Each year, the School honors two outstanding graduate students – one doctoral and one master's – for their academic excellence and commitment to public health. This year's winners of the Gilbert S. Omenn Award for Academic Excellence are Miriam Calkins, who received a PhD in environmental and occupational hygiene, and Katrin Fabian, an MPH graduate in global health.

Miriam Calkins, PhD in Environmental and Occupational Hygiene

For road crews, roofers and other construction workers who spend long hours working outside, global warming is a trend with potentially life-or-death consequences.

How do you measure the health effects of heat exposure on individual workers? This question was at the heart of Miriam Calkins’ research as a doctoral student in the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences.

Calkins speaking at the SPH graduation celebration.

Calkins found that as temperatures rise, construction workers are at greater risk for falls, broken bones, concussions and other traumatic injuries. Her studies also showed increased risk for heat-related illnesses such as dehydration and heat exhaustion on hotter days for the working-age population.

Most surprising: Workers between 15 and 64 years old, an age group generally considered resilient, had the most on-the-job injuries and illnesses.

Heat-related illnesses are anything from minor heat rash to very severe heat stroke that may lead to death. When the body gets overwhelmed and can’t maintain its normal functioning, the core body temperature can rise, leading to damage to the kidneys and eventually the brain.

Calkins was one of the first to document the connection between heat exposure and injuries using data from the state worker’s compensation system, said Michael Yost, chair of the department. Her research has shown there are more workers at risk than previously known. It also suggests a need for additional protection for outdoor laborers, she says. Under Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) law, employers are responsible for providing safe workplaces. This includes protecting workers from extreme heat. Some employers are already doing this by offering training sessions on heat exposure and equipping workers with cooling neck towels and other protective gear.

“Even prior to someone’s awareness of being too hot, there is an increased risk of injuries,” Calkins said. “This means that even on a day not considered too hot for working, the industry still needs to be prepared.”

Calkins doing testing in the field.

As a master’s student in the department, Calkins used local Emergency Medical Service call data from 2007 to 2012 to understand the impact of extreme heat on worker injury. She analyzed meteorological data for the same time period using humidex, a temperature index that combines the effect of heat and humidity to gauge how hot the weather feels to a person.

Calkins found that a humidex at or above 85.5 degrees Fahrenheit increased risk for basic life support call response by 8 percent. When the humidex hit 98 degrees or more, calls for advanced life support rose 14 percent across all age groups compared to days with lower temperatures.

Calkins recently began a two-year fellowship with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, where she is measuring heat and particulate matter exposure among wildland firefighters.

“I have an appreciation for how difficult it is to actually measure what workers are exposed to in the environment,” she said. “We need more information to understand heat exposure, and I want to refine how exposure is measured and ultimately develop safer work conditions.”

(By Amanda Pain)

Katrin Fabian, MPH student in Global Health

People in Liberia experience what Americans call depression, but there’s no translation for the word in local languages. Instead, they use phrases such as “I’m thinking too much” or “my heart fell down.”

According to Katrin Fabian, a recent graduate from the Department of Global Health, words for depression aren’t the only things lost in translation – treatments are, too.

“Mental health is experienced and communicated in different ways in different settings,” says Fabian, who received her master’s in public health earlier this month. “Understanding mental health in local contexts is important in order to better identify people who need support.”

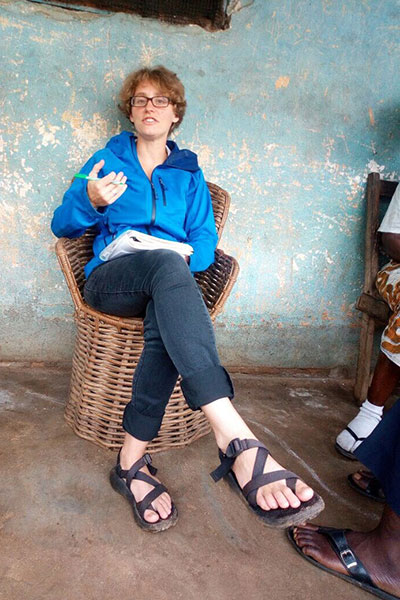

Fabian doing fieldwork in Liberia.

She recently led a six-month project in southeast Liberia, a country ravaged by civil war and a recent Ebola epidemic, to develop a tool to identify and treat people with mental suffering. She catalogued idioms in their local context and found culturally specific expressions of anxiety and depression.

The study could lead to more appropriate treatment models that make sense for the community and the tool, called the Liberian Distress Screener, could help practitioners reach a wider spectrum of potential patients.

“We need to take time to understand how other cultures experience mental distress, otherwise we are imposing our worldview and that’s problematic,” Fabian says. We see this often in international development, Fabian adds, which she studied as an undergraduate at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania.

“By taking a step back and figuring out the mental health needs of a community before coming in and providing help, we have a chance to create a paradigm of success that is informed by the communities themselves instead of by what we think is best,” she says.

This work is "the first structured implementation science project focused on improving public-sector delivery of mental health care in Liberia," according to Brad Wagenaar, who was Fabian's mentor on the project. Wagenaar is a UW acting assistant professor of global health and, at the time of the study, was director of research for Partners in Health (PIH) in Liberia. PIH is a Boston-based nonprofit health care organization founded by Paul Farmer.

Mental health is an emerging area and one of the UW Population Health Initiative’s grand challenges. Over the last decade, the global burden of disease has shifted from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes and mental illness. A 2016 study in The Lancet found that the global burden of mental illness accounts for 32 percent of years lived with disability. This is the prevalence of a disorder multiplied by the loss of health linked to that disability.

Fabian with her research partners.

Fabian first realized the importance of context while working with folks struggling with drug and alcohol addiction. She managed programs for at-risk youth and adults at wilderness rehabilitation centers in Utah and Colorado for two years prior to the UW. Compared to regular rehab centers, wilderness programs involve outdoor or adventure therapy on top of cognitive behavior therapy and detoxification programs.

“People come in with a laundry list of disorders, but it really takes getting to know people’s history and circumstances to be able to connect,” she says. She learned that reshaping certain factors could go a long way towards treatment for some, whether it was empowering youth to recognize their self-worth or connecting people to peer support. “It’s always going to be about more than just receiving a diagnosis and taking medication."

At the UW, Fabian has gained skills and knowledge to influence the systems that cause people to need these programs in the first place. She’s considering returning to Liberia to develop PIH’s research program and she plans to pursue a PhD in a few years.

“I hope to continue to learn and be involved in working to dismantle harmful systems and helping to build health equity,” she says. “I want to help redefine how we engage with communities and health systems by prioritizing local voices.”

(By Ashlie Chandler and Caroline Liou)