Heroin use is on the rise across Washington state, with the most dramatic increase among 18- to 29-year-olds. Caleb Banta-Green tracks these trends and more. Find out what he has to say about heroin, marijuana and the need to change the dialogue around medication use.

Where did you grow up?

A block from the Montlake Bridge. My Dad was a neurologist at the UW and very involved in some of the free medical clinics – including one for the Black Panthers – that started in the 1960s. I sort of have that community-service orientation. He died when I was three. My Mom worked in neurology, editing a medical journal. I was raised hanging out on South Campus, although I still can't find my way anywhere.

When did you first realize you had a passion for public health?

I was studying biology-immunology as an undergrad at UC-Santa Cruz and learned about public health during my last year. There was a course on how race and gender impact health, and that's where I realized, "Ohhh, I'm a public health guy!"

At a Sounders game with wife Kate and sons Pete and Bobby.

When did you come back to Seattle and the UW?

In 1993. I started volunteering with the AIDS Prevention Project at Public Health – Seattle & King County. Then I got a job with Planned Parenthood as a health educator/nursing assistant and applied to Social Work School at the UW. I also applied to the School of Public Health, and did a joint MSW/MPH.

How did you develop an expertise in drug use?

My first internship was probably my last choice – a methadone maintenance clinic, working with heroin users. I still see myself as a public health/health behaviors guy; I don't see myself as an addiction guy. But that happens to be where my research area has flowered.

What did you learn about heroin?

What stuck with me was how strong a hook it puts in you, and how complex it is for people to make healthy choices and set up a healthy environment for themselves. It hijacks the brains primary reward systems. The story I often tell is of a client saying to me, "Oh, I was talking to my girlfriend last night, and we both agreed that we loved heroin more than each other."

What does your most recent drug abuse report tell us?

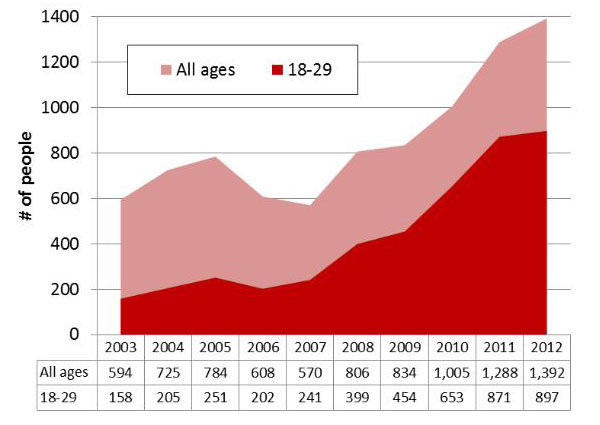

Everything's decreasing except heroin use among 18- to 29-year-olds. The number of opiate-involved deaths (both for prescription pain medicine and heroin) doubled over the last decade, increasing geographically across the state. There's also been a dramatic increase in the number of people coming in for treatment the first time for whom their primary drug is heroin, from 600 in 2003 to 1,400 in 2012.

Why is heroin on the rise?

Prescription-type opiates and heroin are basically the same biochemically. With the reining-in of opiate prescriptions starting in 2008, people who were abusing drugs obtained from the black market can't get them anymore. Everyone was surprised that people would go from pills to heroin. To me, it makes perfect sense. You're abusing prescription pain pills, snorting or shooting them, you need more to get the same effect, you can't find pills easily and heroin's cheaper and widely available.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Affiliate Assistant Professor, Health Systems and Population Health

- PhD, Health Services Research, UW

- MPH, MSW, UW

- BA, Biology, Santa Cruz

- Science Adviser, Executive Office of the President, 2012

- Runs stopoverdose.org

Where's the heroin coming from?

All of the heroin in our state comes from Mexico. It's black tar – a raw, pretty unprocessed product. It's very low purity and to get a good high from it, most people end up injecting it.

How do you track drug trends?

Drug use is a hidden phenomenon, so you rely on lots of different measures that tell you different parts of the story. Drug-treatment admissions. Fatal overdoses. The State Department of Health gives some of the data, as do medical examiners. Some comes from the state toxicology lab of the state patrol – a novel data source. This is what the police are getting off the street. It's totally imperfect, but it tells you something profound. I get real-time data, and I'm trying to get county-level data in the hands of county-level people because that's where the decisions get made. I also help devise questions for surveys so we can better measure things, whether it's the King County syringe exchange survey or the state adolescent survey.

How did you end up as a science adviser at the White House's drug policy office last year?

The director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (aka the drug czar) was out in Seattle for a meeting, and I asked someone in his office if I could have 15 minutes with him to talk about our overdose research. At the end of that meeting, he asked if I would be interested in a sabbatical and coming out and being a science adviser in the Executive Office of the President. At first I said, "No thank you, I just got a big grant," but then I thought about it and realized it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to impact national policy. I worked half-time for half a year out there on a very focused project on overdose prevention.

