Fifty Years of Saving Lives, Serving the Public

UW School of Public Health marks half-century of impact

WRITTEN BY ASHLIE CHANDLER AND JEFF HODSON

Laying The Foundations

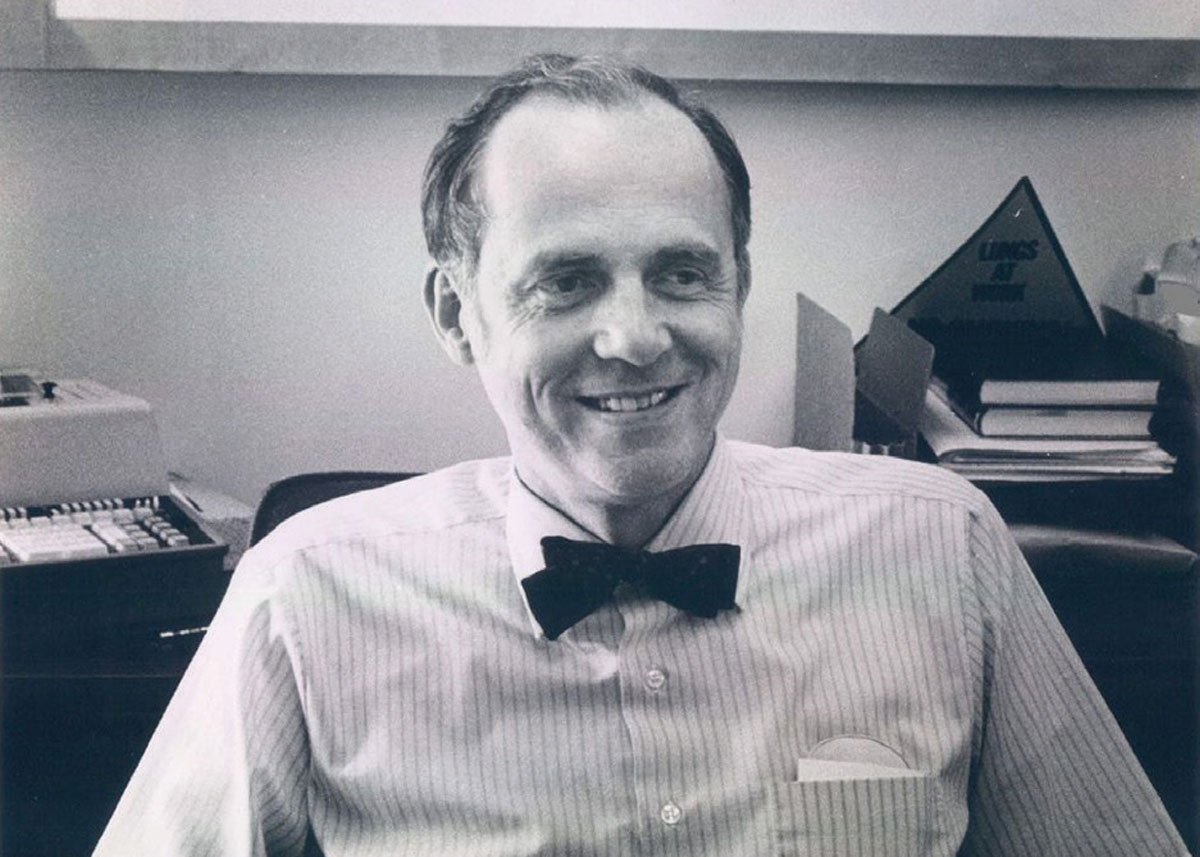

J. Thomas Grayston discovered his passion for public health on a Midwestern corn field. An old silo, to be precise.

It was there, in the 1950s, that Grayston, a young medical doctor at the University of Chicago, investigated a case of histoplasmosis — a lung infection caused by fungal spores. At the time, little was known about the disease.

Grayston had followed a patient back to his farm, 50 miles away in northwest Indiana. After inspecting the farm and taking soil samples, Grayston pieced it all together. The patient had become ill after cleaning out the old silo, disturbing soil containing infectious spores most likely from bird or bat droppings. The farmer’s children, who helped shovel and transport the soil, were also affected.

“Clinicians treat patients in hospitals but by going out into the community, learning where they lived and worked, we were able to find out how exactly the patient got infected,” said Grayston, now 96.

It was this experience that would launch Grayston into a career as an infectious disease epidemiologist, serving as one of the first members ever of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Epidemic Intelligence Service. He then led studies of infectious diseases in East Asia for a U.S. naval research unit based in Taiwan before taking on a new challenge at the University of Washington in 1960. The School of Medicine, which formed just after World War II, had a small Department of Preventive Medicine, which Grayston was asked to chair.

Grayston’s timing was good. Funds were available from the federal government for public health and infectious disease research and training, the UW allowed him to recruit more faculty and the state had new revenue to finance environmental health research. In 1963, the Environmental Health Laboratory, which opened more than a decade earlier and was housed in the Department of Preventive Medicine, received funding from the state to expand the lab facilities and boost efforts to improve occupational health for Washington’s workers.

By the end of the decade, the department had grown nearly tenfold, from four original faculty members. “Those 10 years, from 1960 to 1970, are really very important to the current school of public health,” Grayston said. “They really laid the foundation.”

Grayston’s early focus was on boosting research productivity and hiring key faculty who would become important leaders: Russ Alexander, Ed Perrin, George Kenny and Hjordis Foy, to name a few.

