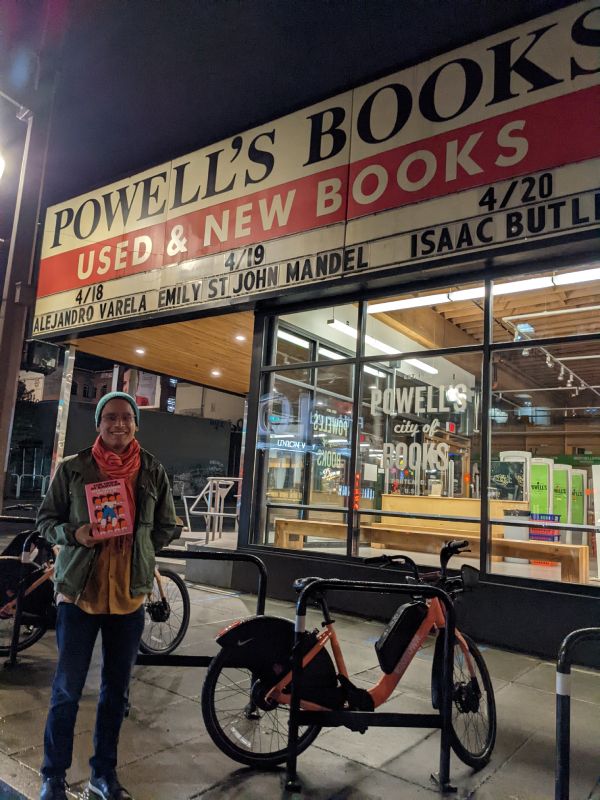

Alejandro Varela (Photo: Allison Michael Orenstein)

Even as a kid, Alejandro Varela has been able to take a complicated topic and turn it into language that makes sense for everyone in the room.

As a child of immigrant parents from El Salvador and Colombia, Varela acted as family spokesperson and interpreter for the Spanish speakers in his family. This required understanding complex subjects, translating nuance, and developing a sense for when someone was confused.

Varela has continued his work as an interpreter of language and ideas, but this time, for public health. A 2006 Master of Public Health alum of the University of Washington (UW) School of Public Health (SPH), Varela is an author and 2022 National Book Award finalist. His novels and stories take public health topics — from systemic racism to gentrification to sexuality — and make them accessible and memorable.

“I’ve always tried to communicate and write in a way that can reach as many people as possible, and I’m attuned to the miscommunication happening around me,” Varela said. “When I want to advocate for something or talk about a research finding, I will struggle to get it down to one good sentence because I want somebody to think, ‘Woah, I hadn't thought about it that way.’”

Varela was awarded SPH’s 2023 Alumni Impact Award, the highest honor the School gives to alumni for distinguished service and achievement across public health. His ability to use fictional stories and art as a means of accessible public health dialogue reveals lessons for public health schools and professionals alike.

“Alejandro has found an innovative and effective way to talk about important determinants of health, reaching a broad audience through the art form of fiction,” said SPH Professor Amy Hagopian. “This is creative public health work, smuggling public health concepts into places where people don’t expect to see them. He’s practically a public health worker in disguise!"

Many jobs, one public health career

Varela grew up in Long Island, New York, but moved to Seattle in the early 2000s as his partner was starting a job at a then-nascent Amazon. Varela hadn’t planned on becoming an author or a public health worker, but was interested in social justice and community organizing. He was considering a master’s in international relations until he learned about the Community-Oriented Public Health Practice program at the UW School of Public Health.

“I got a degree in public health and my life’s been changed ever since,” Varela said. A student in the Department of Health Systems and Population Health, he was inspired by professors and mentors Amy Hagopian, Stephen Bezruchka and Sharyne Shiu-Thornton, who he said helped him consider societal problems in a collective way.

Soon after he graduated, his partner got a job on the East Coast, so they moved back to New York City. He worked on an HIV study for the New York City Blood Center, managed cancer screening studies at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, began a self-led documentary on the effects of racism on health in New York City, and consulted with the UW’s International Training and Education Center for Health to write health curriculum for Ministries of Health in places where HIV was at epidemic levels.