I WAS RAISED HANGING OUT ON UW'S SOUTH CAMPUS, ALTHOUGH I STILL CAN'T FIND MY WAY ANYWHERE.

Do you feel you had an impact on policy?

Yes. When the president's drug strategy came out this year in April, it had a bunch about overdose prevention for the first time. When I was in DC, I did a lot of training and education with staff so that when I left, the knowledge didn't. I continue to remain in contact with people in the DC office and am happy that the director's new, more public health approach continues to get implemented.

Tell us about the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute – you're not part of any school or department?

We're under Health Sciences Administration. We're not department affiliated, and that's purposeful. It's to keep it very interdisciplinary. My formal ties with the School of Public Health are fairly recent – a year, year and a half, though I've worked with students for years. I'm also increasingly collaborating with the Harborview Injury Prevention Research Center. Drug poisoning is the number one cause of unintentional injury death now; it has surpassed motor vehicle fatalities. People don't think of addiction as a public health topic. They think of it as a moral failure or maybe as "behavioral" health. They only think of it as public health in terms of the consequences of infectious disease or injury. No one's running out to embrace this population or this topic.

What kind of public health approach is needed?

Think about all that we do for traffic injuries – the law, the educational messaging, behavior modeling, the structural interventions. We don't have the same approach for substance abuse. I think we need to really think differently about how we communicate as a society, as parents, as medical providers, as public health, about health, stress and anxiety and how we use psychoactive substances to medicate those. Marijuana is the perfect example. It's illegal, it's legal and it's a medicine – all at the same time. Approaching it from any one of those perspectives is useless. People take marijuana for a range of reasons – for fun, for medical conditions, for stress release, because they're addicted. I could say the same thing about alcohol, opiate pain medicines, tobacco. You can't prevent drug abuse with youth without starting when they are very young and actively involving their parents.

Being healthy is simple, but it's not easy. But, if you believed all of the advertising that pervades our society, you'd that think that being healthy is easy. In fact, you'd think you could be healthy by being inactive and passive and that you could deal with stressors in life by reaching for a bottle (of any kind) or a diet chocolate cake. Public health has made some progress in the area of childhood obesity and it'd be terrific if young public health researchers could start thinking about what are the population level interventions for substance misuse prevention (whatever the substance might be).

FIRST-TIME HEROIN TREATMENT ADMISSIONS IN WA STATE

Banta-Green's reports get data into the hands of local public health officials. This graph shows a dramatic rise in first-time treatment admissions for heroin in WA state.

Are you concerned about marijuana use?

I do think marijuana is a big deal from a public health perspective. I don't think young people should use it. I don't think it's healthy or safe. It's not a benign substance. It has psychotropic (mood-altering) effects. I'm also concerned that we are going to just extend existing approaches, for instance tobacco prevention and cessation, to marijuana. Tobacco approaches are not going to work for marijuana. Perceptions of risk, correctly, are lower for marijuana compared to tobacco. Marijuana's health and behavioral impacts can be subtle and when used in moderation there may be no adverse health impacts. To me marijuana represents a gateway into a new type of a conversation. Why do we take substances? How do all of the various psychoactive substances I ingest interact with each other? Are we honest with ourselves about why we use? Are we honest with others? Are we sending the messages to our kids that we want to be sending?

Caleb during a Cyclocross race in Roslyn, WA. Photo: Pete Banta-Green

Tell us about your new grant.

I received my first big five-year grant from the NIH in 2012 for about $2 million to develop and test an overdose prevention intervention at Harborview. We're working with both heroin users and prescription opiate users at risk for overdose. We're combining overdose education with brief behavior-change counseling to see if we can reduce overdose occurrence, overdose risk behaviors, HIV risk behaviors, and inappropriate medical care use. It's very, very exciting. As you know, in my line of work as a research scientist, getting a five-year NIH grant is like getting your first book contract.

What do you do for fun?

Play sports with my kids (ages 9 and 13). Camping and exploring the Seattle area with my family. I like Cyclocross racing. It's half-road bike, half-mountain bike, and you loop through a two-mile course on mud and dirt, sand and gravel. I like cooking when I can. I just taught my 13-year-old how to cook lasagna.

What do you tell your kids about drugs?

I tell them people use drugs because it feels good at first, but for those who become addicted they end up using drugs to not feel bad. We talk about the things they get happiness from and making sure they are physically active. We try to impress upon them that dealing with stress is a lifelong challenge and we're trying to help them fill up their toolkit with a range of stress-relieving tools.

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally Published: September 2013