Why is war a public health issue?

War is, of course, toxic to health. War produces death, disables people and erodes infrastructure that supports health, yet it is entirely preventable. Public health can serve in a prevention role, not just a cleanup role. We set up refugee camps and clinics, send in vaccination teams and doctors, but we need to do more to prevent conflicts sooner.

How do we prevent armed conflicts?

Armed conflict is a political phenomenon. Politicians decide to use militarism as a solution to problems. Public health needs to step up much earlier when we see militarism running rampant and talk about how to deploy resources differently to achieve peace.

Our government recently passed a trillion-dollar defense budget that included support for Saudi Arabia. Saudi weapons are now being used to bomb poverty-stricken Yemen. One of our bombs was dropped on a school bus carrying 40 children. Public health should be saying, “No, that is not okay.”

Highlights

- Director, Community-Oriented Public Health Practice

- Health Workforce Technical Advisor, Health Alliance International

- PhD, UW School of Public Health, 2003

- MHA, UW School of Public Health, 1983

Do you think speaking up could make a difference?

It has in the past. Public health has taken on big actors who harm health — from fast food and soda, to tobacco and automobile industries. We helped to remove cigarettes from billboards and TV ads, and to design cars with seatbelts and airbags – and it has saved a lot of lives.

What other roles could public health play?

One is to develop the field of conflict epidemiology, an orphan science through which researchers estimate the number of deaths caused by war and identify other causes and consequences of armed conflict. An example is domestic violence. Previous research has shown that more than 1 in 5 incidents of domestic violence were linked to a partner exposed to combat in the military — but we never point this out as a way to prevent domestic violence.

Another is citizen-to-citizen diplomacy. In the wake of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2013, a group of us at SPH formed a relationship with the University of Basrah. We collaborated on a leukemia research project and made trips back and forth to share knowledge. The partnership also created unique student opportunities to engage with war and health.

You led a team to estimate mortality in Iraq after the war. What did you learn?

How hard it is to measure mortality after a war has been underway for so long. By 2011, Iraqi families hit hardest by the conflict had left the country. We have no established methods for estimating that flight — that is, the effect of migration on cluster sampling.

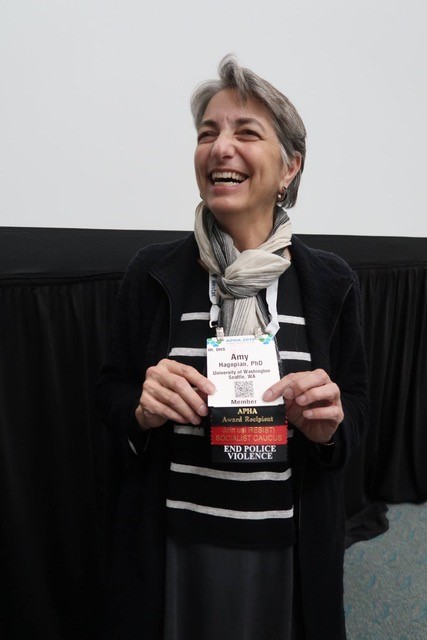

Amy receives the Victor Sidel and Barry Levy Award for Peace.

What methods did you end up using?

We did household surveys to learn who lived in each home before and after the war, and if there were any births or deaths. We wanted to establish death rates to compare to the pre-war rates. We also wanted to know how deaths occurred so we could associate the deaths with war-related causes.

We also asked every adult in each household about their siblings – if they were alive or dead and the cause of death. This is a well-known epidemiologic tool used in low-income countries. We gathered data about the lives and deaths of 25,000 people — even though we interviewed only 5,000.

You were also part of a team that used the New York Times to measure historical war-related deaths in Iraq. Tell us about that.

Former MPH student Shang-Ju Li led that work. He took our pre-2003 invasion mortality data and designed a new method to estimate deaths associated with earlier Iraq wars, from 1980 through 1993. He assessed the reliability of sibling war-related death reports by tracking related news in the New York Times. We searched for articles about events associated with Iraq and Iran for the years of this study and found that an increase in war-related news reports corresponded with an increase in sibling reports of deaths for the same period.

When did you know you wanted to teach about war and health?

