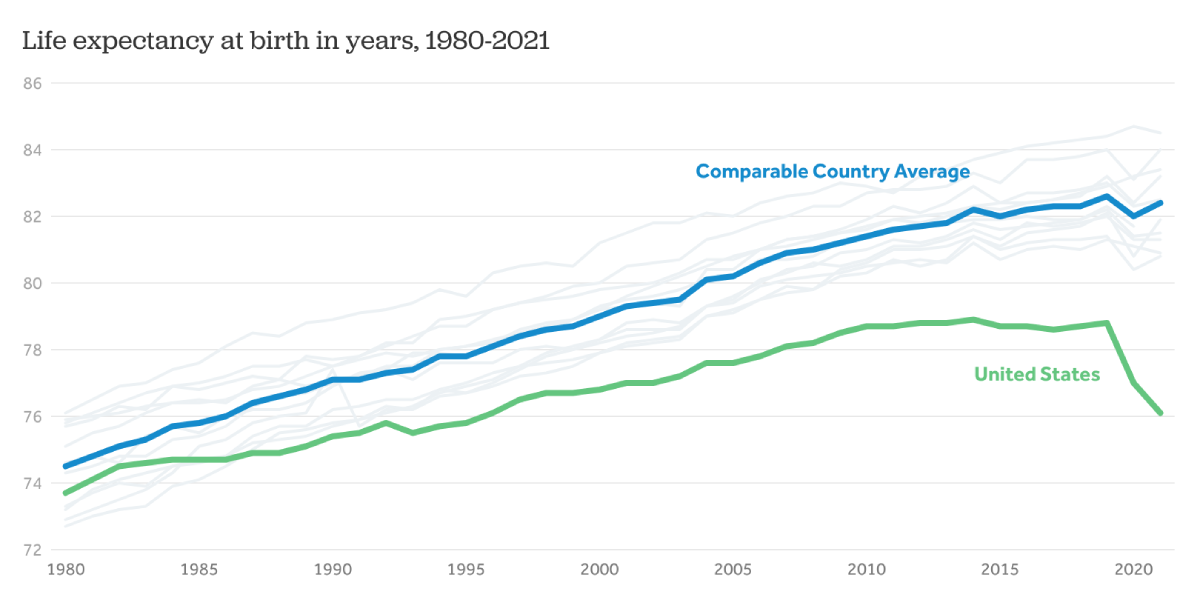

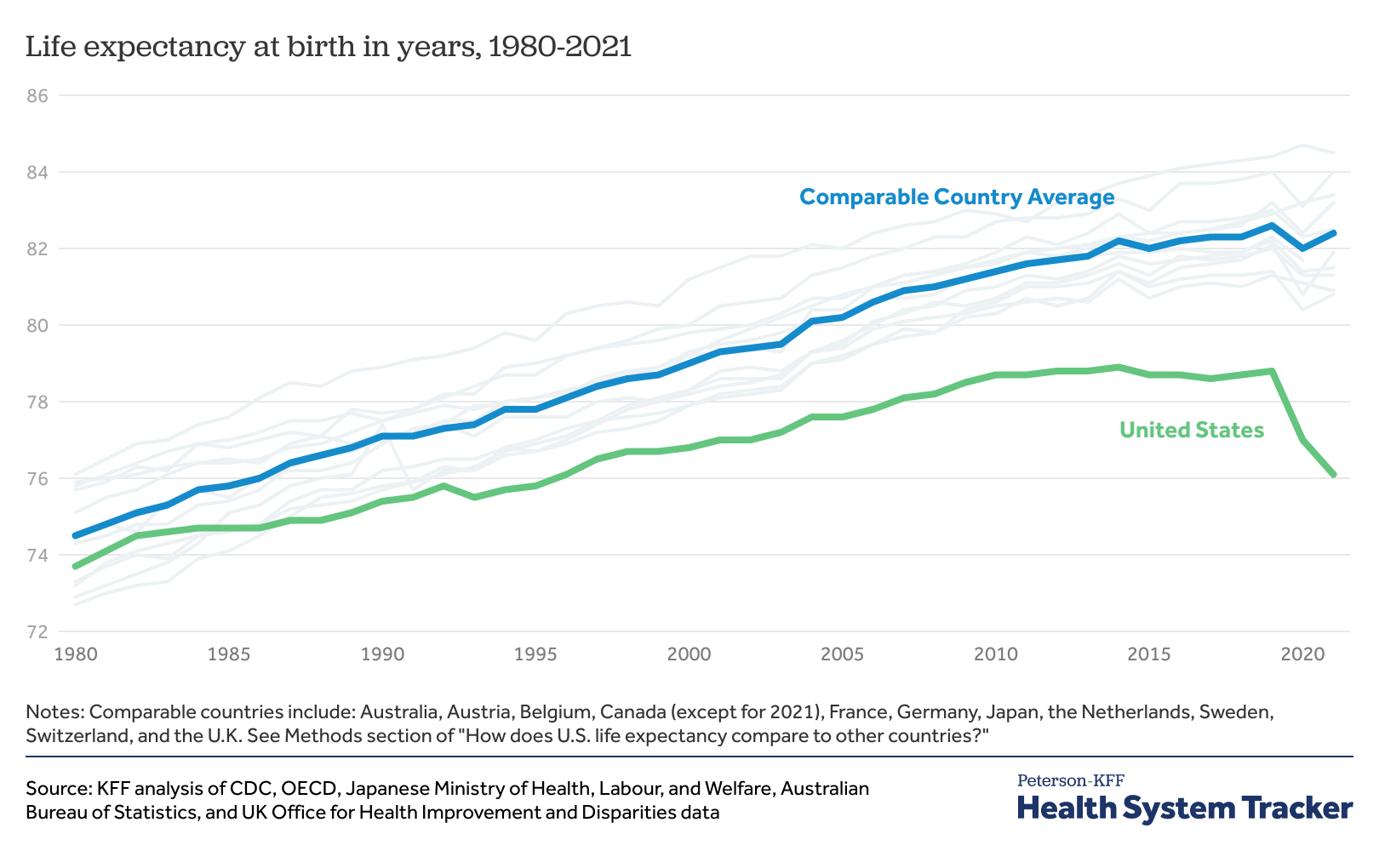

More than 40 countries sit ahead of the United States when it comes to their citizens’ life expectancy, by United Nations counts. Americans will live an average of 7.5 years less than people in countries with the highest life expectancy, despite being one of the wealthiest nations in the world and spending more than other countries on health care.

This shorter life expectancy is true across age brackets, racial demographics and income levels in the United States.

“There is something about being born in the U.S. that gives you a life expectancy disadvantage,” said Youssef Azami, a graduate student in public health and public policy at the University of Washington.

Yet Azami says the root causes of these poor health outcomes are not being acknowledged or addressed. While many people blame individual choices like diet and smoking, or limited access to affordable health care as the reason for poor health, research shows something different. University of Washington School of Public Health researchers Stephen Bezruchka and Azami point to upstream factors like income inequality, racism or social isolation as detrimental components to our health.

These social determinants of health have sweeping impacts on the entire population; even the wealthiest Americans can expect to live shorter lives than an average-income person in a peer country.

“There are many studies showing that even the healthiest among us are less healthy than ordinary people in other countries,” said Bezruchka, associate teaching professor emeritus of health systems and population health.

Azami recently conducted qualitative research for his thesis on what other graduate students studying public health and public policy believe is the reason for Americans’ poor health. From nearly a dozen interviews, students did not mention these social determinants of health as a primary role in life expectancy outcomes. Instead, students cited health care services as the biggest factor in determining health outcomes, followed by the influence of individual circumstances and personal behaviors on health. While some students mentioned the impact of poverty, it was always in relation to affording health care.