By 1968, the department was essentially set up as a school of public health. It had divisions that would soon become their own departments: biostatistics, epidemiology, pathobiology and environmental health (which began in 1947 as a small program in sanitary science). A health care studies program launched that year.

“As the department grew, it really didn’t fit in with the School of Medicine,” Grayston said. Its sheer size and specialties made it unique. Additionally, the Pacific Northwest needed a public health training and research center. “The nearest public health schools were in Berkeley and Minneapolis,” Grayston said.

Another motivating factor: federal funds for training were available specifically for schools of public health, of which the U.S. had only 11 at the time.

On May 22, 1970, the UW Board of Regents approved plans for an autonomous School of Public Health and Community Medicine, with Grayston as its first dean. A report on that meeting noted that the “emphasis on the health of population groups is ordinarily different from the emphasis on individual patient care characteristics of other departments of the School of Medicine."

Research was to focus on the causes of disease and preventive measures. The School was charged with mobilizing support for health-related legislation as well as reducing the cost and increasing the quality and availability of health services. The new School would continue to train medical students and provide PhD and master’s degrees for practitioners, teachers and investigators. It would also offer short courses for regional public health personnel. The School formally opened on July 1, 1970.

It already had a new home — the Health Sciences’ F-Wing — completed in 1966 with state and federal funding. Called the Preventive Medicine and Environmental Research Wing, it seemed like a lot of space at the time.

The UW School of Public Health and Community Medicine quickly became known as a strong research center, especially on respiratory infections and sexually transmitted diseases. “Our biostatistics group was seen as one of the better programs in the country,” Grayston said. “Same could be said for epidemiology.”

One major accomplishment included Grayston’s work with Palmer Beasley, James Gale and Roger Dietels in Taiwan, where the team successfully tested a vaccine for rubella.

While he laid the foundations for the School and its core disciplines, Grayston was dean for only one year. In 1971, John Hogness, former dean of medicine and then UW executive vice president, recruited Grayston to become vice president of health sciences, overseeing the six health sciences schools. Grayston maintained his research labs while an administrator and would return to his research until retiring in 2010. The man Grayston recruited to lead the new Department of Health Services, Robert “Bob” Day, would guide the School through its first decade, setting the tone for new collaborations and community outreach.

Timeline

1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s 2020s

Dean:

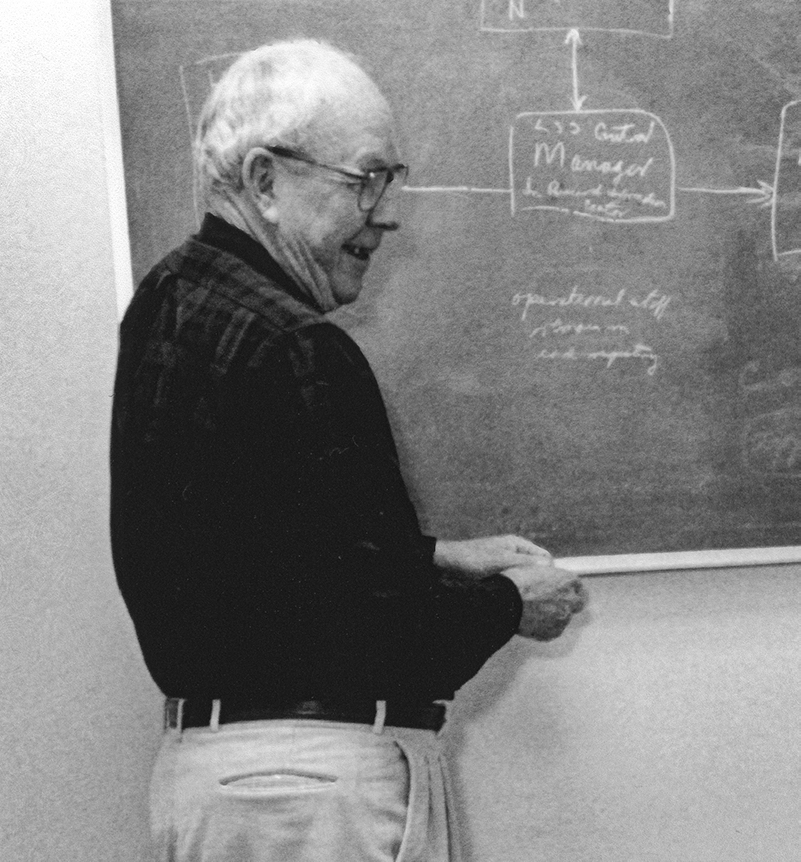

Robert Day (1972-1982)

Against a backdrop of the war in Vietnam, continued fight for women’s and racial equality and crusade to protect the environment, the UW School of Public Health and Community Medicine formalized its training of medical students along with a new generation of graduate students seeking to improve the health of human populations.

The School’s student body grew along with its thriving degree programs, such as the Master of Health Administration (MHA) program, headed for a time by William Richardson, then chair of the Department of Health Services, and Stephen Shortell, who was named Health Services chair in 1980. An Executive MHA Program was added in 1997 for working health care professionals. Also designed for working professionals was the Extended MPH Program (now called the Online MPH Program) that officially launched in 1980 to help practitioners advance their skills and knowledge in public health while based in communities across the country and internationally.

We had a good number of physicians in the program, including a female naval officer who was chief medical officer on one of the largest aircraft carriers in the fleet and a physician who was the chief medical officer for the entire U.S. Navy Pacific Command.

The School gained PhD programs in epidemiology (originally a PhD in preventive medicine) and biostatistics and master’s programs in epidemiology and health systems and policy. A new Northwest Center for Occupational Health and Safety, founded in 1977 and based in the Department of Environmental Health, provided financial support to graduate students in occupational health and safety and continuing education for practitioners in the field.

