Photo credit: University of Washington

It doesn’t matter if someone has health insurance if they don’t have a mode of transportation to get to a doctor’s appointment.

That’s one of the many lessons students at the University of Washington School of Public Health learned this past year from rural communities locally and globally, in an effort to understand and improve health disparities.

These students were engaging with rural communities through their practicums, a field-based experience with a public health organization required for their master’s in public health (MPH) degree. They learned that rural communities face challenges that are often compounded by intersecting inequities. These challenges include inadequate access to broadband, transportation, as well as shortages of funding and staffing at health care facilities.

Communities in rural areas face many health disparities compared to those living in urban areas, and are more likely to die from heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, chronic lower respiratory disease and stroke, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Globally, 63% of the world's rural population do not access health care because of underfunded global health financing, compared with 33% of the urban population, according to The Lancet.

But communities in rural areas have also been innovative in seeking solutions to solving these health care challenges, by collaborating with each other to share resources and reimagine how existing services in their community could be repurposed. Most importantly, rural communities are not a monolith, and while ideas can be shared, creating healthy communities globally means listening to the unique needs of each one.

“So much of public health is setting communities and populations up for success and having systems in place that allow people to live healthy lives,” said Elena Soyer, a Health Systems and Population Health MPH student.

Transportation in rural Washington

Having reliable transportation is critical to seeking care at a hospital, but in rural areas with low ridership, public transit is rarely an option. That’s why health care facilities in rural areas across Washington state have been brainstorming how to get their patients to non-emergency appointments.

Elena Soyer has been learning from those health care facilities. Having lived in cities with robust public transportation systems from Boston to Valparaíso, Chile, Soyer wanted to learn how access to transportation impacted rural communities. As part of her practicum project with the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) and the Washington State Health Care Authority, she conducted interviews with people working in health systems, hospitals and transportation for the state and in rural areas to learn about needs and opportunities for improving transportation.

Soyer also read through literature to research other barriers to transportation. She then created a resource library for these agencies to use for writing grant applications, finding case studies and disseminating information to get more resources to rural areas.

One solution that some hospitals have begun to adopt is purchasing their own car to pick up and drop off patients. They have also been brainstorming ways to leverage Emergency Medical Services (EMS) for non-emergency purposes as a mode of transportation. This could be coupled with leveraging the knowledge of EMS responders and firefighters, who usually know the people who are most frequently calling 911 and can pre-plan rides.

"Being able to get from point A to point B is such an important piece of getting to live your best and healthy life."

As is often the case with health disparities, transportation is just one issue that intersects with others, such as lack of access to reliable broadband or mobile devices, which can compound the problem. Additionally, Washington state is geographically diverse, meaning that communities living in the mountains will have different challenges from those living in the desert or rolling farmlands.

That’s why it’s important for leaders to address public health needs that are specific to rural areas, said Claire Horton, primary care office program manager at DOH and Soyer’s site supervisor.

“Implementing programs designed for urban communities doesn’t necessarily translate to rural,” Horton said. “We need to do better at supporting ‘home grown’ rural public health.”

