Seconds count during a heart attack. But many people don't recognize the symptoms or they wait too long to call 911. Even cultural issues can get in the way. Hendrika Meischke and her colleagues at the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice have been working with dispatchers, emergency responders and the public to change that, and save more lives.

What work are you most proud of?

The heart attack survival kit project, which ran from 2000 to 2004. More than 300 firefighters were trained by our research staff to go door-to-door to educate seniors about the signs and symptoms of heart attacks and to encourage them to call 911 and take quick action. Your heart muscle dies with every hour that you don't do anything. We have 30 fire districts in King County and they all participated. They reached 25,000 seniors in their homes, and it was just an incredible effort. We found that 18 percent more people called 911 to report chest pain.

What are you working on now?

We're studying the communication processes between 911 dispatchers and the public, especially callers with limited English. Dispatchers need to know within seconds whom to dispatch and where to send people – and that's really challenging when you have language barriers. The fundamental thing that causes a lot of delays is the address. Without an address, dispatchers cannot send anybody. If you don't know where you are, or you don't know your street or your home number or you apartment number, it takes that much longer.

People don't know where they live?

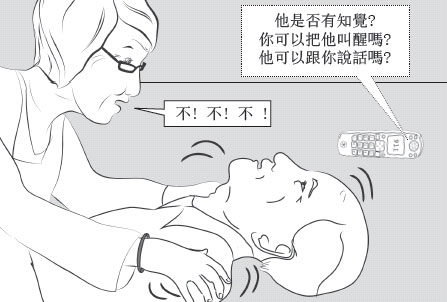

A page from an emergency graphic novella in Chinese

They might, but they can't say it in English. Sometimes it's a relative who's calling. Sometimes an interpreter, living outside of King County, WA, is confused about the geographical names of places here. The other issue is that people get frustrated because they think, "Why are you asking me all these questions? I need somebody to come help me." They don't realize that help is already on the way.

What cultural issues arise when dispatchers give CPR instructions?

Some people fear they're going to hurt the patient. In our simulation studies, we see participants being too gentle with the mannequins rather than doing hard and fast compressions on the chest. Yes, you could hurt a person or break a rib, but it doesn't compare to losing a life. We're submitting a grant proposal to develop more culturally tailored outreach materials for Chinese speakers [both Mandarin and Cantonese] and Spanish speakers. Right now, we're testing a graphic novella for Chinese speakers.

What's the storyline?

It's about an older man who collapses, and a woman who remembers a discussion with her grandson about what to do. He's in medical school. We get around the cultural issues with flashbacks to this younger-generation person who is assisting the grandmother. She calls 911 and asks for an interpreter and does compression-only CPR.

You're also training dispatchers. What can be improved?

In about half the cases of cardiac arrest, the patient seems to be gasping or making snoring types of sounds. But they're not really breathing. Both the call receiver and the bystander can get confused by that. Those sounds are cues to say, "OK, this isn't normal breathing. Let's go for it. Let's do CPR."

Hendrika, center, with colleagues Becca Calhoun and Devora Eisenberg Chavez, practicing CPR on a mannequin

What's it like to be a dispatcher?

I cannot imagine doing that job. They're my heroes. Just about anything can come in: People may call and say, "Something's going on in the local park," or "My husband's trying to kill me and I'm locked in my bathroom." You have to deal with the caller's emotions and figure out what's going on and try to get an address. A lot of communication needs to happen very quickly. I'm just awed, honestly, by individuals who can do this day in, day out.

What drew you to this field?

It was the best field to study with my background, as a foreign student. I did my master's in public health in family planning and health promotion, and really wanted to develop family planning campaigns in developing countries. I went on to get a PhD in mass communication. However, my spouse was not ready to go overseas. He was a research scientist. So I got a job here at the UW – 20 years ago – and I was hired into several projects. One of them was at King County EMS (Emergency Medical Services) with Mickey Eisenberg on public education for heart attack symptoms. I've never regretted it.

What brought you to the US?

School. After high school in Holland, I had to wait to get into college because of the lottery system. I met an exchange student from River Falls, WI – a tiny, tiny place – and she talked me into going to school over there at a branch of the University of Wisconsin. I majored in sociology and met my husband in college.

What do you like to do outside of work?

Hendrika (right) with husband Bryce Sopher and daughter Louisa Sopher at the San Francisco Zoo. Son Arend Sopher took the photo.

I walk at least three miles a day. I hate driving. I walk to work from my home in Ravenna. I walk to the store, which helps limit my purchases (laughs). I walk to the parks with my husband. I love walking to the Calvary Cemetery with my neighbor and friend. We study the tombstones. Also, my daughter and I love the Woodland Park Zoo. Every quarter, we pick a day when it's cloudy or there's ugly weather, so the zoo is ours. It's so tranquil. I'm also working on a pea patch in my backyard.

Do you have time to read?

I read short stories, mostly Dutch. I like Sylvia Witteman, a transplant from Holland to the US who writes for the Dutch newspapers. She writes cultural-encounter stories I can really relate to.

Do you miss Holland?

It's been 30 years, but sure. I hate to fly, so I don't go back unless I have to. My father passed away recently. My mother and sister visit me every year. I miss the language, and its playfulness. I've never really mastered English the way I mastered Dutch.

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally Published: September 2012