For several months, Priyasha Maharjan traveled with a translator to the homes of Seattle Afghan community members. She’d remove her shoes, greet the women who welcomed her into their homes, and then watch them cook dinner.

Maharjan ate with families, asked them about their recipes, and listened as they told stories about their search for traditional Afghan ingredients in the Pacific Northwest. She worked with fellow student Norma Garfias Avila and a translator to create a resource with their findings for local health providers in Seattle to help them understand the cultural dietary practices of their Afghan patients.

Understanding food accessibility, affordability, diet and cultural practices is important for supporting the health of communities. In Seattle and King County, food insecurity is increasing, as indicated by the number of people qualifying for federal food emergency assistance programs. In South King County and South Seattle, residents are twice as likely to experience food insecurity. Lack of access to affordable, healthy foods is one of the many contributing factors to heart disease, diabetes and obesity in the United States.

That’s why several master’s of public health (MPH) students at the University of Washington School of Public Health have been working with Seattle-based organizations through their practicums to address the nutritional needs of people in the community, especially refugees, people of color, and people living in South King County. Through this collaboration, they’ve been learning ways to improve access to healthy food.

“Food is a basic human right and I think everyone deserves to have access to food,” said Felicidad Smith, a recent graduate of the Health Systems and Population Health MPH program. “Something like that shouldn't be politicized or stigmatized.”

Bridging cultural nutrition knowledge between health providers and communities

Maharjan’s practicum with the Afghan community in Seattle was conducted with EthnoMed, a website run by Harborview Medical Center that contains medical and cultural information about underserved populations, including immigrant and refugee groups. The EthnoMed team has been creating resources for local health providers to help them support the unique health needs of these communities in King County, including those from Afghanistan. Maharjan, a Fulbright scholar from Nepal and recent Global Health MPH graduate (now a UW doctoral student of global health leadership and practice), felt this was a great fit for her expertise and learning goals. She and recent MPH student Norma Garfias Avila (now UW nutritional sciences doctoral candidate) are co-authors of the project.

“Especially in Seattle, diabetes and hypertension are growing in these communities, and when they seek care at Seattle-based hospitals, the providers are unaware of dynamics in a household,” Maharjan said. “So if the provider recommends an American diet to an Afghan family, it is less likely the family will adopt the recommendation and change their food behavior. But if the provider recommends a diet that is culturally appropriate, if the family can relate to the recommendations being made, they are more likely to accept those changes and adjust their lifestyle accordingly.”

To go about creating these culturally appropriate recommendations for health care providers, Maharjan worked with a translator to visit the homes of Afghan families and learn from them about their culinary practices. During these visits, Maharjan interviewed and observed how important it was to the women cooking the meals to make their food healthy for their families, and how integral it was to eat together as a family. Those with younger children were more influenced by American diets than families without children.