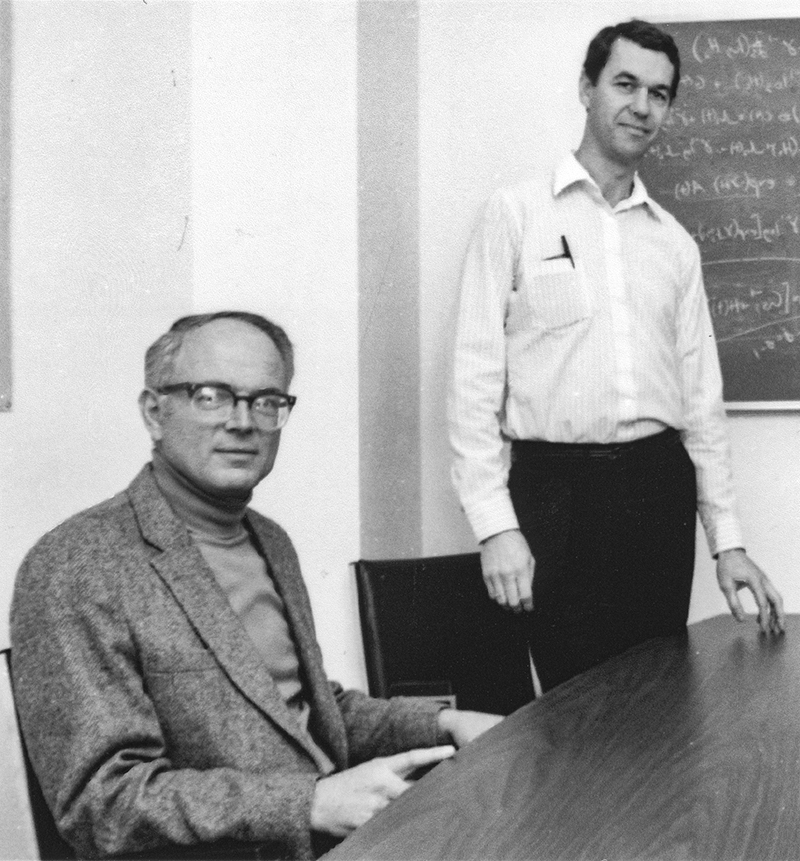

Under the leadership of Russ Alexander, the Department of Epidemiology expanded its expertise beyond infectious diseases to include genetic, injury, cardiovascular disease and cancer epidemiology. Donovan Thompson, chair of the Department of Biostatistics from 1973 to 1983, was integral to a flourishing collaboration between the School and the new Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. This partnership, championed by Bob Day, who would later become president of Fred Hutch, not only created synergy between the School’s epidemiologists and biostatisticians that led to important contributions in cancer research, but also allowed both organizations to attract high-caliber researchers like Ross Prentice, David Thomas and Janet Daling, a School alum, all who also would be key to educating the next generation of public health researchers.

Major scientific accomplishments included Palmer Beasley’s discovery that chronic infection with hepatitisB was a cause of liver cancer, a finding that led to interventions that have saved countless lives, and Noel Weiss’ studies linking the use of hormone therapy to ease symptoms of menopause to an increased risk of cancer of the lining of the uterus.

The School’s commitment to health equity began to take form during this decade. To improve access to quality health care in the U.S., particularly in rural communities, the MEDEX Northwest program, founded in 1969 by Richard Smith and housed in the Department of Health Services from 1972 to 1994, trained former military medics and corpsmen to be civilian health practitioners — laying the groundwork for the physician assistant profession. When Smith left the UW to expand this training globally in 1973, David Lawrence, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Clinical Scholar, took over and expanded the program to include nurses and others. By the 1980s, graduates could earn degrees in clinical health services. Additionally, in 1975, Paula Diehr led an influential evaluation of the Prepaid Health Care Project of Seattle’s Model Cities Program, intended to subsidize health care for the city’s low-income families. Bill Richardson, Doug Conrad and others in the Department of Health Services also took part.

The RWJF Clinical Scholars Program, awarded to the School in the mid-1970s, helped to boost the School’s training of young physicians as leaders and health services researchers, giving them the tools they needed to tackle complex health problems in communities. This program spawned some notable alumni and changemakers (see story) over the next few decades, such as pioneering gun violence researchers Frederick Rivara and Art Kellerman.

Dean:

Gilbert “Gil” Omenn (1982-1997)

Under the leadership of Gilbert “Gil” Omenn, originally recruited to be chair of the Department of Environmental Health, the School solidified its excellence in the basic sciences of public health and expanded to other fields such as health promotion and prevention, health policy and practice. Researchers continued to serve the state through their environmental health work and strengthened their collaborations with communities, health departments and other UW units.

Appointed as chair of the Department of Biostatistics in 1983, Norman Breslow, a world-renowned biostatistician, provided leadership that would guide the biostatistics department down a path to becoming the No. 1 biostatistics program in the world. He helped to build the modern field of biostatistics, nurturing the careers of young researchers and advancing science to improve public health. Breslow would lead the department for a decade.

The School expanded its training of students in the development and application of methods in epidemiologic research. Noel Weiss, who became chair of the Department of Epidemiology in 1984, and Tom Koepsell, who was handed the baton in 1994, established the School’s renowned two-course series on epidemiologic methods and co-taught it through 2011. The School also continued to broaden its epidemiological expertise by bringing back School alumni such as Bruce Psaty and David Siscovick, who co-founded the Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, and by partnering with Seattle-based institutions like UW Medicine and Swedish Medical Center to recruit clinical epidemiologists who could serve as mentors to students.

