Abandoned by her mother at age four and emotionally starved until 18, Anne McTiernan overcame adversity and obesity to earn a PhD in epidemiology and an MD in internal medicine. Today, she is a pioneer in women’s health research designing studies that aim to reduce the 25 percent of cancers caused by excess weight and sedentary lifestyles.

You are considered one of the pioneers in women’s health research. What are you most proud of?

I’m happy to have found clues to how we can help people lower their risk for cancer. And I’m especially happy to have shown how simple lifestyle changes can dramatically reduce weight and increase physical activity.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Research Professor, Epidemiology

- Research Professor, Geriatrics

- Full Member, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutch

- MD, Internal Medicine, New York Medical College, 1989

- PhD, Epidemiology, UW, 1982

- BA, Sociology, Boston University, 1974

What is the connection between physical activity and weight loss and the chances of getting cancer?

We know that being overweight and having a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increase in risk for developing certain cancers. Currently, with more than two in three adults considered to be overweight or obese in the U.S., understanding the reasons for this increased cancer risk is critical. Nothing is guaranteed, but exercise and weight control are like wearing a seat belt—they reduce your risk.

Risk reduction is difficult to quantify. How do you gauge it?

By measuring biomarkers in our research participants. For example, we think that one way obesity increases risk for breast cancer is through hormones. After menopause, women with obesity tend to produce high levels of estrogen in their fat cells. That estrogen gets into the bloodstream, goes to the breast and can cause a cancer to develop.

When we got women who were overweight or obese to lose just 5 to 10 percent of their starting weight, we saw their blood estrogen levels drop significantly after one year. We estimated that reducing weight by that amount, a woman’s chance of developing breast cancer would decrease by 22 percent. One in five breast cancers could be prevented.

Anne McTiernan and her husband,

Martin Tompa, UW professor of computer science & engineering

You also studied the effects of diet and exercise on oxidative stress. What is oxidative stress and why is it important?

Oxidative stress is a relatively unexplored mechanism that could link obesity with cancer risk. It results from an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the ability of the body to detoxify their harmful effects. We think that oxidative stress could damage DNA and begin the process of carcinogenesis, or cancer formation.

What did you learn from this research?

That changing women’s diet to reduced calorie, reduced fat—with a goal of losing 10 percent of their starting weight over one year—significantly reduced levels of two compounds associated with cancer risk. The findings from our studies suggest that it’s never too late to make lifestyle changes to lower risk for cancer.

What do you do to stay active?

I walk with friends every morning. We have a set time, so I know I have to get up in time to do that. I also get on the stationary bike and read, sometimes it’s work reading and sometimes it’s fun reading, but it’s a nice reading time. My husband and I also like to go hiking.

You recently published a memoir that chronicles your journey to adulthood and your tumultuous relationship with food. Did you get into this field of research deliberately based on past experiences?

Some of it was just by chance, like the Women’s Health Initiative, which I got involved with when I first came to Fred Hutch. But some of it was deliberate. I feel like I understand what a lot of our study participants are going through. I know what they are dealing with when they talk about not wanting to give up a food or an eating behavior. I absolutely empathize with them.

I gravitated toward exercise and weight control because we have such an epidemic of obesity and a crippling lack of exercise and healthy eating. I know that my research can make a significant impact.

What stories do you tell in your book?

The book begins in the 1950s. I was four years old when my mother first dropped me off at a Catholic boarding school outside Boston, in Watertown. My mother was a single mother. My father had left before I was born. And I was left on my own at a young age, at this school, from Monday through Friday. I was emotionally starved. As a result, I stopped eating and starved myself. Our family doctor recognized how unhealthy I was and told my mother to take me home. Professionals call it a “failure to thrive.”

At age 7

Anne as a toddler

What happened after you were removed from boarding school?

More than a decade of physical and emotional abuse followed, as did a vicious cycle of food and body-image issues. I was dealing with a mother who didn’t give me emotional nourishment, so I overate and became obese. In high school, the holy grail for me was getting a boyfriend. I thought that he, whoever he was, could save me. I started obsessively dieting in order to lose weight and attract the attention of boys. It really wasn’t until I moved away from my mother’s house that I started my healing process.

How has the adversity you faced as a child impacted your work?

It molded me into a better researcher. You have to be very persistent in research, especially as a woman and especially back when I started in the early ‘80s. Nailing down grant funding is extremely difficult when you’re starting out. It’s one thing that pushes people in my field to look for careers outside of research.

Why did you decide to write about these personal experiences?

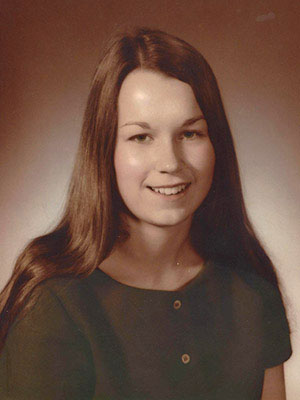

Anne at 17

An awful lot of people are dealing with overweight and obesity, not only here in the U.S., but also globally. It’s useful for people to see that an experienced researcher in this field has also dealt with similar issues. I thought it would be valuable to share my experiences. Plus, I was reading a lot of memoirs and really enjoyed them. In particular, Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt. He wrote about a miserable Irish childhood and I thought to myself, Hey, I had a miserable Irish-American childhood. I could write a book.

(By Ashlie Chandler)

Originally published: January 2017