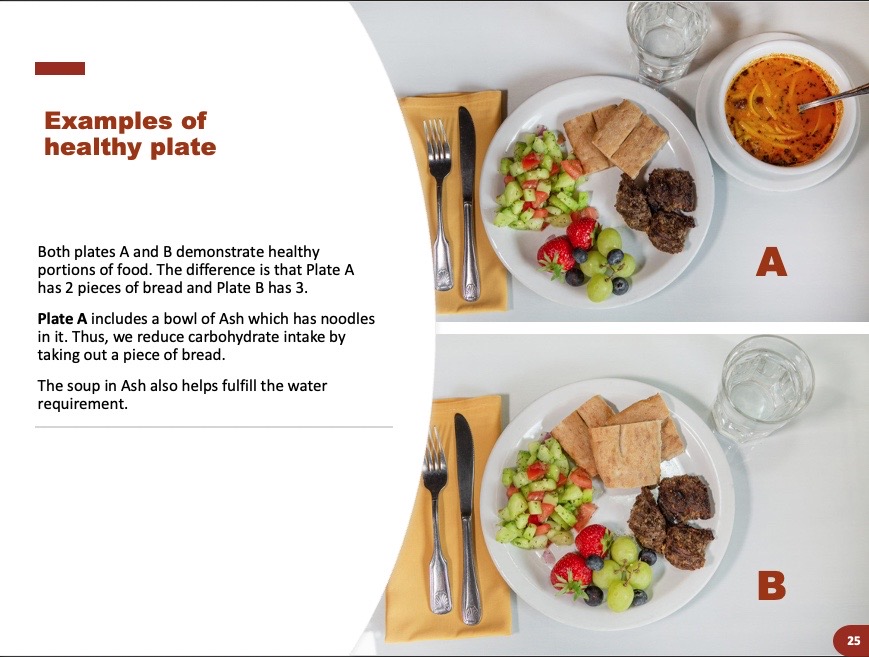

Maharjan and EthnoMed’s Web Information Specialist Nityia Przewlocki took pictures of the meals to include in a guide for health providers, so that they can understand typical foods served, portion sizes, and the balance of carbohydrates and proteins that their patients typically consume. Maharjan also made suggestions for local vegetables that could be added to meals like stews, such as leafy greens or carrots. The guide is under translation and will be available in English, Dari and Pashto languages.

The resource also provides culturally-appropriate guidance for health providers during times like Ramadan, where fasting of all food and drink occurs from dawn until sunset. It gives suggestions like drinking plenty of water to support hydration after breaking fast, especially before consuming sugary treats. It also suggests eating fibrous foods during evening meals to help support individuals’ energy during their month of fasting.

“I've learned more about how to communicate with communities about their practices,” Maharjan said of her 6-month experience with EthnoMed. “When trying to make changes or suggesting something, it’s important to practice cultural humility so people feel respected and heard and that we’re not pushing our ideas, but listening to them and trying to effect change that is driven by a community’s own interest.”

Increasing access to farmers markets

Many local farmers markets in Washington state offer a $1 for $1 match to people who receive food benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Called the SNAP Market Match, the program increases access to locally-grown fruits and vegetables.

Yet few people are actually using these benefits due to lack of knowledge that the program exists or lack of access to their local markets. For example, in Auburn, Washington, 17,661 people had access to this match program in 2019, yet only 188 households used it.

“That was a shocking number, to say the least,” said Felicidad Smith, a recent MPH graduate of the UW School of Public Health. “Increasing access to farmers markets is really important because when you’re looking at some of the top chronic diseases that a lot of people are dying from in this country, a lot can be related to nutrition.”

During her MPH practicum experience, Smith worked with the Healthy Eating Active Living team at Public Health – Seattle & King County (PHSKC) to understand the barriers communities faced to knowing about and accessing benefits at farmers markets. Smith helped design a survey for residents of South King County, especially aimed at those who are refugees or immigrants. Community representatives then attended seven markets in South King County to distribute the survey.

“We know SNAP users are still food insecure, so the SNAP Market Match program is a way for them to increase their food budget,” said Seth Schromen-Wawrin, a project manager at PHSKC. “However, it requires getting to a farmers market, feeling like a farmers market is a place you are able to go, and understanding how to use SNAP at a farmers market. All these knowledge, social, and physical barriers might prevent someone from being able to use this resource.”

From the survey, Smith learned that barriers to access included lack of awareness, limited hours of operation, the difficulty of taking children to the markets, and lack of information in peoples’ own languages that communicated these SNAP benefits. Yet she also discovered that farmers markets were one of the few gathering spaces for many communities that you could go to without necessarily having to spend money, especially people looking to form new communities after moving to the United States. Farmers markets aren’t only about food, as they can also include musical performances, dancing, street drawings and activities for children.

“There’s this common misconception that when you think of a farmers market, you think that everything is very expensive and overpriced and it’s mostly for white people to shop with their dogs,” Smith said. “But what we learned from the surveys is that it's actually a great place to foster community for people within their own demographic areas. Some people said that the primary driver for visiting farmers markets was to support farmers who looked like them.”

Public Health – Seattle & King County received a three-year grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to improve access to farmers markets through promotion, so the data from Smith’s research will help with this, Schromen-Wawrin said. This is especially important as farmers markets are often run by either a single person or a group of volunteers, so having PHSKC do the promotion and outreach helps small and time-strapped teams.

One of the ways PHSKC has been promoting the markets is by using a peer-to-peer outreach approach to assign trusted messengers within a community (such as community organizers or nonprofits leaders). Smith’s data also helped work as an evaluation of how well this peer-to-peer outreach has been doing. Smith and Schromen-Wawrin eventually presented their findings at the Washington State Public Health Association conference in 2023.

“I'm hoping that the biggest impact of this work is seeing more folks coming to the farmers market to use their SNAP benefits there,” Smith said. “While still acknowledging that fruits and vegetables can be very expensive, having more access can help tremendously with nutrition-related diseases.”