These findings are concerning, Azami said, because graduate students studying policy and public health will likely be the ones holding positions of power in government and health departments. They’ll be shaping policies — from the amount of taxes people pay to funding for early life — that will directly impact the health of populations.

“I would want graduate students to understand that these social and economic policies are the key factor in determining our population’s health,” Azami said. “So when we as professionals with graduate degrees are working in municipal, state and national governments, we are writing these tax policies, knowing how it’s going to affect the health of the population.”

While some schools of public health do emphasize these upstream social determinants of health in their curriculum, fighting core beliefs about agency over our health can be challenging. A 1997 study said that the ideas of social inequalities in health are not familiar topics to most lay people, who instead think individual factors play the most important role in their health. Bezruchka said it’s worth asking why people believe what they believe. In America, a huge emphasis is placed on personal choices, such as exercising, eating healthy foods, or seeing a doctor when someone is sick, he said. Many people believe it is their individual choices that have impact, far more than the system they live in.

These individual choices like diet, physical activity, and alcohol and drug use do play a role in health outcomes, however, it is the social and economic factors that influence how people can make these healthy choices. For example, Azami said that living in a food desert can lead people to have unhealthy diets, or residing in an unsafe neighborhood can discourage going outside to get exercise.

What causes shorter life expectancy?

Bezruchka himself once believed in the oversized impact of individual choices. He worked as an emergency room doctor for 30 years, and would make assumptions about how his patients’ choices like smoking were the biggest impact on their poor health.

Yet when he started exploring the health of different countries’ populations, he discovered that the country with the longest life expectancy — Japan — had two to three times more men smoking than the U.S.