Communication connections in Zimbabwe

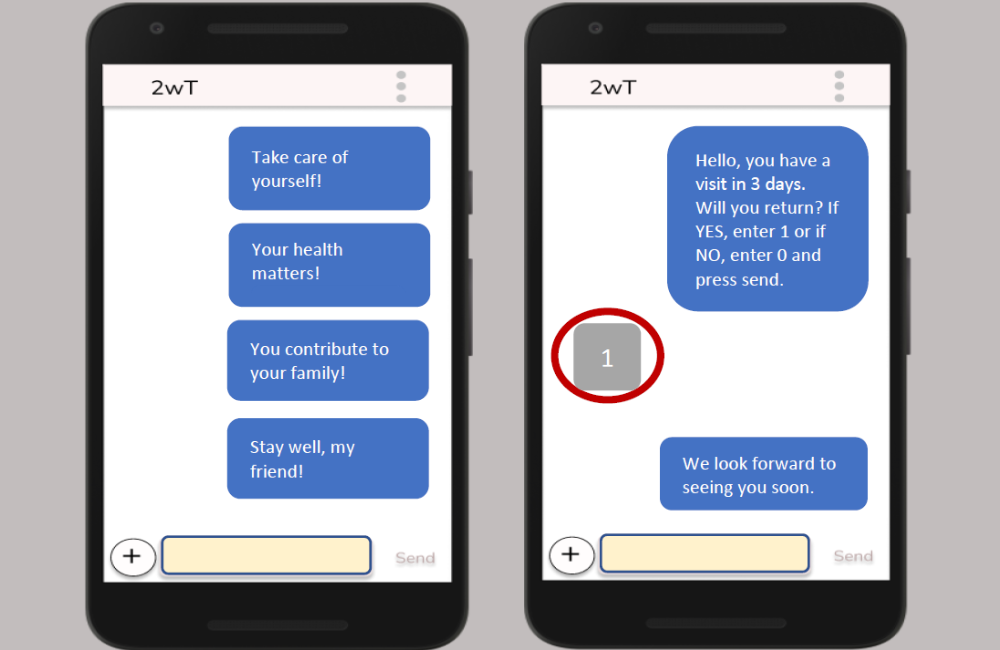

Some patients in rural Zimbabwe receive a follow up visit after a major procedure in the form of a ping on their cell phone. A two-way texting program has been helping increase access to health care for these rural communities, while decreasing demand on short-staffed health care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sulemana Abdul-Matinue, a Global Health MPH student at the UW, helped study this two-way mobile communication system for his practicum. He worked on the Zimbabwe team of the International Training and Education Center for Health (I-TECH). I-TECH is a center in the UW Department of Global Health that strengthens long-term capacity in health systems; human resources for health; and targeted, data-driven interventions and research that are responsive to local needs.

The two-way texting program specifically focused on the post-operative care of men who had received routine voluntary medical male circumcision. The day after returning home from their operation, the patient will receive a text that asks them how they’re doing. The patient can respond with questions and receive treatment advice from a health care worker, or a recommendation for further in-person care.

Abdul-Matinue studied transcripts of interviews conducted with health care workers to understand how the program was going.

One of the challenges was access to broadband and phones. In rural communities, broadband connections are very slow, or sometimes nonexistent, which can make it difficult to have conversations with patients.

“Most of the time, connectivity is low in the rural areas where I was working as a nurse in Ghana, so I know that for the Zimbabwe project, rural connectivity is always bad and you can't do anything about it because of the telecommunication giants,” Abdul-Matinue said. “So you have to look at ways you can still reach out to clients.”

Patients sometimes live in households where a family shares one phone, which can make it difficult if multiple people in the family are trying to access the two-way texting service for health care advice. Attrition of health care workers was another challenge: when health care workers who were trained on the texting program would leave, new workers would need to be trained on how to use the software.

Abdul-Matinue was able to present recommendations for the program based on his findings, such as expanded training of health care workers and the ability to enroll multiple people per phone in the texting service.

Growing up in a rural area in Ghana, Abdul-Matinue understood the challenges rural communities face when it comes to accessing health care. Before coming to the UW, he worked as a public health nursing officer with the Ministry of Health for years in rural communities in Ghana, providing immunization services, nutrition counseling, reproductive/adolescent health care and family planning services. He had a passion for improving health in low-resourced populations, including maternal and child health as well as public health policy research, and so he pursued his master’s in public health in the hopes to further help communities like the one he grew up in.

“I'm working to help people who were just like me: people in rural communities,” Abdul-Matinue said.

Infections in hospital

On any given day in the U.S., about 1 in 31 hospital patients will experience a health care-associated infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These infections can come about from inserting catheters or from a wound after surgery, and can cause serious illness or death.

Tracking and preventing these types of infections is critical for health care facilities, including the Washington State Department of Health. As part of her practicum, Liz Mariluz, a Health Systems and Population Health MPH student, helped the DOH study how the agency can better assist rural health care facilities with reporting and preventing health care-associated infections.

While Mariluz wasn’t studying epidemiology, she was specifically drawn to the role for its focus on taking a health equity lens in this work. Mariluz has long been interested in health equity, especially growing up in a Latino family and seeing firsthand the systemic challenges they faced navigating the health care system.

Every week for the practicum, Mariluz would meet with the health equity workgroup at the DOH, which was a team of infectious disease experts, epidemiologists and project managers, to share what they’d found from their own research on challenges rural health care facilities were facing.

They learned that a lack of trained staff in rural facilities is one of the biggest barriers to tracking, reporting and preventing these infections. That’s why many health care workers in rural facilities have been collaborating with their colleagues in other remote areas to share knowledge and best practices.

“That’s what I found in my research, that when it comes to rural health care facilities, collaboration is such a needed thing,” Mariluz said. “It doesn't seem like it because so many facilities are far away from each other, but they are collaborating with each other because they have such similar challenges on reporting infections.”

It’s also important for departments of health to collaborate with rural health facilities, Mariluz said. In one conversation with an infection preventionist in Port Townsend, Washington, Mariluz learned that the facility found it helpful when the Department of Health paid for a consultant to work with the facility and review their practices and recommend improvements.

Funding for technology is also a big barrier. One facility said the most helpful thing that could be done was paying for a new electronic system to track infections, as their team still had to do things manually. But the cost of funding such a system was out of reach for that facility.

Based on her research, Mariluz helped create a survey that would be disseminated toward rural health care facilities. Her research will also be part of the basis of focus groups of rural health care facilities that the DOH team can work with and learn from in the future. Ultimately, this can not only help save lives from health care-associated infections, but also improve systemic issues faced by many trying to access equitable health care, regardless of where they live.

"I really want to understand the different ways we can address health inequities and overall make the health care system an easier space to work in and navigate as an individual."

MPH Practicum Symposium

Join us for the 25th annual MPH Practicum Symposium.

Virtual sessions April 17-20.