WRITTEN BY ALLEGRA ABRAMO AND ASHLIE CHANDLER

ILLUSTRATIONS BY TED BOYER

As COVID-19 began spreading across Washington communities, Janet Baseman, associate dean for public health practice at the UW School of Public Health, sent an urgent email with a survey to everyone in the School.

“Are you able to help? What are your skills? Are you available to work on site?” were among the questions Baseman asked. Around 700 responses poured in from faculty, staff and students.

That enthusiasm is evident in the unprecedented response to the pandemic by academic public health professionals across the School.

Faculty and students have bolstered the beleaguered public health workforce by training and deploying contact tracers. They are providing public health departments with timely research on everything from infections in nursing homes and the public’s adoption of masks to the pandemic’s impacts on immigrant communities. They’re supporting the development of vaccines, treatments and technologies to combat the virus. And they serve as trusted experts who translate the science for the public, journalists and government leaders.

“One of the big benefits to working with the School of Public Health,” said former Washington State Health Officer Kathy Lofy, “is that they not only help us implement new things, but they study it at the same time, which gives us more information about the effectiveness.”

Designing innovations for public health practice

One of those ‘new things’ might be on your cell phone right now.

In collaboration with UW faculty from Schools of Public Health, Medicine and Computer Science, the Washington State Department of Health launched an exposure notification phone application last November. Called WA Notify, it uses phones’ Bluetooth signals to exchange anonymous codes with other nearby phones running the app. Users can then receive notifications — in 29 languages — when someone they have been in close contact with in the previous two weeks tests positive for COVID-19. The app, which uses a platform developed by Google and Apple, doesn’t share when, where or by whom you were exposed.

“To me, it’s kind of empowering,” said Baseman, who chaired a diverse group of stakeholders advising the Department of Health on WA Notify and oversaw a test run at the UW. “I really love the idea of having a tool that doesn’t ID back to me personally, where I can do good for others if I test positive by letting them know they were exposed,” she said. “And likewise, I get the benefit if somebody that I’ve been in close contact with tests positive.”

Traditional contact tracing has a number of limitations, including that people often don’t know or can’t remember everyone they’ve been in contact with in the last 14 days. It’s also extremely resource intensive, and health departments at times have found themselves unable to keep up with the volume of cases.

“This technology is a privacy-preserving way to fill in some of those gaps,” said Baseman, also a professor of epidemiology and adjunct professor of health services at the School. As of April 2021, 1.9 million users downloaded the WA Notify app, representing 25% of the Washington state population. Baseman and her colleagues will continue working with the Department of Health to evaluate the app, including whether it benefits communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Serving communities most in need

Local health departments and government entities have also turned to the School for help collecting and analyzing information they can use to better target resources or communicate with communities most in need.

India Ornelas, associate professor of health services, consulted with Public Health – Seattle & King County to understand the impacts of COVID-19 on Latina immigrants in the county. Surveying women who had participated in a program called Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA) to reduce stress, anxiety and depression, Ornelas found the pandemic had taken a big toll on their economic well-being.

"Our role is to help to translate the science and the huge amount of information that’s coming out into actionable information."

Nearly 40% of survey respondents said their work hours had been cut and 28% were not working at all. Seventy-two percent of respondents expressed concerns about obtaining food and 75% expressed concerns about paying for housing. The women also reported finding the online ALMA sessions valuable during the pandemic. Results of the survey were shared with the local public health department and the King County Latinx Community Response Team.

“A lot of these women are already living in precarious positions… and are at increased risk of poor mental health,” Ornelas said. “So it’s really important to figure out if there are ways we can reach out to them.”

