If it weren’t for a teacher who pushed her to pursue science, Rhea Coler could have slipped through the cracks as a young girl in Trinidad. Three degrees and five patents later, Coler is shaping the future of vaccine development and mentoring emerging leaders in global health.

Nestled in a quiet corner east of Seattle’s Lake Union, Coler and a team of scientists at the Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI) are doing painstaking work to save lives, reduce disease and improve health around the world. They have spent the better part of 10 years designing a tuberculosis (TB) vaccine capable of both preventing and treating the disease, whose pathogen has refined its survival strategy over at least 6,000 years.

Rhea Coler and her laboratory team at the Infectious Disease Research Institute.

Using state-of-the-art technology, Coler’s team screened the genome to find components that, when combined in the right amounts, produce an effective vaccine capable of preventing active TB disease, thereby decreasing transmission. IDRI now has the world’s largest collection of TB antigens, molecules that stimulate the immune system to attack TB pathogens, and scientists have found the right ingredient – or adjuvant – to boost the immune response.

“Producing vaccines is a lot like cooking,” says Coler, senior vice president of preclinical and translational research at IDRI. “You prepare all the ingredients and combine them with spices in certain amounts to create the flavor you’re looking for.”

Coler tested different novel adjuvants, also developed at IDRI, with specific antigens to see what worked to get the desired response. The combinations were then tested in cell cultures and in animals such as mice, rabbits, guinea pigs and monkeys. The promising vaccine just completed clinical trials in South Africa to ensure it is safe and retains the ability to generate an immune response.

Coler never thought it would be easy to beat one of the world’s greatest killers. TB remains a major global health problem that causes almost two million deaths annually. There is a vaccine used to prevent TB (called BCG), but it’s only partially effective, particularly in children. And while TB can be treated with long, complex courses of antibiotics, control efforts face difficulties with timely diagnosis, emerging drug resistance and reaching vulnerable populations.

“Developing a new, effective TB vaccine would be amazing,” says Coler, recognizing that scientific research needs to focus on "game changers," such as improved vaccines to achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal of ending the TB epidemic by 2030. “But it’s also important to me that I’m part of the process of developing the next generation of scientists.”

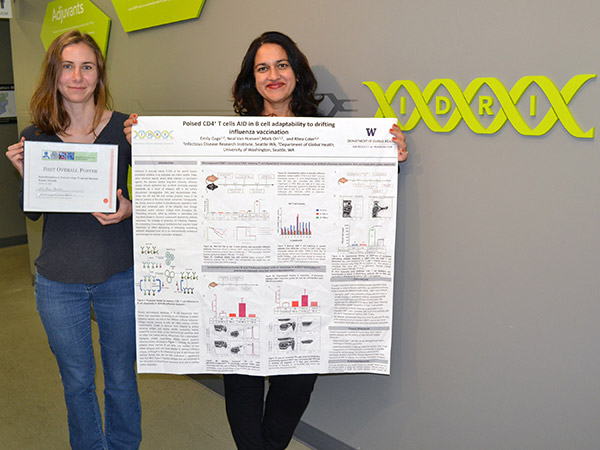

Coler with mentee Emily Gage, a PhD candidate in pathobiology at the UW.

Coler shares her expertise with students at the University of Washington School of Public Health as an affiliate professor of global health. She is currently teaching an undergraduate course on the biology of global infectious diseases.

A '98 doctoral graduate of the UW’s former Department of Pathobiology, now an interdisciplinary program housed in the Department of Global Health (which bridges the schools of Public Health and of Medicine), Coler has maintained strong connections to the program and mentored several of its students. Under Coler’s guidance, PhD candidate Emily Gage is studying the concept of antigenic sin. That is, how previous infections influence the ways in which the immune system responds to subsequent infections. Results from Gage’s work will have major implications on how vaccines should be designed.

In another project, Coler and Gage are studying ways in which adjuvants can be used in the very young as neonatal vaccines, as well as in the elderly to augment immune responses. Gage is also supporting Coler’s work to understand why some vaccines with adjuvants protect against viruses, such as West Nile and Zika, and others do not.

