Unable to find work in the male-dominated field of chemical engineering in her home country of Thailand, Nuttada Panpradist changed course and, in the process, discovered a passion for global health and innovation.

Nuttada Panpradist in Thailand

“Job descriptions specifically listed ‘male under the age of 35’ as a requirement,” recalls Panpradist, who earned a bachelor’s degree in petrochemical engineering and graduated near the top of her class (fourth out of 154 students). “I love chemistry, but the field wasn’t welcoming to women, and it still isn’t today.”

Panpradist instead took a job selling medical diagnostics and alternative medicine. She saw how science and technology could have an impact on health care, which often seemed out of reach for some people. Disappointed by gender inequality and health disparity, she vowed to one day innovate affordable and accessible solutions to population health issues.

“I was learning a lot about anatomy, and I realized that our bodies were chemical engineering machines and I wanted to understand more about it,” Panpradist says. “I saw how I could make an impact on the health of people around me and the world, while enjoying the science I truly love.”

In 2009, Panpradist moved to Washington state to explore educational opportunities; it was, she says, “the closest state to get to from Thailand.” She got a certificate in pharmacy technology from Pima Medical Institute and another certificate in nanotechnology from North Seattle Community College. While there, she met Paul Yager, a professor of bioengineering and adjunct professor of global health at the UW.

Nuttada with her father at Pike Place Market

“I really wanted an internship at the UW,” Panpradist says. “I told him about my life and what it took to get here, and conveyed how much it would mean to me to receive his mentorship.”

Her pitch worked, and Panpradist earned a place in the Lutz Lab at the UW’S Department of Bioengineering. Under the supervision of Barry Lutz, now an associate professor, Panpradist began developing point-of-care devices for detecting HIV and tuberculosis (TB) infection. Today, as a PhD student in bioengineering and a certificate student in the School of Public Health, she is confronting one of the world’s largest public health issues – drug resistance.

“It’s an emerging issue in HIV surveillance,” Panpradist says. “We tend to scale up treatment without knowing whether a person is resistant to it.”

The HIV virus is a constantly moving target. It accumulates mutations and develops into strains that are resistant to a certain drug. When drug resistant strains go undetected, clinicians may prescribe a medication that is in limited supply to patients on whom it is ineffective. Those patients may unknowingly transmit the resistant virus to others.

“At some point, if we keep doing this, we won’t have the drug to administer to anyone anymore,” Panpradist says. An existing laboratory process – called oligonucleotide ligation assay, or OLA – allows clinicians to identify HIV drug resistance. However, the complexity of the process has prevented adoption in low-resource labs, such as those in developing countries.

Nuttada (third from left) with undergraduate researchers from the Lai and Lutz labs at the UW

Panpradist and a team of undergraduate researchers simplified the steps and designed an easy-to-use lab kit called OLASimple, which looks for mutations caused by the HIV virus. The lab kits will be rolled out in Kenya this June with help from Michael Chung, associate professor of global health and of allergy and infectious disease and adjunct associate professor of epidemiology at the UW.

While developing the lab kit, the research team saw potential to make the diagnostic test completely equipment free. They proposed OLASimple 2.0, a low-cost tool similar to a pregnancy test that alerts a single user to drug resistance and HIV viral loads, and can do so as early as five days after possible HIV infection.

“With this tool, clinicians can pick the right medication for each patient,” Panpradist says. “If you can make instant noodles, you can use this test.”

What does that mean exactly? Panpradist uses pad Thai, a popular dish from Thailand, as an example. When you make pad Thai, she explains, you soak rice noodles in hot water and make the tamarind sauce. “You need to add all the ingredients at the right proportion, otherwise your pad Thai is going to taste terrible,” she says. “If I pre-made pad Thai, then dried it and packaged it, all anyone would need to do to cook it is add water.”

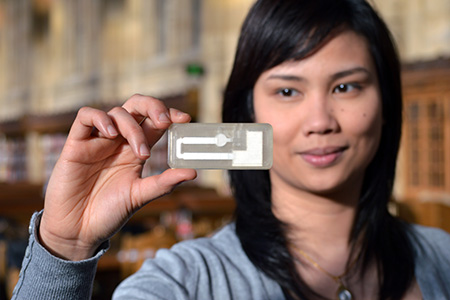

OLASimple's at-home diagnostic test works the same way. Panpradist and her team have proposed a pre-made test packaged in a credit card-sized plastic applicator. “You just add fluid and wait an hour for results,” Panpradist says. Traditional lab tests can easily take nine hours.

Nuttada with the rapid HIV test, OLASimple

The initial idea for OLASimple – a collaborative effort by Lisa Frenkel, James Lai and Lutz – was funded in 2012 through a seed grant from the Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents and Children, or Global WACh. The program, within the Department of Global Health, teamed up with the Coulter Foundation to offer support for collaborative research addressing the clinical needs of women and children.

Frenkel, a professor of pediatrics and laboratory medicine and adjunct professor of global health, and Lai, a professor of bioengineering at the time, connected while giving a joint lecture for the Global WACh Bioengineering Solutions course. The Frenkel Lab developed and validated the original OLA laboratory process and undergraduate researchers from the Lai and Lutz labs have worked with Panpradist to make the process more accessible.

OLASimple has since received various monetary awards, including a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Also, Panpradist recently won a coveted $50,000 grant from Massachusetts General Hospital to make the equipment-free OLASimple a reality.

She credits much of her success in global health innovation to the SPH program, to which she is now a certificate student. “Without Global WACh, I wouldn’t be here,” Panpradist says. One of the most valuable aspects, she notes, has been the ability to exchange ideas with other students, researchers and clinicians across disciplines. For example, she collaborated with MPH student Diana Marangu, a clinician in Kenya, to design a diagnostic test for TB. The project was funded by a Global WACh seed grant in 2014 and now has a two-year grant from the NIH.

Nuttada in Seahawks gear

“It takes more than good science to get technology into the hands of users – implementation is really important,” Panpradist says. “The certificate program is designed for students like me, who are enrolled in other degree programs, but want to see how they can contribute to global health solutions.”

Panpradist believes strongly that, by bringing people together – clinicians, communicators, chemists, social workers, people who like to build things – we can tackle population health problems from different angles. The UW School of Public Health, she says, is the perfect place for synergy.

“Collaboration is key to innovation,” Panpradist says. “No one can build anything alone.”

Panpradist’s engineering skills extend well beyond the lab. She enjoys building furniture, doing DIY home designs, cooking and food carving. If you have no idea what food carving is, check out her blog at www.npoutsidethelab.com. She also loves playing badminton and watching the Seattle Seahawks.

(By Ashlie Chandler)

Originally published: 2017

Currently, Nuttada is a PhD student in the Department of Bioengineering under the supervision of Dr. Barry Lutz. Her research focuses on developing point-of-care devices for detecting HIV/TB infection and drug resistance.