Evan Gallagher tried a variety jobs after college, including playing guitar for touring rock bands. Then he found a niche in environmental toxicology – studying the effects of environmental chemicals. Now, he has become an expert on cells in the tiny noses of salmon, trying to understand how chemicals affect the ability of salmon to locate predators, prey and migrate home. This work can help determine if Superfund sites really are safe for fish such as salmon after site cleanup, and whether other waterways might pose a hazard.

What chemicals are getting into our fish?

No matter where you go, you can detect some type of chemicals in fish. It doesn't mean the fish are unhealthy, or unsafe to eat. The chemical residues vary in the amounts and with location. For example, some fish in our regional Superfund sites (Duwamish waterway in Seattle, or Commencement Bay in Tacoma) contain PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), metals, and other chemicals. These can come from industrial sources or runoff. It also depends on the species. Some fish migrate through the area (like salmon) or live in the site year-round near the sediments. If you go to an agricultural drainage, you may find fish with some pesticide residues. In some situations, effluents from wastewater treatment plants may leach chemicals called "emerging contaminants."

Are these emerging contaminants chemicals that have flushed through our bodies?

In some cases, yes. They include things not previously detected in the environment such as antibiotics, estradiol (for birth control), caffeine, ibuprofen and some personal care products. But I want to be very careful: just because these products are getting out there doesn't mean they are posing a risk to fish. The chemicals that are known to interfere with fish olfactory processes – their sense of smell – are metals such as cadmium, copper and certain pesticides. We are studying if other chemicals pose threats.

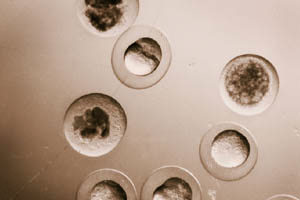

Evan Gallagher's lab research involves zebrafish embryos

Where does the copper come from?

Some of it can be from natural sources, also mining and industry. Locally, a lot appears to be coming from brake linings as they shed while we drive. Cadmium comes from a number of similar sources, and industrial processes such as electroplating can be sources.

How are fish affected?

Relatively low levels of these metals and pesticides block the ability of fish to detect predators and prey and find their way back to natal streams. All fish rely on chemical cues in the environment. Salmon, we think, are disproportionately at risk because they rely so much on proper olfaction. They have a nose for all these processes.

What is the aim and potential impact of your research?

A big unknown is what's happening on the cellular, molecular and biochemical levels: What sensitive biomarkers could be used to detect if salmon are having a problem with olfaction because they're in this polluted water? It would help to show which waterways might be polluted or whether certain salmon are at risk. Or in the case of Superfund, where millions of dollars might be spent on cleaning up a site, we could go in afterwards and say whether salmon are doing well or not.

Looking at transgenic zebrafish with PhD student Andrew Yeh

(Courtesy of Washington Sea Grant)

Tell us about your research on flame retardants.

There are different flame retardants in our houses to keep things from catching fire. We are studying PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl ethers), and because our chemistry techniques are so sensitive, we can measure these just about everywhere. There's been some concern of PBDEs showing up in some salmon. We are studying what this means for the salmon, and for us, with funding from Washington Sea Grant.

How can flame retardants possibly get into our fish?

The PBDEs are outlawed now, but they're very long-lived and they're not chemically bound to the materials they coat. They've been in consumer products, cushions, sofas, building materials, clothing. There's some debate on all the sources: Leaching from landfills, runoffs, probably past inappropriate recycling, and atmospheric transport. A small group of Chinook blackmouth from some areas of the Puget Sound that do not migrate to the open ocean have higher levels than other salmon. It has raised some concern.

We love our salmon. How safe are they to eat?

It's my opinion that our salmon are overwhelmingly beneficial for us, especially in the Puget Sound region. They have all of the things you find in vitamins and supplements – Vitamin E, antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids – that protect against heart disease, age-related disorders. Some salmon have elevated levels of PBDEs, but we haven't established the risk. Since we can't experiment on humans, we're doing some research on zebrafish to provide more science.

How did you get interested in toxicology?

I bounced around in different jobs after college. I worked as a field biologist. I worked as a professional guitarist for several years back in the '70s. I considered a career in music, but that was pretty risky. I realized I needed to go back to school, and took a course in environmental toxicology. At that time, in the '80s, it was a new and growing field. I'm an environmental person at heart and I'm also real curious about pollution. If chemicals were dumped into a waterway, where do they go? What are the effects? Toxicology is really interdisciplinary. It brings in biochemistry and ecology and that really spoke to me. I was very fortunate. It's tough to figure out directions. It took me several years to figure it out.

With PhD student David Scoville at the Center for Ecogenetics and Environmental Health annual retreat

You were tenured at the University of Florida. Why did you come to the UW?

Things were going very well in Florida, but I had a longing to return to the Northwest, where I did my postdoc in the School of Public Health. I also saw a niche for an environmental toxicologist with my approaches to contribute to unique natural resource/human health issues of the Northwest. Certainly, part of it was my interest in the Pacific Northwest, the culture, outdoors and fly-fishing. It was one of those life decisions. We can stay put and be safe, or take the risk and try something new.

You recently took a sabbatical in New Zealand and Australia. How was it?

It was a great experience. It was six months – I should've taken a year! The first part was in New Zealand at the Cawthron Institute, a private interdisciplinary institute where I spent about four months as a visiting scientist. In Australia, I received a Distinguished Visiting Scientist Award to work with the national laboratory on how we can develop biomarkers to help assess the tremendous impacts from mining and coastal development on the Great Barrier Reef.

What will you remember most?

Just interacting with the people and scientists. They have a good outlook on life. They balance family, their work and their outdoor activities like I've never seen – certainly better than this country. At tea breaks, they get away from their science and talk about other activities, and there was a lot of intellectual discussion about the nature of education. At the end of the day, you're not any less productive.

With partner Yanyu on the South Island of New Zealand

Speaking of work-life balance, what do you do for fun?

Fly-fishing during the summer months. The Yakima River is our favorite spot. I still play some guitar, not as much as I used to. Those are probably my main passions along with wine. My partner Yanyu, who works at Seattle Genetics, and I like to try new restaurants with friends. Friends are really extended family.

You have a patent on a prosthetic for playing the guitar?

I've been an amputee since birth but I've always been fierce at attempting new things. When I was about 16, my mom and I visited a woman who worked with amputees to play musical instruments. We worked with a local dentist who made a mold of my arm with a pick and a Velcro holder, and that's what we patented. We thought there might be a time later in my life when I could give back to veterans and others. It wasn't about making money. When I was in grad school at Duke, there was a renowned guy in prosthetics who helped me develop a much more sophisticated device that I use now.

Do you still play in a band?

Not now. Work as a professor is too demanding. If I ever go part-time or win the lottery, I'd like to devote more time to that.

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally Published: Dec 2012