I’ve wanted to do it for a long time. I have a great partner in Evan Kanter, who presented at a forum SPH put on when the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003. As a psychiatrist with the Veterans Affairs Hospital, he anticipated the devastating effects of war on U.S. soldiers, including the PTSD and poly-trauma. It was eerie how prescient he was.

WAR AND HEALTH

Hagopian and Kanter teach War and Health during the spring quarter. Students explore the health consequences of war and the role of health professionals and others in preventing war. It's open to undergraduates (HSERV 415, GH 419) for three credits as well as graduate students (HSERV 515, GH 519). Lectures are held Mondays and Wednesdays; graduate students lead small group discussions on Fridays.

How did you develop the course?

Arianna Rubin-Means, who was an SPH doctoral student at the time, helped us design a unique course on the health effects of war that also challenges students to think about the role of public health in interrupting war. We just finished our fourth year of teaching it.

What are some issues students grapple with throughout the course?

Topics include mental health, how structural violence can lead to armed conflict (and the other way around), the environmental impact of war, infectious and chronic diseases, legal issues surrounding war, torture and the effects of various weapons, including nuclear. We even talk about how each war has a signature wound; in the Korean War, it was frostbite.

We provide a menu of 10 or so wars — including the Mexican drug war, Vietnam War and war in Syria — and students choose a “study war” that will be their vehicle for navigating course content. We focus each week on a different topic and students learn about each other’s wars through the weekly topical discussions. Graduate students in the course serve as discussion leaders.

What about the public health portion of the course?

For their final papers, students write about prevention activities that could interrupt their study war. For example, stopping militarism or nationalism in advance, providing relief during wars or doing good epidemiology.

Amy with grandsons Miles and Satchel.

Had you always been interested in war and health?

My interest in war dates back to the 60s when I was a teenager during the American war in Vietnam. I grew up in upstate New York and helped organize anti-war demonstrations. I enjoyed working with people who shared my enthusiasm for changing the world.

Before getting into global health, you worked in rural public health and community development. Why did you transition?

Like war and health, my interest in rural health is about social justice. I helped small, rural health systems strengthen and expand to better serve their communities. When I began my PhD studies, I pivoted my interests to study the global health workforce. My dissertation was on the migration of health workers from poor to rich countries. I graduated from SPH’s inaugural Department of Health Services PhD class in 2003.

Does your family have the same passion for social justice?

Amy with son Jesse and grandson Miles at a gun violence rally.

Social justice is a family business. My father was the son of survivors of the Armenian holocaust at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. My grandparents helped organize the auto workers’ union in Detroit in the 1930s. My dad organized “GIs against the Bomb” after serving in World War II, then got his PhD and became an English professor. My father-in-law was a conscientious objector in World War II, and his son is involved in all kinds of activism. My oldest son, Jesse, teaches at Garfield High School and is doing important national work on racial and social justice. My middle child, Kolya, a psychology grad student in California, is always engaged in good causes. My daughter, Anna, teaches art and rescues animals. She and I work together to offer pet care clinics at Seattle homeless encampments.

How do you feel about receiving this year’s Victor Sidel and Barry Levy Award for Peace?

I'm so thrilled to get this honor from APHA. Nothing could make me happier — except, of course, world peace, or at least stopping the bombing of Yemen. I knew Vic Sidel before he died this year; I’ve worked with Barry Levy as well. They were real pioneers in the field of war and health, and they paved the way for public health workers to consider this part of our mission — and they used good science to do it. They are my heroes.

Where do you see the field going in the next five years?

Amy giving the opening remarks at a recent gathering of war and health experts in Beirut.

This was the focus of a recent gathering at the American University of Beirut. Our vision is to coalesce a new field of war and health research and prevention. We have refugee health and disaster response, but it’s time to go further upstream so we’re not only taking care of victims, but preventing war before it starts. We’re laying out a research agenda and formalizing an organization that would bring together scholars in this field. We’ll hold conferences and produce an academic journal. It’s amazing how many journals there are on urology, yet practically none on war and health. My mission is to help shape this emerging field, and this award certainly helps give it some prestige.

(By Ashlie Chandler)

Originally published: 2018