Major scientific accomplishments

Laura Koutsky, a PhD student who would later become a faculty member, conducted studies that demonstrated the link between human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. This research spurred the development of new cervical cancer screening methods and was critical to the first HPV vaccine trials. Koutsky served as the lead investigator in one of these trials.

Smallpox was eradicated due largely to the work of then-Affiliate Professor William Foege of the Department of Epidemiology and his novel surveillance and containment approach to vaccination.

Marilyn Bergner and Betty Gilson developed the Sickness Impact Profile, a novel tool for measuring health status behaviorally that attracts widespread use.

The Center of Excellence in Maternal and Child Health, founded by Irv Emanuel, admitted its first class of students in 1985. The program, now led by Daniel Enquobahrie, provides graduate-level training in maternal and child health research and practice and shares knowledge with the public health workforce through the Northwest Bulletin. The program, which was the first in the School to include a practicum as part of its training, has graduated more than 300 students. Fred Connell, Colleen Huebner and Melissa Schiff have also served as directors.

In 1986, the School was selected to house one of the first three Prevention Research Centers in the country, funded by the CDC. The School’s Health Promotion Research Center laid the groundwork for increased engagement with communities and a growing emphasis on public health practice. Recognizing the changing demographics at the time, the center — based in the health services department — was designed to focus on the health promotion of older adults. Later, in the 1990s, the center would develop a depression treatment program for older adults called the Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives, dubbed PEARLS, in collaboration with communities.

Reflecting the growing environmental justice movement, the School’s Department of Environmental Health, then led by Sheldon Murphy, recruited young faculty with excellent research potential and established the UW Superfund Research Program, with funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, to address human health and environmental issues related to hazardous substances. The program continues to partner with local, state, tribal and federal entities and impacted communities to understand and break the link between chemical exposure and disease.

Additionally, the environmental health department — together with the UW’s Department of Medicine and the Division of General Internal Medicine — established the Occupational and Environmental Medicine Clinic at Harborview Medical Center. The clinic continues to work with patients, labor unions, employers and community groups to prevent, diagnose and treat injuries and diseases caused or aggravated by work or community environmental exposures.

A small international health program began to form during this period, as Stephen Gloyd and others secured funding to lead projects with students in Mozambique and other parts of the African continent. To promote policies and programs that strengthen primary health care in Mozambique, Gloyd and a group of doctors and nurses created the Mozambique Health Committee in 1987. Over the next 30 years, the committee expanded its reach and mandate — becoming Health Alliance International — to implement health systems strengthening programs and research across four continents, and to provide a model for global health advocacy and intervention rooted in solidarity with public sector health systems.

In response to the AIDS epidemic in the U.S., the UW/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research was launched under the leadership of King Holmes, becoming one of the first and largest centers of its kind in the country. The center has since contributed to improving the continuum of care for individuals with HIV around the world. Locally, a strong partnership with the public health department helped Seattle and King County become the nation’s first major metropolitan region to achieve the World Health Organization’s 90-90-90 goal.

In 1988, Joan Kreiss established the International AIDS Research and Teaching Program at the UW, with funding from the Fogarty International Center, to foster international collaborative AIDS research through scientist exchange. The program has since trained more than 330 investigators in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and many former students have continued collaborative research relationships with UW colleagues after they returned to their home countries. The program is now led by Carey Farquhar.

