Photo credit: University of Washington

Loneliness has been increasing amongst young people globally, and researchers have been trying to understand why. While past studies have often looked at how an individual’s behavior could lead to loneliness, a new study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health takes a different approach by asking what societal factors may be linked to this trend.

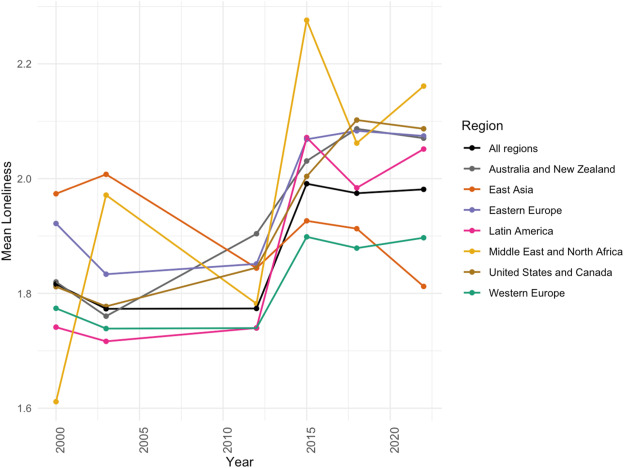

Led by researchers at the University of Washington School of Public Health, the study looked at how youth’s answers to loneliness questions in an international survey have changed from 2000 to 2022. With data points from over one million youth representing 38 countries, they found that loneliness has been increasing across many regions, with the largest increase between 2012 to 2015, and the second largest from 2015 to 2022.

Trends varied by region, with the Middle Eastern countries of Israel and Turkey reporting the highest combined score of youth loneliness in 2022, followed by the United States and Canada. East Asia, which includes data from Japan and South Korea, had the lowest score of loneliness, and was the only region to see a loneliness decrease from 2000 to 2022.

After seeing these increases across countries, researchers then asked whether country-level societal factors like COVID-19 mortality, public health distancing measures, internet use, unemployment rate, income inequality, and peacefulness had any link to youth loneliness.

While this study didn’t find that any of those six factors were associated with an increase in loneliness, these questions shape the beginning of an important new focus in the field of loneliness research in adolescents. Understanding possible social, global, and economic influences on youth loneliness can lead to policy changes or large-scale interventions to support mental health.

“We need public health interventions to address loneliness and mental health among adolescents, since the two are so connected.” said Sophie Freije, epidemiology doctoral candidate and lead author of the study. “I hope the study shows one template you can use to look at societal factors related to loneliness. There are just so many factors that can be looked at that are really exciting and understudied.”

Other societal factors Freije is interested in seeing studied are how social safety net policy changes connect to loneliness, because these can indicate whether a population’s basic needs are being met. Freije is also curious about how measures of prosocial values are connected to loneliness; for example, does loneliness increase or decrease when individualism or collectivism is emphasized in communities. She also wants to see more measures of income inequality studied to see how that influences loneliness.

Studying loneliness in adolescents is important because these feelings can lead to health risks, including poor sleep, increased stress, and mental health disorders.

“Social connection is uniquely important in adolescents,” Freije said, pointing to how teens start building bonds and identity outside of their family unit. “Loneliness can be particularly stressful if an adolescent experiences it compared to someone in another age group.”

While the team’s research didn’t find factors that could have led to increases in loneliness, they did find connections between societal factors and decreases in loneliness.

First, they saw a connection between a country's increase in unemployment and a decrease in youth loneliness. These findings surprised researchers, Freije said, because they expected to see the opposite trend. However, she adds that these findings may speak to some important nuances in the data and methodology of this study.

With unemployment, past research that focused on an individual’s experience found that unemployment often increases feelings of loneliness. This is often due to people’s basic needs not being met from economic hardship as well as social stigma associated with unemployment. But Freije’s study looked at this trend at a societal rather than individual level, and amongst countries that generally have social net programs that can support large groups of people economically during unemployment. A separate study that also took this societal lens found similar results of lower loneliness alongside higher country-level unemployment rates.

Second, researchers were able to weigh in on common questions around internet use: does it connect communities, or isolate them? The researchers chose to focus on internet access rather than smartphone and social media use because past research has already looked at this connection and found an increase in loneliness. But by studying internet access more broadly and at a societal level, their study found that an increase in internet use over time was associated with a decrease in loneliness.

Some argue that the internet allows people to connect with others, especially those they share common interests with, and even meet them offline. But another theory argues that the internet displaces those offline interactions, isolating people and leading to more loneliness. The researcher’s findings align with the idea that the internet can be an important tool for connection.

The survey data used in this study represents 1.2 million adolescents aged 15–16 across 38 countries that make up the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. These youth took the Programme for International Student Assessment in the years 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2022, which included six questions about loneliness in school: “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things),” “I make friends easily,” “I feel like I belong,” “I feel awkward and out of place,” “Other students seem to like me,” and “I feel lonely.”

This is one of the most recent studies to look at multinational estimates of loneliness, using data that goes up to 2022. Because the data covers a period in time after many COVID-19 lockdown measures were lifted, it also provides a look at how loneliness levels persisted beyond the pandemic. Many studies observed the acute impacts of loneliness due to lockdown measures, but Freije points out that loneliness was a public health concern amongst youth well before that.

“Regardless of the pandemic, loneliness has been an issue on the rise,” Freije said.

The study’s authors include Sophia L. Freije of the University of Washington School of Public Health (UW SPH) Dept. of Epidemiology; Isaac C. Rhew of the UW SPH Dept. of Epidemiology and the Dept. of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the UW School of Medicine; Yolanda N. Evans of the Dept. of Pediatrics in the UW School of Medicine and Division of Adolescent Medicine, Seattle Children's Research Institute, Seattle Children's Hospital; Kwun Chuen Gary Chan of the UW SPH Dept of Biostatistics and Dept. of Health Systems and Population Health; and Daniel A. Enquobahrie of the UW SPH Depts. of Epidemiology and Health Systems and Population Health.