In 2000, the United States declared measles to be eliminated, however declining vaccination rates and the resulting increase in measles outbreaks have led to growing concern that the US may lose elimination status. Washington state experienced two large measles outbreaks in 2019, with the majority of cases cropping up among unvaccinated individuals. With 87 individuals contracting the measles disease, these outbreaks led to the most cases the state had seen annually since 1990.

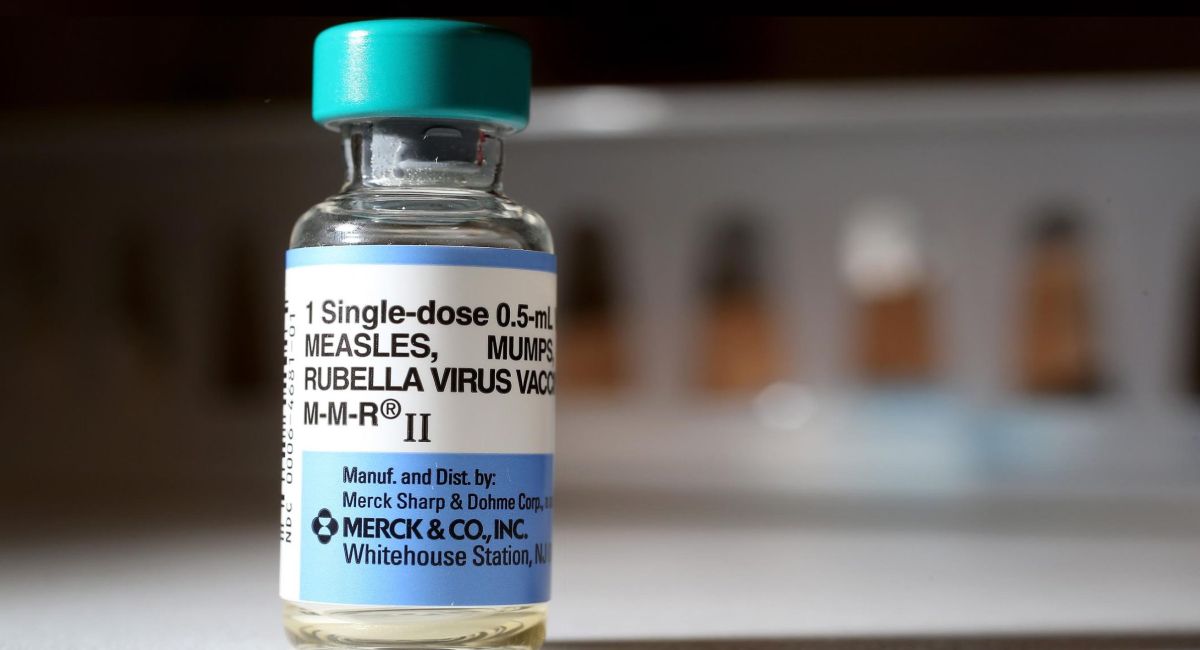

Measles can be particularly harmful for children, as it is a highly contagious virus, which can spread rapidly in schools or childcare environments if some of the children are not vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). Additionally, some children or community members may be immunocompromised and/or unable to get vaccinated, making them particularly vulnerable during preventable measles outbreaks. In response to the 2019 outbreak, Washington state passed EHB 1638, which specifically targeted the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) school vaccine requirement by removing the allowance for personal belief exemptions (PBEs). EHB 1638 applied only to the MMR vaccine and allows for PBEs for other school required vaccines, such as the polio vaccine. PBEs are a provision in state law which allows parents to exempt their children from the school vaccine requirement if it contradicts parental beliefs beyond those considered religious or spiritual beliefs. These exemptions can include moral, philosophical, or personal beliefs that relate to vaccines. Recent findings published in the American Journal of Public Health by researchers at the University of Washington and the Washington State Department of Health, evaluated the effects of this legislation on MMR vaccination and exemption rates to determine whether removing PBEs is an effective approach to increase overall vaccine coverage statewide and in under-immunized communities.

The study found that non-medical exemption rates for school-required vaccines, which had been increasing since 2014, saw a dip after EHB 1638 was passed. By comparing MMR immunization rates five years before and three years after the policy, researchers found a 5.4% relative increase in MMR vaccination rates among kindergartners and a 41% decrease in exemptions overall for MMR vaccines. While religious exemption rates saw a 367% increase during this period (from 0.3% to 1.4%), the study showed an overall net increase in the rates of MMR immunization following EHB 1638. Most notably, counties in Washington state that had been directly impacted by the measles outbreak and had MMR coverage rates below the statewide average prior to EHB 1638 saw a substantial increase in MMR coverage rates.

This policy provided ripe conditions for a study, since until 2019, parents could waive immunization requirements by claiming one of four exemption types: medical, PBEs, religious, or religious membership. EHB 1638 only removed one type of exemption and for just one school-required immunization. Researchers used Oregon as a control state for the study, as it had not passed any measures to limit exemptions despite also being impacted by the 2019 measles outbreak. This allowed researchers to show the effects of the policy while controlling for cultural and political similarities and proximity between Washington and Oregon.

Low immunization rates are what allow outbreaks like the one in 2019 to take hold. “Most of the prior research has been done in California, where personal belief exemptions (including religious exemptions) are no longer permitted for any currently-required school vaccination,” says Julia Bennett, a UW Epidemiology PhD research student. But Bennett says the targeted nature of EHB 1638 in response to a recent measles outbreak is what makes this study unique. EHB 1638 only applies to MMR vaccines and still permits religious exemptions. Compared to California’s approach to eliminate all non-medical exemptions, the Washington study not only showed data about the change in vaccination rates, but also hypothesized how and whether parents sought out alternative MMR exemptions.

“This is an important study to show the effect of legislation in increasing vaccine rates and prevention of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases,” says Dr. Helen Chu, associate professor in the UW School of Medicine. In fact, this is the first study to assess the effect of a statewide policy on PBE removal and the results suggest that eliminating PBEs while allowing for other exemption types may be an effective approach to increase MMR coverage in schools.

Although some parents did appear to pursue religious exemptions in response to the policy, there were also a number of people who opted to get immunized. These results have important policy and public health implications to protect communities from preventable diseases. Tyler Moore, an epidemiologist with the Washington State Department of Health, says future studies would provide a more granular look to see what is going on in a given school district. “A lot of what we’re looking at in this report is aggregated school-level data and assessing the trend in rates over time can only tell us so much about the bill’s impacts. It will also be important to continue to assess the long-term impact of this bill.”

This project was a collaboration with WA DOH and UW—including Julia Bennett, Mayuree Rao (MS 2022 graduate, Health Systems and Population Health), Helen Chu (UW Medicine, Global Health & Epi) and Brad Wagenaar (Global Health & Epi).

Original story on Epidemiology website