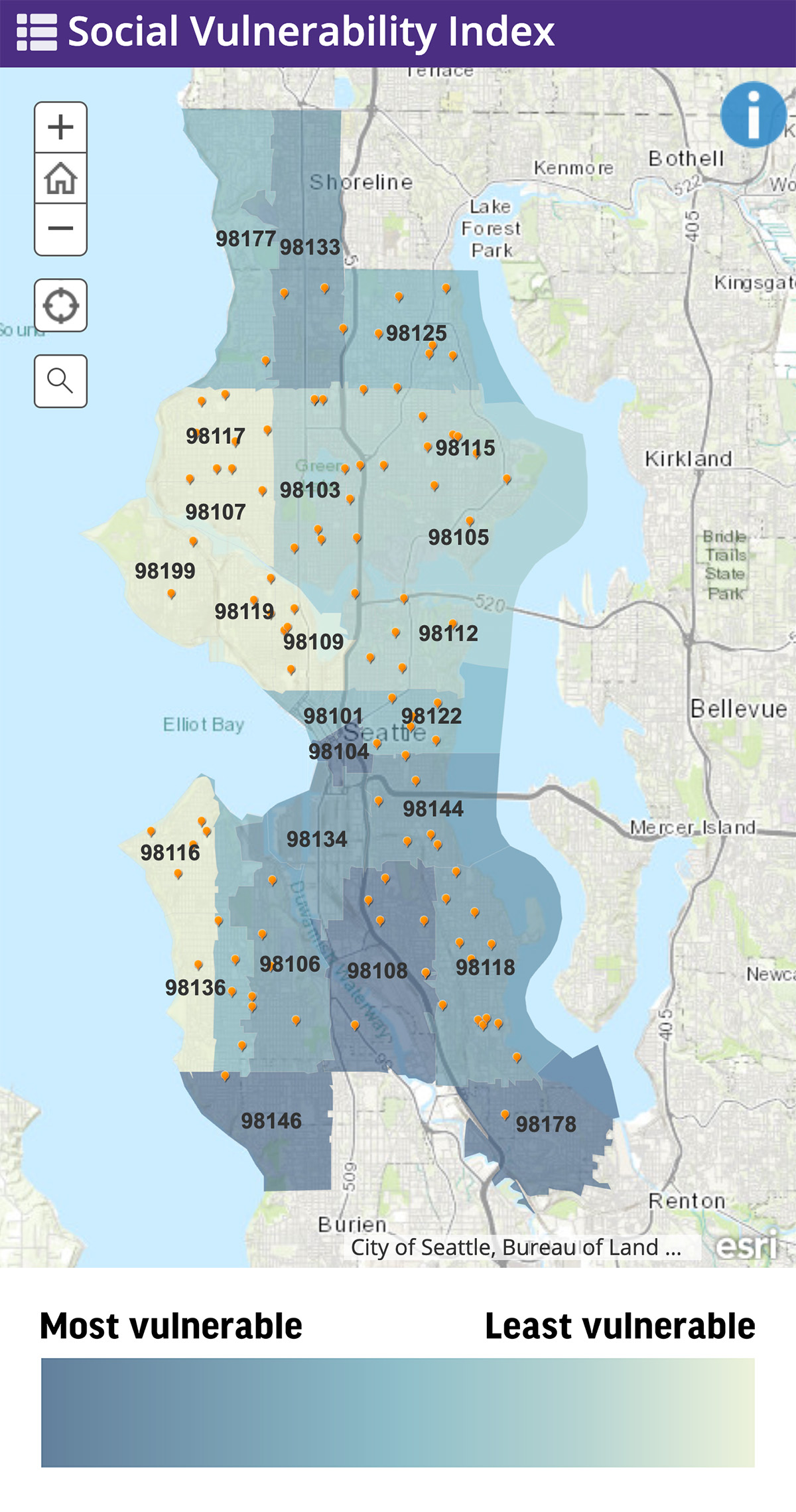

Other researchers at the School, this time in the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), developed a mapping tool for the City of Seattle to use to increase vaccine access and equity for the most vulnerable communities. The tool lets city officials and others compare, by ZIP code and census tract, COVID-19 case rates with social vulnerability conditions, such as high poverty, crowded households and limited vehicle access.

“The tool shows a pattern,” said Esther Min, an alumna who led the project as a research consultant for DEOHS. “Communities that have experienced high COVID-19 outcomes have high social vulnerability.”

The mapping tool, which was developed with Edmund Seto, associate professor of DEOHS, has helped the city decide where to place mobile and pop-up vaccine clinics as well as mass vaccination sites. Min said it could also inform when and where to mobilize vaccination events with local community leaders.

Communities that are disproportionately impacted by climate change and other health and environmental issues “are always hit first and worst,” said Min. “When health departments and decision-makers think about vaccine access and equity, it’s important to consider prioritizing frontline communities who often bear a greater burden.”

Making sense of the science

COVID-19 has generated an unprecedented volume of research of varying quality. Without the time or skills to assess the quality of scientific evidence, the general public is vulnerable to misinformation about the disease. And already-overstretched public health workers needed help to stay on top of the constantly evolving science.

That’s why the Washington State Department of Health in May 2020 funded a UW team led by Brandon Guthrie, assistant professor of global health and epidemiology, and Jennifer Ross, acting assistant professor of global health and medicine, to help sort the wheat from the chaff.

A rotating crew of five graduate students and four faculty screen roughly 400 articles a day, winnowing those down to the most relevant 10–15 to summarize as part of a daily COVID-19 Literature Situation Report. More than 5,600 people subscribe to the report, which is written to be useful to public health professionals but accessible to the general public.

“Our role is to help to translate the science and the huge amount of information that’s coming out into actionable information,” Guthrie said.

The Department of Health’s Lofy called the literature reports “incredibly valuable.” She and others leading the state’s COVID-19 response read it every day, she said.

Communicating in a crisis

Public health academics are used to talking to each other about research, but they also have to be ready to communicate with a range of non-experts, especially in a pandemic.

That’s one of their most important roles, said Dean Hilary Godwin, who has testified before Congress, sits on Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan’s COVID-19 Task Force and regularly presents to business and civic leaders.

“My goal is to reinforce the messaging or priorities that have been put forward by public health agencies,” Godwin said, “and to make sure that people understand the public health concepts that went into those decisions they’re putting out.”

Nicole Errett, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences, also made communicating about the pandemic one of her priorities. A disaster and public health policy researcher, Errett was fielding dozens of media requests at the beginning of the pandemic because she knew how important it was to ensure accurate messages were getting out to the public.

“During an emergency, the public needs clear and consistent messaging that acknowledges that conditions and information will evolve, and guidance may change,” Errett said. “If public health experts don’t provide that information, someone else will fill the void. And the information that a non-expert may provide runs the risk of being inaccurate or inconsistent with response goals.”

That could lead to misinformation, and even disinformation, and it could also erode the public’s trust, she added.

For some faculty, being thrust into the role of public communicators has been eye-opening. Marissa Baker, who is regularly quoted in the local and national media on the pandemic’s impact on workers, said this experience has reinforced for her the important role that industrial hygienists play in keeping workers — and the public they interact with — safe and healthy.

“Occupational health isn’t often on the front page of the newspaper,” said Baker, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences. “Interest from the media and general public in what I do has made me optimistic that there will continue to be a focus on the health of workers even as we get past the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Associate Dean Baseman said the pandemic has reinforced the need for schools of public health to better prepare both students and faculty to communicate effectively with the public, media and politicians.

“Especially in a time like we are in now, where politicization of these foundational public health measures is so extreme,” she said, “it makes the voice of experts like us, who work in the field of public health, even more important.”