He went on to teach graduate-level public health policy and advocacy at Brooklyn's Long Island University. He brought in activists to speak on trans health rights, bike lanes, HIV/AIDS decriminalization and treatment access, and grassroots health policy creation. He assigned his students to write public health op-eds, several of which were published in newspapers. Varela began writing op-eds too, and while at first he felt inspired by sharing public health messaging with a broad audience, he also realized that the market for opinion pieces was oversaturated.

He instead mulled over mediums of storytelling that resonated with him over the years, like literature, songs, television, theater and films. He was inspired to create a narrative film that incorporated public health messaging. But when he sat down to write what he thought would become a screenplay, he ended up with his very first short story.

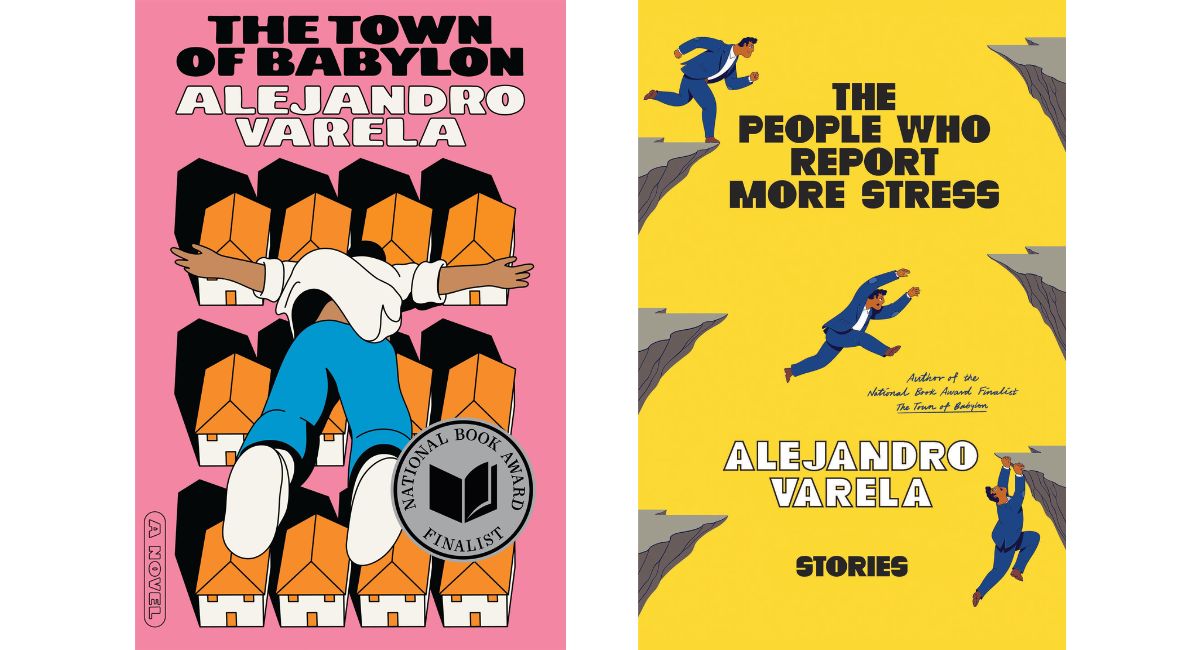

That was the start of his journey as a fiction author. Since then, he has published dozens of short stories, which have appeared in The Point Magazine, Georgia Review, Boston Review, Harper's, The New Republic and The Offing, among other outlets. His debut novel, “The Town of Babylon”, was published in 2022, and is about a public health professor who returns home to take care of his ailing father. This book was a nominee for the PEN America Open Book Award and the Aspen Literary Prize, as well as a finalist for the National Book Award. Through it all, Varela has stuck with his goal of sharing public health themes through stories.

Sharing public health through art

There are many ways to deliver public health messaging. Some people respond to blunt, fact-based messaging: People who smoke are more likely to develop heart disease, stroke and lung cancer. Some people respond to fear-based messaging: This is a picture of what your lungs will look like if you don’t quit smoking. Some people need an emotional connection: This is how your life could change if you quit smoking. The important thing, Varela said, is that the messaging is personalized to the listener.

