to get to school and walks to her internship. “Girls are always told that we have to be safe, we have to be cautious, and we have to be sure we’re aware of our surroundings.”

KL Shannon, one of the researchers on the study and a community organizer in Seattle, has many stories of how youth of color are often assessed as a threat in public spaces.

Her nephew, who is Black, started experiencing harassment on trains at age 14. Her 25-year-old friend who is also Black was on a walk in the wealthy neighborhood of Madrona and someone called the police on her. Shannon, who is Black herself, was accused of casing when she was young and learning how to drive: she had stopped for a break in the Madison Valley neighborhood to look at the beautiful homes, but as she began driving away, the police pulled her over and made her sit for an hour as they checked her ID.

“Disproportionately, people of color are vulnerable,” Shannon said. “We are the ones that are under attack. We are the ones that are not sitting at the table discussing how transportation impacts our communities, or the policies that are being implemented. That’s why mobility justice is so important, and why we have to push to be at the table and make sure our voices are being heard.”

The youth also shared concern for the safety of others riding public transportation. While the youth said that they felt vulnerable riding buses or light rail alongside people experiencing mental health issues, they also recognized that policing brought increased dangers to those experiencing these mental health challenges and toward communities of color riding public transit.

Ten youth of color participated in the study, which ran from Nov. 2020 to May 2021. All of the youth lived in the Beacon Hill neighborhood, one of the most diverse, though quickly gentrifying areas of Seattle.

The study used photovoice (a research method that involves photography to document experiences) as a technique for youth to share their experiences of mobility. The youth took pictures guided by mobility-justice-informed missions, such as “What are your general experiences getting around the Beacon Hill neighborhood?” or “What makes you feel unsafe?” They then convened in six virtual sessions and discussed their photos and responded to their peers’ experiences.

Researchers worked with the youth to co-organize a dissemination and advocacy plan, which led to the development of a forum in May 2021, where the youth shared their mobility experiences with the community, local public transportation leaders, city government officials, and media.

They also co-wrote an op-ed in the South Seattle Emerald, advocating for free public transportation as a way to make communities safer by reducing carbon emissions from cars, increasing safety from car crashes, and reducing pedestrian deaths that disproportionately impact people of color.

“Racism is a public health issue,” Shannon said. “It needs to be treated that way and needs to be addressed.”

Romano and Shannon said the study also speaks to the importance of including youth voices in research and policymaking from the very beginning, and paying them for their time and wisdom. The youth were all paid $15 an hour for their participation in this study and dissemination efforts, and the researchers still keep in touch with them to share paid opportunities around mobility justice in the community.

“We are the future; we should have a say on what goes on and we need to be able to talk about what youth are feeling,” Geyciel C. said. “We can help and we have ideas on how to better our community because we are a part of it. I would like transportation to be more reliable and safer for us.”

This study was one part of a larger study called The Participatory Active Transportation for Health in South Seattle (PATHSS) Study, funded by the UW Population Health Initiative. The study authors include Evalynn Fae T. Romano, graduate of the UW School of Public Health, who now works at Seattle Children’s and leads the The Custodian Project; Barbara Baquero, co-author of the study, co-principal investigator at PATHSS, and associate professor of Health Systems and Population Health in the UW School of Public Health; Olivia Hicks, PATHSS research assistant and undergraduate at UW,; Victoria A. Gardner, assistant dean for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion at the UW School of Public Health; KL Shannon, community partner at PATHSS and community organizer at Seattle Neighborhood Greenways; Katherine D. Hoerster, co-principal investigator at PATHSS and associate professor at the UW School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.