Transmission of HIV from mothers to children has dropped dramatically, thanks to researchers such as Grace John-Stewart. Find out how success in Kenya led John-Stewart to create a UW center that integrates public health approaches for women, children and adolescents.

What motivated you to go into global health?

My grandfather founded a number of leprosy hospitals in India. My parents were physicians who trained in the US and went back to India to work in mission hospitals. Growing up here and in south India (in Kerala), I could see the impact my parents had. I wanted to work with people who didn't have access to doctors.

In Kenya with a colleague's children, Nyambura Ngacha and Christopher Nyange

Why choose the UW?

After studying medicine and pediatrics, someone told me about the University of Washington, and I came out here to look at the infectious diseases program. I met Joan Kreiss [former epidemiology professor], who was doing a really important and interesting study in Kenya to see if breast feeding transmitted HIV. That sounded appealing.

So you ended up in Kenya?

It was supposed to be for a year, but I ended up staying about 12 years! It was 1993, and we were just beginning to understand how widespread the HIV epidemic was. About one in seven women in Nairobi had HIV. They were usually young and it was their first pregnancy. It was totally unexpected.

Tell us about your research there.

We followed these women and then their children to try and understand how transmission occurred. Over time, as we and other groups learned more, it was clear you could stop transmission if you treated the mothers. At the beginning of our work, there was a 30 percent chance that a women would transmit HIV to her baby. By the end, it was maybe 1 percent. It was really rewarding to be part of that.

Highlights

- Professor, Epidemiology, Global Health, Pediatrics, Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- PhD, Epidemiology, UW, 2000

- MPH, UW, 1995

- MD, University of Michigan, 1987

- Elizabeth Glaser Scientist Award

- UW Medicine Mentoring award

- Director, CFAR International Core, Kenya Research Program

Was that mostly because of ARV (antiretroviral therapy, a combination of drugs that slows down HIV)?

It's all ARV. HIV can be transmitted through the placenta, birth canal or breast feeding. All three time points for entry can be prevented with ARV. After that initial research, we moved from how transmission occurred to "What do you do to scale this up?"

How did your experience influence the UW's Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents and Children (Global WACh)?

We found in our research that we were trying to improve outcomes both for mothers and their children simultaneously and that there was a benefit from doing this. Our model was to look at women and children concurrently and it became the foundation for Global WACh, which is about the life cycle. Initially, we were following all of these women to prevent their children from getting HIV, but then we had to pause and say, "Well, what about the women themselves? What about their health?" There's also a growing appreciation that adolescents are a distinct group. There are a lot of teen pregnancies, a lot of issues in teen motherhood. Fred Rivara and the Chairs of the Departments of Global Health, Pediatrics and Obstetrics/Gynecology encouraged us to use our experience in mother-child HIV models to develop a center looking across the life cycle.

Can you give examples of the life cycle?

In-utero health has a long-term impact on the health of the child/future adult. Maternal mental health issues could have long-term impact not only on the mother and her child-rearing ability but also on the child long-term. Strategies addressing reproductive health in adolescents would affect their future motherhood or their child-rearing practices. The life cycle tries to think about more than one of the three groups. We try to avoid silos and think in a more integrative manner. It's easier said than done.

SOMEONE TOLD ME THEY CRIED WHEN THEY FOUND OUT THEIR KID DIDN'T HAVE HIV, BECAUSE THEY WOULDN'T GET THE SOCIAL SUPPORT, THE NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT.

Can you provide a brief overview of how the Center works?

It's young – just two years old – and part of three departments: global health, pediatrics and obstetrics. It started as a request for Center proposals and we were very fortunate to be selected. The Chairs provide oversight and meet with us to help us see areas of synergy and needs for long-term development. Initially, we wondered how similar the visions of the three Chairs would be for the new Center and how we would balance competing priorities – but the input from all three has been pretty aligned. More than 200 people are affiliated with the Center. I'm the director and Maneesh Batra and Dilys Walker are co-directors. We have an Executive Committee with members from all three parent Departments. Besides bringing that vision of the life cycle, one of our goals was to be aggressively interdisciplinary. So we've linked with the UW Bioengineering to see if there are technical innovations that can improve WACh health and with the Law School to bring lawyers, policymakers and health people together to ask how to address women, children and adolescent health with different frames.

With husband Mark and their daughter, Hannah

What are your most exciting projects?

We've given several seed grants. Deepa Rao looked at depression in India and maternal health. Scott McClelland has tried to figure out if he can get into adolescent populations to screen for STIs. Dilys Walker and her colleagues looked at video-game strategies to help traditional birth attendants make better decisions for women and children during the delivery process.

Another project led by Lisa Frenkel, Barry Lutz and James Lai links bioengineers and clinicians. Current tests for resistance to ARV drugs cost $500 to $600, which is beyond the means of most resource-poor settings. This group has developed strategies for point-of-care testing that may bring that cost down to $10 or $30 – something portable that doesn't require a lab. That, in turn, would buy back so much value in preserving drug regimens.

What other kinds of research are you doing?

One of our ongoing studies asks how you can prevent pregnant women from getting HIV. We're also trying to figure out if we can test children at home. Three million children have HIV (90 percent of them in Africa). If infected early, they have a high mortality rate. Often children slip through the cracks. Can we detect their infection and treat them early? Can we accelerate their treatment if they are hospitalized? Disclosure is another issue. A lot of parents don't want to tell their children they have HIV. No one wants to give a kid bad news. There's never a good time for disclosure, but it's an area we're trying to evaluate.

What about non-HIV issues?

There's been a lot of appropriate investment in HIV, but in the very same places you actually see a lot of preventable disease – kids dying from diarrhea, for instance. A couple of years back, someone told me they cried when they found out their kid didn't have HIV, because they wouldn't get the social support, the nutritional support. There's a funny sort of imbalance. So within some of our studies we're trying to see what can we do to help children with other outcomes, such as respiratory disease, diarrhea, stunting.

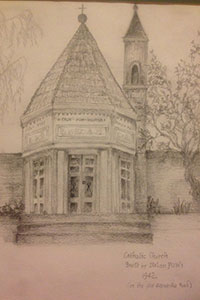

John-Stewart's sketch of the Italian chapel built by POWs on Old Naivasha Road in Kenya

You've been honored by the UW for mentoring students. What does that mean to you?

I was fortunate to have good mentors. I find it a privilege to work with emerging investigators and leaders – to be part of how they transition into their ultimate expertise and to watch as they develop new directions. You learn as much from your trainees. It's a good feedback loop – both in Kenya and here.

How much time do you spend in Kenya nowadays?

Maybe six weeks a year, spread over several short visits. But I'm in touch every day. It's still like being there - although I often miss being there full-time.

What do you do for fun?

I like sketching and drawing, music and reading, church activities, hanging out with family. I have a 12-year-old daughter and a husband who works with an NGO in West Africa. Sometimes I go with him. We share that heart for those kind of activities. Being a parent is a great joy.

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally published: August 2013