Varela learned this first-hand when he was trying to quit smoking in graduate school. Varela had been smoking since he was 13, but his attempts to quit over the years hadn’t worked. At the time, Washington state had a tobacco cessation hotline. Through that, Varela had a few sessions with a counselor who created a personalized plan to help him quit smoking.

“They said to me, ‘It’s obvious you care what people think about you, so pick a day when you want to quit smoking, tell everyone you know that you are going to quit on that day, have a party, and that’s the last day you're going to smoke.’ I did that and it has been 18 years. I haven't had a cigarette since,” Varela said. “I am just vain enough that I would have been embarrassed if someone had seen me smoke because they would have said, ‘You made such an effort!’”

Varela personalizes public health messaging through his storytelling. When he sits down to write a fictional story with real-world public health themes, he thinks of these different communication methods. He thinks of the lawyer-type, who may have 10 rebuttals waiting for him, so he includes defenses of those arguments in his story. He thinks of people like his family, who don’t want to be coddled but want to be told something directly. He thinks of people who have never thought of the topic before, and how to make the idea seem like common sense.

He also knows the power of a well-crafted sentence across art forms, from films, to books, to songs. Public health workers don’t need to write fiction to take lessons from Varela’s writing. He challenges public health professionals to distill their work, their research, or an issue they’re passionate about into forms of communication that are accessible to as many people as possible.

“There are those memorable lines that everyone has in their minds, and I never take for granted that a really well-crafted moment of dialogue or one powerful paragraph can stick with people for a long time. People get those things tattooed on their body!” Varela said. “With larger policy questions like Land Back for Indigenous nations of this country, reparations, and a national health service, sometimes I think what's missing is a really common sense statement that people can't refute.”

How everyone can take an upstream approach to public health

When Varela teaches graduate students, he shares the importance of umbrella or upstream policies — ones that address root causes of problems rather than symptoms. These policies can have a big impact on many, seemingly disparate public health issues, from diabetes to lung cancer to heart disease.

“What if we found that the one thing these 10 or 20 illnesses had in common was elevated levels of cortisol caused by stress from day to day living?” Varela said. “Then wouldn't it make sense that we would try and reduce the elements of society that lead to chronic cortisol?”

“I'm not talking about the stress you might have from a job interview or public speaking or the birth of your first child,” Varela continued. “I'm talking about the day to day, ‘Am I safe? Am I being judged? Do I have dignity in this life? Will I be able to pay the bills? Are my kids healthy?” Varela said. “That stress stays with you all day long.”

The ways racism, class conflict, and income inequality impact people’s stress is the subject of Varela’s newest book published in April of 2023, “The People Who Report More Stress.” The short stories chronicle the stress characters face from living in an unequal society, including those who have climbed the socioeconomic ladder and are well aware of how difficult life is for many of their family and peers.

The stories also chronicle the need for a collective approach to addressing our public health issues. In the short story, The Great Potato Famine, a character is frustrated with the short-sightedness of an op-ed writer who fumes that people don’t care about climate change’s imminent impact on the planet: “Misplaced anger in my opinion,” the character muses. “People won’t confront anything they perceive as far away or out of their control, like heart disease or the world’s end, if they can’t first meet their own needs, like rent or diapers.”

While public health professionals work across the spectrum of upstream to downstream work, Varela challenges every professional to consider how they can devote at least 10% of their jobs to addressing the issues at the root of health inequities. He says this is also a pivotal role for schools of public health to take, to train their workforce on how to devote time to making everyone’s lives better in the long run.

Varela will address the Class of 2023 at the University of Washington School of Public Health’s Graduation Celebration on June 11, 2023.

“Historically, commencement speakers tell graduates they shouldn't lose sight of who they are and to be true to themselves, and I beg to differ,” Varela said. “I would like to encourage public health students to evolve and to be true to the best version of themselves they can imagine. It’s ok if we’re not the same people as we age. We should change with the times, and that involves introspection.”