You hold eight patents. Do you consider yourself an inventor?

I’d rather think of myself as an innovator. Inventors create things, but innovators come up with whole new ways of thinking about problems.

Tell us about the spectrometer you invented.

The OP-FTIR (Open-Path Fourier Transform Infrared) spectrometer is an optical technique that uses the rotational and vibrational modes of molecules to identify them. It is a little like a fingerprint of a chemical. It allows remote sensing (in situ) of chemicals over a big area, like a field, factory or pond, by probing the area with a light beam. It can very precisely identify what contaminants are out there.

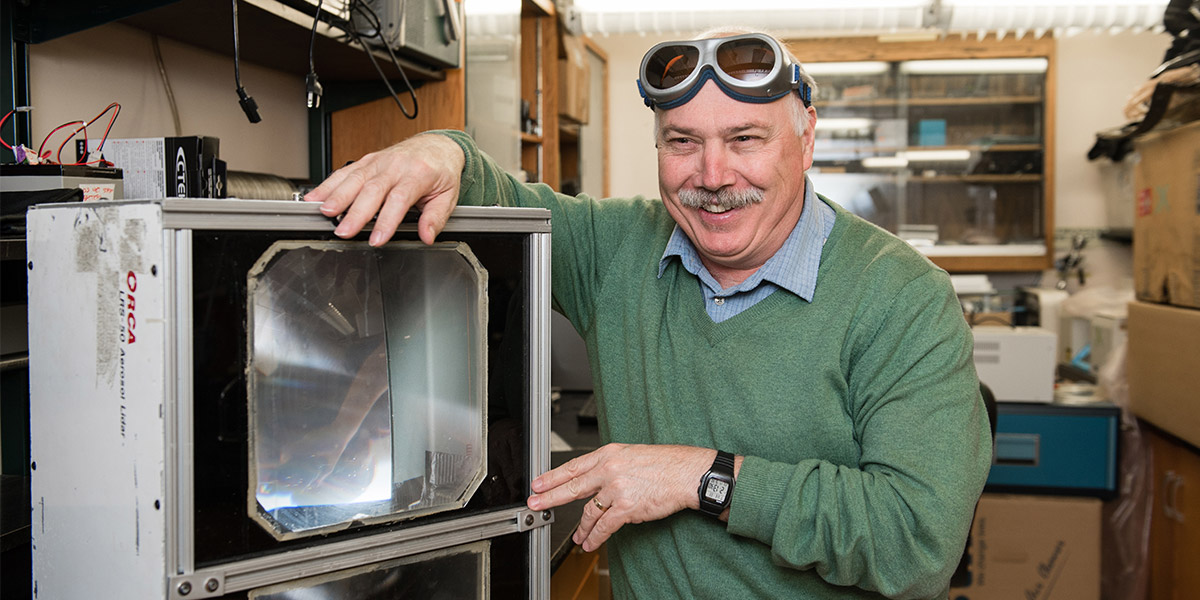

Michael Yost with an Orca LRS-50 Aerosol LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) he customized to better measure aerosol density over a section of sky.

These ideas have been around since the 1990s, but the existing lab instruments were big and clunky and usually required us to bring the sample into the machine. The idea of a smaller, field-deployable unit that measured gases directly in the environment was different.

Much of what we worked on was making the device calculate the concentration of a substance, say methane, and localize or map that distribution in space. It was a pretty big deal when we finally achieved it. It allowed people to apply this at places like Hanford, or in landfills. It has been used in many settings.

Highlights

- Winner, 2017 Rachel Carson Award, American Industrial Hygiene Assn.

- Outstanding Graduate Mentor (DEOHS) 2010, 2013

- Director, DEOHS Exposure Science Program, 1997-2012

- BS, MS, PhD, University of California (Berkeley)

Are you a hands-on tinkerer?

Yes, I do like to get down in the weeds. Soon after the OP-FTIR, we also wanted to measure fluxes and the emissions over time. Often it is hard to know the emission rate of something from a source over time. We were able to develop a method the EPA later adopted. The technique also was picked up by the US Department of Agriculture for measuring emissions from farms or ponds of decomposing material.

How did you get started as a scientist?

I got there because of prodding along the way and people who took an interest in me and my career. I was always interested in environmental sciences and was lucky to get a job as an undergraduate in a laboratory with Albert Krueger, who was a microbiologist and Naval officer. He did a lot of work on microbes and transmission of diseases in World War II.

When I was ready to graduate, he helped me get a job on a Navy project, which was fairly long-term. During that time I decided to get an advanced degree, and that was a pivotal moment.

I had many good experiences at Berkeley. You could stretch your imagination there. I worked in environmental health – but I was interested in electromagnetics. The Navy project I worked on included testing antennas. I was always interested in electrical engineering, so that was a great fit for me.

What got you started in a research career?

When I got my PhD, another mentor told me about a project with Steve Levine, a professor at Michigan, and that was a seminal moment. That project involved optical sensing of workplace contaminants, which again was a nice fit with my interest in electromagnetics. We got a NIOSH grant – that was something I didn’t anticipate. It took 10 to 15 years of work and we invented a bunch of stuff.

Yost, in rear, playing bass.

What’s drawn you to being a leader of the department at this time?

I could have kept just doing my research for another 10 or 15 years. But I’m interested in people. Organizations, like machines, require tinkering. How can I make it work well, and be resilient? I thought that was an interesting challenge.

I really like this place and want us to contribute and make a lasting impact. One more award for me or one more toy is fine, but self-serving. But if I could make this workplace better and have people feel better about their contributions to the world – that seemed like a good place to put my efforts.

What are some of your goals for the department?

Our strength is bringing in a lot of different disciplines to work on a problem. Getting people to work together is sometimes a challenge, but that is where all the interesting science happens. I want to build our interdisciplinary culture and foster that “eureka moment” of insight.

When I consider giving a short, elevator talk, I always say,

“We find ways to promote clean air, clean water, safe workplaces, safe food and healthy communities.”

If we can do all those things, it makes life better. What we do falls into those big buckets. I would like to see us partner with some businesses to help them improve the sustainability of what they are doing.

What’s next on the horizon?

We are looking at putting a focus on the human microbiome as a theme for our cross-cutting research next year. It is fascinating in many ways. It allows us to wonder – how does the environment interface with us? We can bring toxicology and microbiology into the investigation. We are poised to launch an initiative to seed ideas internally but also bring in outside experts. Knit things together as an area of focus.

With his youngest daughter Brenna, who recently graduated from WSU with a degree in communications.

One of your colleagues called you a Renaissance man. What are some of your hobbies?

I play guitar and bass. I’ve also picked up the ukulele.

Tell us a little about your family.

I have a wife and two daughters. One daughter just graduated from Washington State University. The other went to the University of Hawaii. My wife was an elementary school teacher – but is now working as a substitute.

(By Ashlie Chandler)

Originally published: May 2017