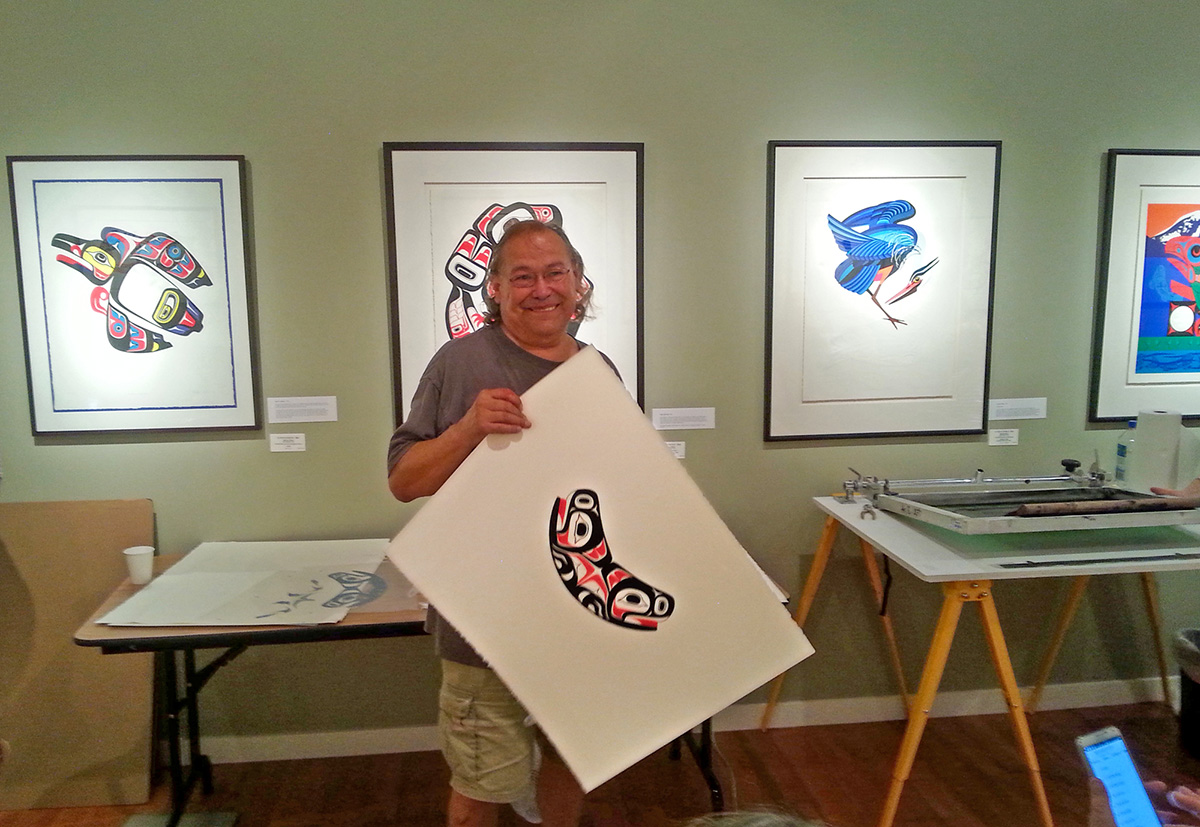

1981

Marvin Oliver, who passed away in 2019, designed the Soul Catcher as a logo for the School. It’s a Northwest Native American symbol for physical and spiritual well-being.

1982

The UW offered its first undergraduate course in toxicology.

Dean:

Gilbert “Gil” Omenn (1982-1997)

An era of continued maturity for the School, this decade saw many key accomplishments that helped to establish the institution as a national leader in public health research, training and practice. The School embraced pivotal philanthropic partnerships and later in the decade gained Patricia “Pat” Wahl as the first woman to serve as dean.

To mark the 25th anniversary of the School in 1995, the Department of Biostatistics, led at the time by Thomas Fleming, hosted the first Seattle Symposium in Biostatistics, attended by more than 400 statisticians from over a dozen countries.

In the Department of Health Services, researchers partnered with Group Health Research Institute to conduct the “Kaiser Evaluation” of interventions to promote community health. Susan Hedrick and others developed a way to evaluate the effectiveness of adult day health care programs for veterans. Donald Patrick, who was hired in 1987 to launch the Social and Behavioral Sciences program, co-authored a world-famous report on health status and quality of life. Paula Diehr, who served as interim chair of the department in 1994, and Fred Connell, a long-time associate dean of academic affairs, won AcademyHealth’s Publication-of-the-Year Award for their paper on the null hypothesis in a small-area analysis.

Several centers launched during this period that reflected the strong, cross-disciplinary partnerships of the time and the coming of age of the School’s expertise.

- David Eaton founded the Center for Ecogenetics and Environmental Health (now called the Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment, or EDGE).

- Elaine Faustman created the Institute for Risk Analysis and Risk Communication.

- Mark Oberle founded the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice to help improve public health through collaboration between academia and the practice field.

- Richard Fenske and Matthew Keifer established the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center to address health and safety concerns in the farming, fishing and forestry workforces.

The Department of Environmental Health graduated its first PhD students in 1995 and an innovative graduate training program in public health genetics was established in 1999. Led by Melissa Austin, a faculty member in the epidemiology department, the public health genetics program focused on using genomic advances to improve population health. The Institute for Public Health Genetics, as it is known now, remains the only one if its kind in the world, offering a PhD, MPH and graduate certificate in public health genetics as well as an MS in genetic epidemiology. Bruce Weir currently serves as director.

Early in the decade, the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Nutritional Sciences, which included a PhD program in nutritional sciences, moved into the School, with an administrative home in the Department of Epidemiology. (The Nutritional Sciences Program, as it is now known, would later move into the Office of the Dean). Elaine Monsen served as director of the program from 1994 to 1998, at which point Adam Drewnowski took the helm. An MPH in nutrition was created in 1996.

In 1993, Michelle Williams, then a professor of epidemiology, created the Minority International Research Training Program, which trained students from underrepresented backgrounds for research and leadership careers in public health. The program trained hundreds of students in global health, biostatistics and epidemiology in over 14 international research sites in South America, Southeast Asia, Africa and Europe. Williams is now dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In 1995, the Department of Environmental Health was authorized by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to offer health and safety training and continuing education courses through the Pacific Northwest OSHA Education Center, serving Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Alaska.

The Health Policy Analysis Program, a service team that worked with state policy makers on issues of public health importance, made some significant headway. Led by Aaron Katz from 1988 to 2003, the program staffed a state commission for two years to come up with a health care reform proposal, which was passed by the state legislature in 1993. Though the bill was repealed two years later, parts of the reforms were kept in place.

The Public Health Genetics program was one of the signal initiatives of this time. It was a splendid example of engaging all the other UW Health Sciences schools, the Law school, public policy, anthropology and other parts of the Campus.

Boosted by faculty who held prominent positions in local health districts, such as James Gale, former Wenatchee health officer, the School continued to build ties with practice partners in the state and strengthened its status as a practice-oriented school of public health.

Making philanthropy a priority, Omenn cultivated strategic relationships with private organizations that led to endowments that have continued to support the recruitment of promising researchers and educators as professors and chairs (learn more about Omenn’s philanthropic legacy).

Dean:

Patricia “Pat” Wahl (1999-2010)

Under Pat Wahl, a professor of biostatistics and an early graduate of the School, the School changed its name to the School of Public Health. It took critical steps to expand its impact on global health and nutritional sciences and began to build a pathway for undergraduates to study public health.