Researchers studying health outcomes and life expectancy have surmised that there are many factors that could be at play when it comes to why U.S. life expectancy is so far below its peers. A pivotal report called "Shorter Lives, Poorer Health" looked into this very question. Published 10 years ago by the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the National Institutes of Health, researchers identified racial segregation, social isolation and child poverty, among other factors that led to poor health outcomes.

Bezruchka, who wrote Inequality Kills Us All, which shares research about how economic and social inequality leads to poorer health and higher mortality, found that research also points to factors like limited spending on early life, lack of social connections, and economic inequality as detrimental factors to the health of the entire U.S. population.

Early life

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life in particular have a huge impact on their health long term, Bezruchka said. Cells in a child’s body are rapidly dividing at a rate never experienced again in human life. In the International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, Bezruchka writes of some of the links between early life and adult health: Long-lasting negative health impacts can arise from as early as pregnancy. Stress during pregnancy has been linked to inflammatory markers in the offspring when they are in their 20s. Birth weight is linked to cognitive function in grade school, and weight at year one has been linked to coronary heart disease in adulthood. Family socioeconomic circumstances during childhood have impacts as those children enter adulthood.

Yet the U.S. spends very little money setting up children for success. The U.S. is one of only a few countries that don’t offer any paid family leave (the other countries without paid leave are the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea and Tonga).

“It can be definitively said that our peer nations investing in early childhood programs have better health outcomes, and if we had a national program, we’d be healthier,” Azami said.

Washington state is at least a leader in the U.S. in this front, with the state offering 12 weeks of paid parental leave. While this is still far less than its neighbor to the north, Canada, which offers at least partial ongoing income for a year, it’s a start, Bezruchka said. In total, 11 states have passed paid family and medical leave laws, but none greater than 12 weeks of paid leave: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington state, along with Washington, D.C.

“In a sense, you get what you pay for if you support early life,” Bezruchka said. “One of my students came up with the phrase, ‘Early life lasts a lifetime.’”

Lack of social connections

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has declared that the U.S. has a loneliness epidemic. In a 2023 report, Murthy shared many startling statistics about this epidemic, including that loneliness and social isolation are more harmful to one’s health than smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

One of the first studies to look at the impacts of loneliness on mortality was from 1979. Researchers studied thousands of residents in Alameda County, California, and found that people who lacked social and community ties were more likely to die than those with more extensive contacts. Since then, many other researchers have explored the linkage between loneliness and public health.

A 2010 meta analysis of 148 of these types of studies found that “the influence of social relationships on the risk of death are comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality such as smoking and alcohol consumption and exceed the influence of other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity,” the researchers wrote.

“What does a country do to improve social support? That’s the outstanding question,” Bezruchka said. “What should we do for people to have more friends to ask for help?”

Economic inequality

The U.S. once had the world’s longest lived population in the 1950s. During this time, there was much greater economic equality. But starting in the 1970s, wealth became much more concentrated in the upper rungs of the income ladder. This economic inequality has not been good for the health of any Americans, Azami said.

“The health of a population lies on a gradient and that gradient is impacted by a lot of factors; one of them is economic inequality,” Azami said. “Economic inequality causes stress and that impacts the health of everybody at every point in the gradient. And that causes a whole host of social problems.”

A dominant narrative in the U.S. is that economic inequality can be solved through education, which is often dubbed “the great equalizer.” But education does not drastically improve economic, health and life outcomes like people think it does, Bezruchka said. For example, maternal mortality rates do not improve depending on the education level of the parents.

“Unfortunately, if you take a college educated Black mother, her baby will have lower birth weight (below 5.5 pounds), than all the other racialized groups of any educational status,” Bezruchka. “In other words, trying to improve education as a way of avoiding the social determinants of health is especially problematic.”

Tax policies can be critical to helping reduce economic inequalities and encourage healthier societies, Azami said. He notes that future public health and public policy professionals play key roles in equitable distribution of the tax burden, such as higher tax rates for high income individuals and corporations, closing loopholes that allow for tax avoidance and implementing wealth taxes. These tax revenues can then be used to fund social welfare programs, education and infrastructure projects that benefit the whole population and lead to upward mobility, Azami said.

While the data points chronicling all the ways the U.S. lags behind other countries can be overwhelming, these are not irreversible outcomes. There are choices that can be made to improve the health of all Americans, Azami and Bezruchka said.

“These are all political choices we’ve made as a society,” Bezruchka said. “If people can realize that the choices they’re making are not allowing them to live longer, healthier lives, maybe they'd make different choices that would, in fact, be healthier choices.”

Learn more about inequality's impact on public health: