Countless lives were saved through Mary Selecky's public health efforts. During her 14 years as Washington State Secretary of Health, adult smoking rates dropped nearly a third. More children are vaccinated against disease, while the state is better prepared for earthquakes, floods and epidemics. Selecky also promoted patient safety and better partnerships with Canada. "Bugs know no borders," she says. Before retiring in April, she helped Washington become one of the first two state health agencies to receive national accreditation.

What was your biggest accomplishment?

Mary Selecky recalls highlights of her 14 years as State Secretary of Health

Tobacco would be at the top of the list. We came up with a tobacco prevention and control plan in 1999 and went from being 20th in the nation for adult rates to seventh. Smoking rates were at 22 percent. Now we're at 15 percent. It's still way too many. When you look at the populations, the smokers are Native Americans, they're in rural areas, they have lower education, lower income, and they don't get much support for quitting. African-American men still smoke too much. The tobacco companies still spend $144 million in our state trying to get you to pick up the habit or to switch brands or to try new flavored cigarettes.

Now that marijuana is legal in our state, what are the health impacts of smoking it?

Smoke is smoke and it's still in your lungs. Cleary, we don't have much research. That's something that public health might want to look at.

How were you able to turn the tide on childhood immunization rates?

Our challenge was the media gave great voice to concerns that vaccines caused autism. It wasn't based on any science. We, and I mean the whole public health system, weren't prepared for the kind of questioning that went on. We had to work very hard on how to have those kinds of conversations with parents. Our vaccination rates actually have gotten better. At one point we were 46th in the nation. How embarrassing! That's not a number a Secretary of Health wants. We were the state with the easiest way to opt out. We are now about number 16 in the nation in terms of children under 3 having received the vaccinations they should.

Why was emergency preparedness so important to you?

In February 2001, we had an earthquake in this state. We were not prepared. September 11th was a defining moment and so was the anthrax scare. The public said, "Where's our public health system? Oh my. We have not invested in it." The state upgraded our laboratory capacities in Shoreline, increased our epidemiology capacity and worked to have public health workers understand the whole world of emergency preparedness. We relearned how to set up mass immunization clinics. We've got to look at a whole community if something bad happens.

You served under three governors, making you one of the longest-serving Cabinet members.

I was the last man standing, as it were, from the (Gary) Locke Cabinet.

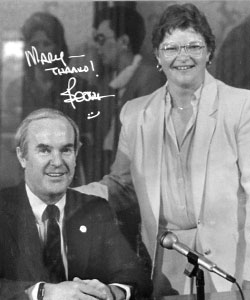

Governor Booth Gardner and Mary Selecky after creation of the State Health Department in 1989.

What was the secret to your survival?

Understand your authorizing environment. You really need to have your antenna up all the time. You need to pay attention to the governor's priorities, and how to help shape them around the issues of public health. Very few officials get elected saying, "I'm for public health." That is not a very rallying cry. But public officials find themselves in trouble if their public health system can't respond in a way the public expects, whether it's an epidemic or a natural disaster or an event such as Fukushima.

Why did you move to Washington?

The beauty of the West. I graduated from college in 1969 and it was the early '70s. There was a wanderlust. I still own the 30-plus acres and my home in Colville. In May, I'll have been a Washington state resident for 39 years.

How did you get into public health?

My first job was in economic development – for a three-county region in northeast Washington. Then the Northeast Tri-County Health District was formed. The county commissioners were looking for an administrator and I said, "Gee, do you think I can do that job?" The rest became history.

HIGHLIGHTS

- BA, History, Political Science, University of Pennsylvania

- Former Administrator, Northeast Tri-County Health District

- Dean's Council, SPH

Tell us about a defining moment.

There was a day when a public health nurse stood in the doorway with her hands on her hips, and said, "You're nothing but a young whippersnapper. You don't know anything about public health." I said, "Well, I better learn." It's not just about writing the grants and doing the administrative stuff. It's about being the head of an organization that's doing some pretty darn important work. So I'd go out to clinics and I'd look at septic tanks and I'd go out and inspect a restaurant. When I came to the state, I went out on a boat with our shellfish staff. I followed people to see what they do.

What public health skills do our graduates need to succeed?

You've got to be curious. Seek out information from all kinds of places. What does the public think about this? What do I know about this? What is it I have to tackle? What has worked somewhere else? Every discipline has a role in what we do in public health. Whether you're a communications person or an epidemiologist or a researcher or public health nurse who goes on a home visit, or an environmental health person who answers a question about radiation.

You've got to have communication skills. Risk communication has got to be one of those very basic things everybody has to learn. You have to be able to help people understand what they have to do to save themselves. Because much of our health status is based on behavior.

"PUBLIC HEALTH AND POLITICS DO MIX. THEY AREN'T TWO WORLDS."

You have to know your stuff. The thing about public health is that many of us go to work in governmental systems. Public health and politics do mix. They aren't two worlds. If you're going to influence by policy, you have to know the differences between your public health science and knowledge, and the politics (the authorizing environment, whether it's a city, county or state or federal entity) to help create the policy that you want implemented.

What's next for you?

I need to get grounded in community again in eastern Washington. That's my long-term home. I am on some national boards and that will continue. Rural health issues are important to me and I will find my path on that.

What advice did you give the new secretary, John Wiesman?

This is a public health system. Protect it. Understand and respect your role in emergencies. You'll be glad you did. Practice risk communication. You'll need it. Buddy up with other state agencies. Public health can't do it alone. Get active nationally, because your problems aren't unique.

(By Jeff Hodson)

Originally published: 2013