Together with the UW School of Medicine, the School launched a new Department of Global Health in 2007 with a generous investment from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and initial funding from Washington state, and named King Holmes the founding chair. The School’s former Department of Pathobiology became a PhD program within the new department and an MPH program was launched in 2008.

Four centers formed the new global health department: The Center for AIDS Research, Health Alliance International, Global Health Resource Center and International Training & Education Center for Health (I-TECH). I-TECH was established by Ann Downer in 2002 to develop a skilled health workforce and strengthen health systems globally. Since its inception, I-TECH has supported programs in more than 30 countries, launched several local health organizations to ensure country ownership and transitioned more than 350 programs to local entities. Pamela Collins became I-TECH's executive director following Downer’s retirement in 2020.

In 2008, the global health department’s International Clinical Research Center (ICRC) was established to coordinate and implement multi-center international infectious disease prevention trials. ICRC has since spearheaded pivotal HIV prevention research, including the Partners PrEP Study, led by Jared Baeten and others, which contributed to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval in 2012 of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention. Today, the ICRC is home to several studies on the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Bruce Weir, who was recruited to lead the Department of Biostatistics in 2006, brought the Summer Institute in Statistical Genetics to the UW School of Public health. The institute would eventually expand to include Statistics in Modeling & Infectious Diseases, Statistics in Clinical & Epidemiological Research and Statistics in Big Data. Weir still serves as the institute’s director. He was also integral in the creation of the Genetic Analysis Center in 2007 to advance the discovery of genetic variation and how it contributes to human disease and well-being. The center, which Weir now directs, is the coordinating center for the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Under Chair David Kalman, the Department of Environmental Health changed its name to the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences to reflect its growing expertise and service in occupational health and safety. In 2005, the Environmental Protection Agency awarded its largest-ever research grant to the department to study the connection between air pollution and cardiovascular disease.

This period was also defined by key achievements made to build up a thriving program in nutritional sciences and dietetics, led by Adam Drewnowski. Early in the decade, the Center for Public Health Nutrition was created and an MS in nutritional sciences was launched. In 2008, two successful and accredited programs – the Didactic Program in Dietetics and the Dietetic Internship – were combined to create the Graduate Coordinated Program in Dietetics, led by Director Anne Lund. The School also developed more undergraduate courses in nutrition.

The School launched a new PhD program in health services in 2000, along with an occupational health services research training track, jointly sponsored by the Departments of Health Services and Environmental Health. A bachelor’s program in Health Informatics & Health Information Management (HIHIM) began in 2001, and a master’s degree option in HIHIM would be added in 2012. The School also launched an innovative MPH program in 2002, called Community-Oriented Public Health Practice (COPHP) program, which uses a problem-based learning approach to train students eager to develop practice skills. Fred Connell was the program’s founding director. Bud Nicola, who helped design the program, took over later in the decade and Peter House would guide the program into the next decade. Amy Hagopian served as the program’s director from 2013 to 2021.

Pat Wahl established a public health practice pathway for faculty promotion and created the first associate dean position for public health practice, held by Mark Oberle, a model followed by many other schools since. Together with Oberle, Wahl visited 33 local health departments to improve relations with the School’s practice partners.

Deans:

Howard “Howie” Frumkin (2010-2016)

Joel Kaufman (2016-2018)

Howard “Howie” Frumkin worked to create a sense of the School as a whole rather than the sum of its parts and set the School on a path toward addressing important and emerging public health challenges, from climate change to obesity. When Frumkin departed in 2016, Joel Kaufman, a long-time faculty member, was selected to serve as interim dean and was integral to reshaping the School’s popular MPH program and to jump-starting its efforts around equity, diversity and inclusion. Hilary Godwin was recruited to become dean in 2018.

Building off the School’s 2012-2020 strategic plan, spearheaded by Howie Frumkin, the Center for Health and the Global Environment (CHanGE) was formed in 2014 and Kristie Ebi was hired as its first director. The center, which is shared between the Departments of Global Health and Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences, brings together an interdisciplinary team of researchers and practitioners to partner with communities to develop tools, test interventions, implement solutions and train the next generation to promote and protect health in a changing climate. Jeremy Hess took over as director in 2019.

Other strategic hires during this period included Alison Fohner, a genetic epidemiologist and a 2015 graduate of the School’s PhD program in public health genetics; Anjum Hajat, who studies social and environmental stressors and how they impact health; Jessica Jones-Smith, who studies the social, environmental and economic causes and correlates of obesity risk; and Bryan Weiner, who would lead the Department of Global Health’s new Implementation Science Program.

The Department of Global Health continued to flourish on many fronts. A PhD program in Global Health Metrics and Implementation Science was created and the Global Health E-Learning Initiative began to offer online courses and educational resources to support students, faculty and health workers worldwide. Since 2012, these courses have enrolled more than 50,000 students from 59 countries. The department also gained the Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents and Children (Global WACh) — now directed by Grace John-Stewart — that takes a life-cycle approach to scientific innovation and leadership. Additionally, the Program on Global Mental Health began with the goal of expanding access to effective mental health interventions. The program is led by Pamela Collins and is a joint effort between the Departments of Global Health and of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. In 2014, Judith Wasserheit became chair of the department and the first woman chair in the School.

The UW's 25-year Population Health Initiative kicked off in 2016, bringing together disciplines across the University to work on solutions to local and global population health issues. To bring key partners in the initiative under one roof, the UW broke ground on the new Hans Rosling Center for Population Health, which officially opened in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The building was funded in large part by a transformative gift from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and now serves as the School’s new home.

In 2018, the Seattle City Council unanimously passed regulation requiring gun owners to safely store their firearms and to report stolen guns, a policy significantly informed by the School’s researchers, including Ali Rowhani-Rahbar and Frederick Rivara. Earlier that same year, a study led by then-PhD student Erin Morgan showed that only 37% of Washington state’s gun owners safely store their firearms. Later, in 2020, the UW received $1.5 million from the CDC to study handgun carrying among rural adolescents. That study is led by Rowhani-Rahbar, who was named the UW’s Bartley Dobb Professor for the Study and Prevention of Violence during this period and also co-directs the Firearm Injury & Policy Research Program at Harborview Injury Prevention & Research Center.

Other centers that formed

2013: The Center for One Health Research was created to investigate the links between people, animals and the environment we share.

2013: The Seattle-Denver Center for Innovation was established to conduct health services research that advances veteran-centered and value-driven health care. The center is a partnership between the Health Services Research & Development programs at Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound in Seattle and VA Eastern Colorado in Denver.

2017: The Center for Health Innovation and Policy Science was founded to improve health across communities and the lifespan through innovation, evaluation and training in health policy and health systems science.

The Strategic Analysis, Research & Training (START) Program was established in 2011 under the direction of Judd Walson and Lisa Manhart. The program was a collaboration between the School’s Department of Global Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to provide high-quality research support to help meet the Foundation’s strategic information needs. In 2014, it expanded into the START Center and has continued to provide original research to global and domestic health teams.

Janet Baseman, a School alum turned faculty member, founded the Student Epidemic Action Leaders (SEAL) Team in 2015 to provide students across the School with experience in applied epidemiology through methods training and field assignments at state and local health departments. Since the program began, students have offered more than 2,200 hours of support for assignments ranging from outbreak investigation to emergency response. In April 2020, members of the SEAL Team were called to participate in Washington state’s surge response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The School adopted an anti-racism curriculum competency for students that was developed by Amy Hagopian, Kate West, Clarence Spigner and India Ornelas, who chaired a School-wide Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Committee during this time. In 2018, the School hired its first-ever director of EDI, Victoria Gardner, who is now an assistant dean. Over the last few years, Gardner has led a tremendous effort to create an EDI road map for the School and to launch universal anti-racism training, among other initiatives (learn more about the School’s EDI efforts).

A popular individualized studies degree in public health moved from the UW College of Arts & Sciences into the School of Public Health in 2012, and the curriculum was revised to create the Public Health Major. Sara Mackenzie was appointed to oversee the program and staffers Tory Brundage and Susan Inman were hired to advise students and manage the major. In 2018, the major was renamed the Public Health-Global Health Major to better reflect its domestic and global competencies. The program now offers both a BA and BS, and it has grown to admit 300 students every academic year. More the 40% of students in the program have self-identified as first-generation college students. Barbara Baquero currently serves as the program’s interim director.

Continued growth in undergraduate programs

2013: A minor in nutrition is offered at the UW.

2012: A suite of undergraduate courses is established in the Institute for Public Health Genetics.

2018: A new undergraduate major in Food Systems, Nutrition and Health was launched.

Jennifer Otten, one of the driving forces behind the School’s Food Systems, Nutrition and Health major, took on an added role as Food Systems Director and the study of food systems became a new focus for the Nutritional Sciences Program.

Under Joel Kaufman, the School embarked on an ambitious journey in 2018 to reshape its popular MPH program with a new common core curriculum that integrates research and practice skills while preparing students for an ever-changing public health landscape. The re-envisioned MPH program launched in the fall of 2020 and is led by Director India Ornelas and instructor teams for each of the six courses now required by all MPH degree students (except those in COPHP).

The School welcomed its first cohort for the Master of Science Capstone in Biostatistics, designed for students who wish to enter the job market upon graduation. In 2019, Lurdes Inoue became the first woman to chair the Department of Biostatistics.

Major scientific accomplishments

2011: Former Biostatistics Chair Thomas Fleming published landmark research in the New England Journal of Medicine on the prevention of transmission of HIV.

2013: In a collaboration across departments in the School and with three other universities, Amy Hagopian and Abraham Flaxman conducted a household survey across 100 geographic clusters in Iraq to estimate mortality associated with the 2003 invasion.

2016: Joel Kaufman, who served as interim dean during this period, and his collaborators publish a decade-long study that showed people in the U.S. living in areas with more air pollution accumulate deposits in the arteries that supply the heart faster than do people living in less polluted areas.

2019: An interactive mapping tool was created to rank Washington state communities most hurt by environmental health risks. State policymakers are now using the tool to inform the state’s transition to 100% clean energy by 2045. Then-PhD student Esther Min, Edmund Seto and Michael Yost, who was named chair of the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences in 2014, developed the tool alongside community partners.

2019: A study funded by the Washington State Legislature found that communities underneath and downwind of jets landing at Sea-Tac International Airport are exposed to a type of ultrafine air pollution distinctly associated with aircraft.

