In the late 1970s, Chris Hurley and a ragtag group of idealists transformed an abandoned tavern in Seattle’s Pike Place Market into a community space for a different sort of patron.

They patched up holes in the old tiled floor and added a waiting room. They replaced dark, dingy booths with small exam rooms. They converted the bathroom into a lab and the store room into a pharmacy. By the end of the summer of 1978, the Motherload Tavern had a new name, Pike Market Medical Clinic, and it was delivering health care to thousands of downtown Seattle’s low-income residents.

“We were just a little collective of people working out of an old bar,” said Hurley, a community organizer who, at age 22, pursued a Master of Health Administration (MHA) at the University of Washington School of Public Health.

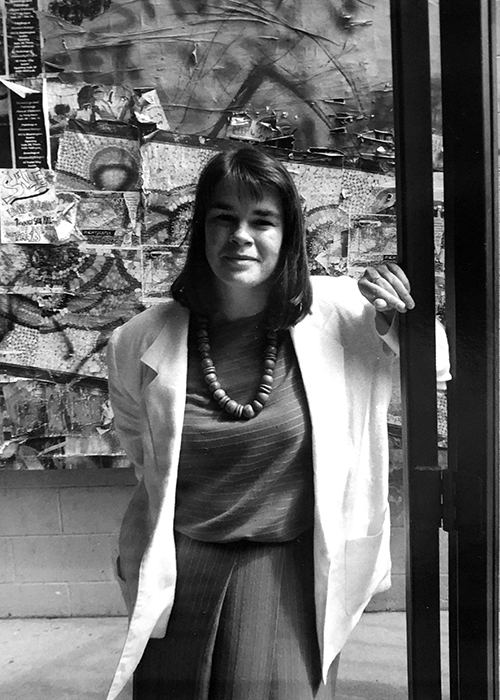

She graduated from the MHA program just a year before the clinic opened. She would later become a leading figure in Seattle’s community health center movement and go on to work with a number of organizations to reduce barriers to health care, safe and stable housing, and other social services for the elderly, the homeless and LGBTQ individuals. Hurley was recently named the School’s 2020 Distinguished Alumnus – the School’s highest honor, which recognizes distinguished service and achievement in public health. She will be honored at a Jan. 16 event, where she will share highlights from her career in a moderated discussion.

The Pike Market Medical Clinic was one of more than a dozen community clinics in Seattle at the time that provided health care for low- and middle-income individuals lost in a hinterland beyond costly traditional medical care. The Black Panthers opened Carolyn Downs Family Medical Center to serve the Black community, feminist groups started women’s health clinics and the University District’s Open Door Clinic and Capitol Hill's Country Doctor Clinic cared for a growing counterculture. In downtown Seattle, the new clinic served a large cluster of single, older adults hidden in the hotels and apartments above the city streets.

Most housing in the downtown area was single room occupancy, with residents who had aged out of working class jobs renting eight-foot by eight-foot rooms that fit a bed and sometimes a small table. This forgotten population included retired U.S. Merchant Marines and other seamen, people who had worked in retail or as cooks all their lives, and labor union members.

“One of the most persistent things we heard from this group was that they couldn’t get doctors to accept them as patients,” Hurley said, as a majority were insured through Medicare, which many doctors refused to take as payment for services. Additionally, this population bore the brunt of health impacts caused by the steady destruction of affordable housing in the downtown area in the 1970s and 1980s. They were suffering from chronic diseases, injuries and mental health issues. They were also experiencing loneliness and social isolation, risk factors that have since been linked to poor health and a higher risk of mortality.

Patients not only faced health issues common to people their age but also problems brought on by their socioeconomic status, including high blood pressure, hypertension, diabetes, poor nutrition and foot problems.

As executive director of the clinic, Hurley listened to the community about their challenges and needs and worked with clinic team members and patients to design services. The clinic developed a national reputation for its geriatric services, “offering specialized services rarely seen in other primary care settings,” she said, “including community nursing outreach, foot care, housing advocacy, social work and internal medicine providers.”

