Beti Thompson set out to teach at a small liberal arts college, but ended up doing cancer prevention work with underserved communities. Her projects – from eastern Washington's Yakima Valley to New Mexico and Chile – have raised awareness about cancer while inspiring young scientists to go into public health work. Her innovative projects include a "colossal colon" and home-health parties.

The Colossal Colon

What is the "colossal colon?"

It's 10 feet high and 20 feet long and looks like a colon – with polyps and cancer and normal tissue. Last summer, we had it up in the Valley in a variety of venues. More than 2,500 people walked through it. We had a tremendous increase in knowledge.

Is it part of a larger project on cancer prevention?

It's part of the outreach we do at my Community Networks Program Center (CNPC), which works in a couple of counties in Eastern Washington. Its main goal is to get people more aware of cancer research and to encourage them to get screening. We also provide opportunities for free and reduced-cost screening. At the other end of the continuum, we're looking at cancer survivors and providing the resources people need to cope. Until we came out into the Valley, there were no survivorship classes in Spanish, only English.

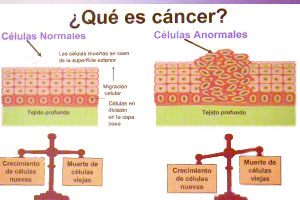

A chart from a home health party

Tell us about your home health parties.

They're like Tupperware parties, only we're selling health. And we don't charge people for it. The idea is that we find a host or hostess and we have a promotora (community health educator) go into the home, giving a half-hour session showing flip charts on different kinds of cancers. It's very understandable. The beauty of these sessions is that because they're small (5 to 12 people), friends and neighbors or extended family are invited, and you can answer a lot of questions. These kinds of home health parties are effective for getting people in for breast cancer screening and colorectal cancer screening. We did them around pesticides and diabetes, too.

When did you develop an interest in health disparities?

My initial work was in the area of smoking cessation in the late 1980s. We tried to tackle smoking problems in the communities, being facilitative but not telling them exactly what to do. It was wonderful. It felt natural to continue to work for the underserved, for people who don't have the abilities, the wherewithal, the money, the education, and so forth, to take advantage of what we know in cancer prevention. Disparities in general became my passion.

Some of the many knick-knacks in her office at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

You studied English as an undergrad and then sociology. How did you end up in cancer prevention?

It was mostly serendipity. When I was a graduate student, I was concerned about social problems. My dissertation was on white collar crime. I was already looking out for the underserved – white collar people were taking advantage of people. All I wanted to do was teach and do research at a small, private liberal arts college, but I soon found out that I didn't have any time for research except in the summer. So after three years of teaching, I wanted to do something else. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center had just started their cancer prevention program under Maureen Henderson and they were looking for a senior behavioral scientist. I saw the ad and said, 'Well, I'm not a senior behavioral scientist, but I can do most of the stuff.' They invited me for an interview, and that's how I became a public health person!

What else are you working on besides cancer prevention?

I have a project on diabetes out in the Valley. The interesting thing about that is so many of the ill effects of diabetes are the same as for cancer: diet, physical activity, smoking. We do a lot of education around healthy eating and exercise. Another interesting project is pesticide exposure among children of farmers. I work with Elaine Faustman of the Center for Child Environmental Health Risks Research.

How do pesticides affect our health over the long term?

For children, there are developmental delays, language delays, learning delays. Some kinds of cancer (leukemia, for example) appear to be more prevalent in children of people exposed to pesticides.

Beti Thompson with Matthew "Mateo" Banegas, who received the School's 2012 Gilbert S. Omenn Award

What kind of results have you seen from your research?

It's quite amazing. One of our studies showed that during certain seasons of the year, when farmers take off the blossoms or the small fruits so apples will grow bigger, their rates of pesticide exposure skyrocket – up to 100 times the national sample. As for impact, some of the pesticides used in our first study have now been taken off the market. And we've really made people much more aware of pesticides so that they do things to reduce their risk of exposure, like taking off their shoes before entering the home, washing their clothes after one wearing, taking a shower after coming home. We've seen a lot of changes in behavior.

Are Hispanics/Latinos at greater risk for some diseases?

Actually, it turns out they're not. For many cancers, Latinos have lower incidence rates than non-Hispanic whites. The exception is cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is almost twice as prevalent in Latinos. Diabetes is also almost twice as prevalent in Hispanics. But when you start looking at mortality rates, the numbers shift a little bit.

You're an inspiring mentor. What does it mean to you to develop young scientists?

I've tried hard to get people of underserved status into public health so they can be role models for others down the pike. I've had minority interns for the last 15 years. They come for a summer and work on specific projects. I encourage them to go on to college. We also train postdocs or junior investigators how to do cancer prevention with, rather than to, community people.

Thompson leads an annual winter coat drive for residents of the Yakima Valley

Tell us about the winter coat drive.

As you know, there are many low-income people in the Valley, and the winters are pretty harsh, with lots of snow. Our community director at the Center for Community Health Promotion, Ilda Islas, who was recently killed, was the heart and soul of our operation. She suggested we do a little coat drive. So for the last eight years, we've collected coats from the Seattle area and out in the Valley and distribute them. Last year we had about 540 coats.

What do you like to do when you're not working?

Spend time with my four grandchildren. I also like attending the National Geographic Live! lectures at Benaroya Hall once a month. I don't roller skate or anything (laughs). I like a combination of good fiction and non-fiction, and an airplane book for long-distance travel.

What have you read recently?

I've just finished Garden of the Beast, Erik Larson's book. I really, really enjoyed it. I also recently finished The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which is also a fantastic book. One of my staff members is the sister of the author of The Art of Fielding.

Originally Published: February 2013