Dean:

Hilary Godwin (2018-Present)

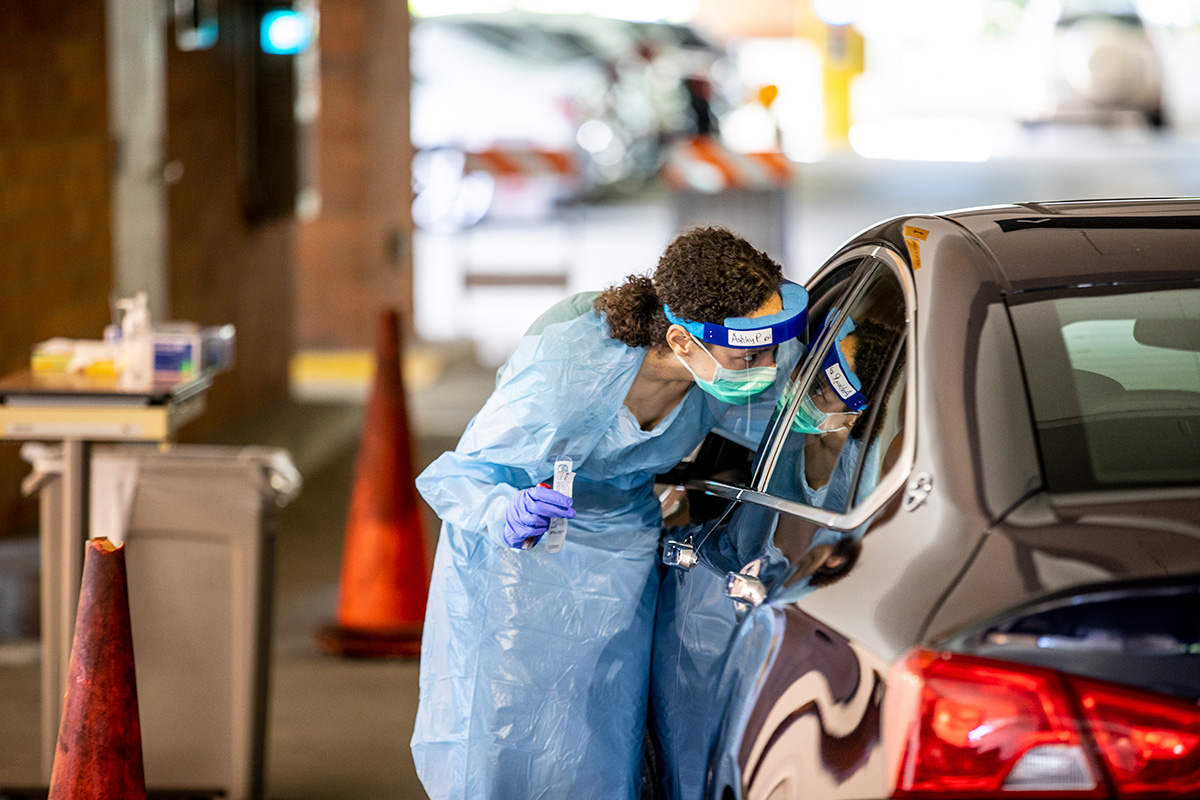

2020 was meant to be a year of celebration, as the UW School of Public Health was due to turn 50 on July 1. Instead, Hilary Godwin led faculty, staff and students through an unprecedented year of major, world-shifting events, including a new movement against systemic racism, the burning of wildlands in the west, a tempestuous presidential election and the worst pandemic the world has seen in more than a century. Dean Godwin has continued to bring renewed commitment to operating the School in a manner that reflects its public health values.

On Feb. 19, hundreds of people from across the UW’s health sciences schools gathered in a lecture hall on the University’s Seattle campus to discuss a newly named coronavirus disease, COVID-19, that was spreading around the world and had just been identified in Washington state. In a sobering moment toward the end of the event, Scott Dowell from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation asked the audience who believed the virus would have such an impact in Seattle that the intensive care units (ICUs) would fill up with patients. Only a handful of attendees raised their hands.

Just three weeks after that event, which was hosted by the UW’s MetaCenter for Pandemic Disease Preparedness and Global Health Security (now the Alliance for Pandemic Preparedness), the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Within months, hospital ICUs in Seattle and in other cities around the world were filled with record numbers of critically ill patients.

Under the leadership of Hilary Godwin, the School became one of the first in the country to move all its courses online on March 9 to help curb the spread of COVID-19. The UW made Zoom, a video conferencing tool, available to all current faculty, staff and students. Teaching faculty and assistants translated their coursework to better fit the new, remote environment. They also redesigned experiential-learning opportunities for students such as capstones and clinical rotations. Students worked with local public health agencies to track the disease while faculty and staff pivoted to conduct rapid research, several of which were awarded grants from the UW’s Population Health Initiative.

The School began a series of weekly webinars in March to share the latest updates on the School’s and the UW’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The School has since hosted about three dozen webinars that have contributed to a greater sense of community as faculty, staff and students adapted to remote life.

On May 25, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, Minnesota, after being handcuffed and pinned to the ground by a police officer’s knee, kicking off a series of protests against police violence. Countless people across the U.S. and around the world demonstrated and called for racial justice. In Seattle, faculty, staff and students joined thousands of doctors, nurses, health care workers and other public health experts to demand an end to systemic racism.

More than 300 students, staff and faculty signed a petition calling for mandatory, recurring anti-racism training for all students and employees in the School. Dean Godwin tasked the School’s EDI Committee and a dedicated workgroup with developing and implementing the universal anti-racism training, which began rolling out in the fall of 2020 (visit story to learn more).

More than 700 students graduated in June in the School’s first-ever virtual graduation celebration and a new, five-year strategic plan launched in July. The 2020-2025 plan centers on a commitment to making public health impact and has equity, justice and anti-racism as a through line. Jared Baeten, who served as vice dean of strategy, faculty affairs and new initiatives from 2019-2020, was vital to the development of the strategic plan. He also led the development of the School’s new faculty compensation plan (learn more about Baeten’s next chapter).