The clinic was recognized as an innovative model of care and service by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 1980. That same year, the clinic moved from the aging Pike Market building to more modern digs in the Livingston-Baker building off Post Alley. “There’s nothing like being in an alley for prestige,” Hurley joked.

A key lesson learned through this experience, according to Hurley, was the importance of coalition building and partnerships. This was particularly important when she organized and led a group of stakeholders to develop the Pike Place Market Foundation, a source of private funding for the clinic and other social services organizations in Pike Place Market. The foundation has since raised $30 million, ensuring the clinic's sustainability.

Another lesson, one she had carried over from graduate school, was that "you need to include communities in any planning and decision-making around their health care needs.” These are lessons she has continued to pass on to the next generation of health care and public health leaders as a core faculty member of the UW School of Public Health’s Community-Oriented Public Health Practice Program.

Community health centers like the Pike Market Medical Clinic grew out of the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s, as activists found ways to focus their energy on more tangible goals locally. In much the same way, Hurley’s interest in health care began because of her passion for feminism and social justice.

Originally from northern New Jersey, just outside of Manhattan, Hurley studied political theory in Ohio before moving to Bellingham, Washington. She was 20 years old, it was the early 1970s, and Bellingham – like Seattle and San Francisco – was a “hotbed of leftist thinking.”

“It was such a fabulously dynamic, disruptive time when there were lots of things to be involved in - or protest,” Hurley said, from the Vietnam War and nuclear power to Native American and women’s rights. “I was all mixed up in that time and place, and I was working on things that I believed in.”

Hurley got involved in a women’s health collective called the Elizabeth Blackwell Women’s Health Brigade. She started to travel to Seattle more often to visit with women’s clinics and met people involved in the rich community health movement. “I started to see the broader picture of community health beyond the pelvic exam,” she said. Friends put her on to the UW’s MHA program and a meeting with Allan Blackman, a professor in the program at the time, sealed the deal. Blackman would later become her adviser.

“I probably visited him in my white painters bib overall,” Hurley said. “I was very young when I went to graduate school, but I was persistently interested in new things and the MHA program was a good way to get smarter at figuring out how to be a meaningful participant in the world.”

Hurley was part of a small group of students in her cohort drawn to do community-based work. She had no desire to be a hospital administrator or health system executive but the program helped her to understand how the health system worked and “where the edges were that you could play with.”

Hurley has since pushed many boundaries. In the 1990s, during the AIDS epidemic, she was part of a community planning effort to change the way that care could be provided. The coalition took qualified nurses out of the hospital and placed them in a care setting for people with AIDS at the end of life. Seattle’s Bailey-Boushay House was the nation’s first nursing home of its kind. At the time of its founding, a death from AIDS occurred in Seattle nearly every day. Hurley led the home through “a dynamic and demanding environment of social, political and public health challenges and change,” she said. “I learned more about what it means to be a human being while at Bailey Boushay than any other place.”

At Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (now Kaiser Permanente Washington), she led the development of an innovative risk-based breast cancer screening program and, at Eastside Hospital, partnered with Public Health – Seattle & King County to provide maternity services to 150 low-income women annually.

Later in her career, she worked with the Committee to End Homelessness to design and secure funding for a social services program that diverted mentally ill homeless individuals from jails into safe, stable housing and treatment. She also worked with the county health department to expand a respite program into a 34-bed medical respite facility – now called the Harborview Respite Center – that would provide short-term housing and health care for homeless patients discharged after hospitalization. Hurley was integral in securing funding from eight area hospitals and building the facility in a low-income housing community.

Hurley's resume is a scroll. What's she most proud of? She said, "Sometimes it's 'the goose grocer.'" She is referring to The Goose Community Grocer on Whidbey Island, a one-of-a-kind partnership between Goosefoot, a nonprofit organization, and The Myers Group, a family-owned business that operates grocery stores, hardware stores and gas stations. When Hurley joined the nonprofit, it was in debt and she had to figure out how to make one of its last purchases, an old shopping center, viable. The shopping center now houses the Goose Grocer, which reinvests about a half a million dollars a year into the community to promote health, well-being and economic development.

"I'm most proud of that because it's so massively successful and I got to lay myself off," Hurley said. "It was a wing and a prayer, a desperation act. And it worked."