Before he earned his MD, Joel Kaufman was a best-selling author — for a week, at least.

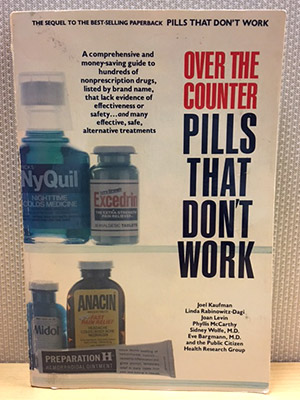

In 1982, he took a year off from his studies to work for the consumer advocacy Public Citizen Health Research Group in Washington, D.C. The result was a book, Over the Counter Pills That Don’t Work.

It was, according to a blurb on the book’s cover, “A comprehensive and money-saving guide to hundreds of nonprescription drugs, listed by brand name, containing ingredients that lack evidence of effectiveness or safety … and many effective, safe, and alternative treatments.”

Pantheon Books picked up the volume—a combination of critique of Food and Drug Administration regulatory lapses around nonprescription drugs and how-to consumer guide—after it was initially self-published, and Kaufman and colleagues spent a week on the New York Times’ best-seller list.

Then it was back to medical school.

Kaufman was 17 when he got into a combined program at the University of Michigan that allowed him to earn his BA and MD in a six-year curriculum. Before long, he was taking public health classes and finding his passion for the health of populations rather than individuals.

“I was interested in health and social justice, and public health was the natural intersection between those,” Kaufman says.

A course on Health and Poverty and meeting the health and safety staff at the United Auto Workers got him thinking about the role of social movements in empowering people to improve their lives and their health.

Cross-country skiing with son Eli, daughter Mara, and Anna

“The labor movement in that period was organizing around health and safety on the job, and pulling scientists and policymakers along, and that’s what drew me into occupational safety and health as a discipline,” says Kaufman, a long-time University of Washington faculty member who was recently appointed interim dean of the School of Public Health.

Kaufman has been connected with the School since 1988, when he came to Seattle to pursue a fellowship in occupational and environmental medicine and to study for an MPH.

He spent seven years with the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries when it developed the SHARP research program, while maintaining a clinical appointment at the UW. In 1997, he joined the faculty full time in Environmental Health (now Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences), conducting occupational asthma research, but increasingly interested in cardiovascular health.

Kaufman later joined a research center that focused on particulate matter air pollution. Today, he’s an internationally known scholar on the connections between air pollution and cardiovascular disease. His work has formed key parts of the understanding that breathing air pollution is a major global contributor to heart disease.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Professor, Epidemiology, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, and General Internal Medicine

- Former chair, SPH Faculty Council

- PI, MESA Air Study

- Author, 2016 Lancet study

According to Kaufman, many people believe that heart disease is under an individual’s control, and that “if you just got it together and ate better and took care of yourself and exercised more, you’re good.”

But it’s not that simple, he says.

“The truth is that even for those factors, there are large social and commercial pressures for people to behave the way they do when it comes to diet, exercise and smoking. In addition, there is a set of factors that people have no control over at all: air pollution, the social environment in which they live, their economic circumstances. These are often not included in peoples’ thinking about causes — and it's why public health scientists and practitioners are the key to prevention of heart disease."

The interim dean adds, “The science that we’re doing on environmental factors in disease is often made more relevant by an ongoing active environmental movement that’s interested in these issues and advocating for science-based public policy changes.” Again, he notes, the intersection between public health and social movements is important.

Kaufman, who took the reins from the former dean, Howard Frumkin, in September, does not consider himself a “caretaker” dean. He expects to be in the post for up to two years before a permanent dean is in place.

The plan is to continue in the same overall direction while “reinforcing our strong foundations that make this School outstanding,” he says. That means maintaining a balance between the scientific disciplines such as biostatistics, epidemiology, exposure sciences, outcomes research and toxicology on one hand, and the multidisciplinary and topically oriented fields such as nutritional sciences, global health, public health genetics, public health practice and health administration on the other hand.

A selfie with daughter, Mara Wald, last spring at Yosemite National Park

“All of these activities are required to be a great school,” says Kaufman, who stresses that the UW SPH is “a top-tier school by any measure.”

The School’s strategic plan remains in place. Its mission is centered on the core activities of research, education and service, and it identifies emerging challenges such as climate change, obesity and implementation science. “The School has made a commitment to these areas with new hires and allocation of resources and we have no intention of modifying those commitments,” Kaufman says.

Among his priorities are seeking sustainable funding, building morale and “redoubling our efforts at diversity, equity and inclusion in all aspects of our School’s activities,” he says.

Despite his new workload, Kaufman maintains a primary care practice with UW Medicine—something he’s done since 1988—helping patients through the regular range of issues such as hypertension, diabetes and cancer screenings. “It’s a different kind of connection with people and uses a different part of my brain,” he says. “I enjoy the personal interaction and trying to understand and help patients one-on-one – even if it seems far from the public health message.”

He has scaled down his practice to a half day every other week, but continues his research program, including mentoring students and post-docs. In 2015, he was named Outstanding Faculty Mentor by the School’s Student Public Health Association.

The UW’s Population Health Initiative and a major gift from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to boost that effort through a facility that will foster collaborations “is setting the stage for a very exciting future for the School,” the interim dean says.

With family (including Anna’s cousin and uncle from Warsaw) on Orcas Island, where the family has a cabin

On the personal side, Kaufman has been married to Anna Wald, a faculty member in epidemiology and infectious diseases, for 26 years. They have a close-knit family and have had four children; the oldest was killed at the age of eight, during a family trip to the Oregon coast. “It’s a defining feature of our lives,” Kaufman says. “Joshua’s death was a huge, life-changing event and ends up being a focal point to our existence on a daily basis.”

His surviving children are now 22, 17, 14 – the two youngest are in high school and the oldest, who just graduated from college, is currently traveling in South America.

The family cherishes getaways to their Orcas Island cabin. In addition, Kaufman is an avid (if fair-weather) cyclist who pedals to work from his home in Madrona. For five of the last six summers, he’s taken part in an organized ride from Seattle to Vancouver, B.C.

One pastime he misses dearly? “I used to have tickets for the Supersonics,” Kaufman says. “I lamented their move to Oklahoma City. I still hope a team lands back here.”

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally published: December 2016