Coler has trained four other pre-doctoral researchers and 10 post-doctoral researchers over the years. Some have gone on to work at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership and the National Institutes of Health.

Coler doing field work in Tanzania.

Coler was originally drawn to the pathobiology program’s strong integration of laboratory research and global health. The program applies a multidisciplinary approach and the latest research technologies to the study of viral, bacterial and parasitic disease, as well as infectious contributors to chronic diseases such as cancer.

More than 100 PhD and 40 master’s students have graduated from the program, directed by Lee Ann Campbell, professor of global health. Graduates are working at academic and non-governmental research institutes, in biotech and health-related government positions, or are in business or clinical medicine. Twenty-seven students are currently pursuing their PhDs in the program.

“It has always been important to me to have strong connections with people,” Coler says. “I’ve had many fabulous mentors and now I strive to be a good mentor for others.”

Coler with her son, Brahm, 20; daughter, Celeste, 16; and husband, Clark, in Thailand.

Coler grew up at a time when boys were encouraged to pursue science and girls were politely pushed in other directions. Her earliest mentor, a high school chemistry teacher, recognized her potential and encouraged Coler to pursue a STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) degree in college. At McGill University in Montreal, she studied physiology, a branch of biology that deals with the function of living organisms and their parts. Her passion for parasites, however, would lead her in a different direction.

“When I was five, I had dolls and I had my spiders,” says Coler, who collected a colony of the critters under her house in northwest Trinidad, the larger and more popular of the two islands of Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean. “I was always curious about science, natural history and bugs.”

After college, she landed a research position with the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, where she worked closely with parasitologists to breed mosquitoes and test resistance to insecticides. She also volunteered to be bitten as part of the research. That same year, howler monkeys on the island were dying at alarming rates and forest-workers were falling ill. Coler helped to investigate and collect monkey carcasses for testing. They later learned the monkey deaths were a warning sign for a yellow fever outbreak.

Coler and her family on a recent trip to Southeast Asia.

“That work fueled my interest in global health,” says Coler, who eventually enrolled as a master’s student in medical parasitology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “The process of discovery was very exciting. I was hooked.”

She first got involved in antigen discovery as a member of Geoff Targett’s lab, aiding in the search for new strategies that could lead to an effective malaria vaccine. She was also a protégé of Chris Curtis, a medical entomologist who showed the value of insecticide-treated bed nets for preventing malaria and “was an advocate for straightforward, low-tech methods of disease control.”

Years later, while pursuing her PhD, Coler connected with Steve Reed, IDRI’s founder and chief executive officer (and affiliate professor of global health). The two clicked and Coler was invited to join Reed’s quest to develop products to solve critical global health challenges. Among her greatest achievements is IDRI’s candidate TB vaccine, which targets the different stages of the disease (i.e., active and latent), provides long-lived memory immunity and has also shown to be effective against drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains of the pathogen in animal studies.

Coler was also integral in building IDRI’s virology group, which recently received funding to take a West Nile vaccine from the pre-clinical phase to toxicology testing. She is optimistic that their approach to West Nile could also work for Zika. Finally, she is a key player in transferring IDRI’s technology to other countries – making vaccines available to people who need it most.

Coler (kneeling; far right) with the Lake Washington Rowing Team.

Her commitment to cultivating relationships extends beyond the lab. Her home in Magnolia is “the gathering house” for family, friends and neighbors. She enjoys spending time with her husband, Clark, a physician; her son, Brahm, who’s studying at Whitman College; and her daughter, Celeste, a junior at Lakeside High School. She takes part in a book club and works out on the water with the Lake Washington Rowing Club. She also enjoys cooking and recently spent a late night making tiramisu for Emily Gage’s birthday.

“Real success is impossible without building great relationships,” Coler says. “Strong, positive relationships are also a secret to innovation, productivity and happiness.”

(By Ashlie Chandler)

Originally published: 2018